Discover more from Back Row

The Truth About Real Fur, Faux Fur, and Sustainability

A new fur ban is in effect in California, reviving the decades-old talking point that faux fur is "less sustainable." But that claim is misleading.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. Today’s issue is free to read and features the kind of story that would be difficult if not impossible to run in a publication monetized by brands with ad budgets. If you want to support more journalism like this, the best way to do so is by becoming a paid subscriber. For $5 a month or $50 annually (which saves you $10 per year), paid subscribers get around two Back Row posts a week, plus access to commenting and the complete archive.

If you’re not ready to pay right now, you can also support this newsletter by sharing it on social media, tapping the heart up top, and forwarding it to friends.

As of January 1, the sale of new fur products became illegal in California. This ban, which passed in 2019 but just went into effect, is the first state-wide ban we’ve seen of the material, and it seems reasonable to expect similar legislation to follow, both in the U.S. and abroad.

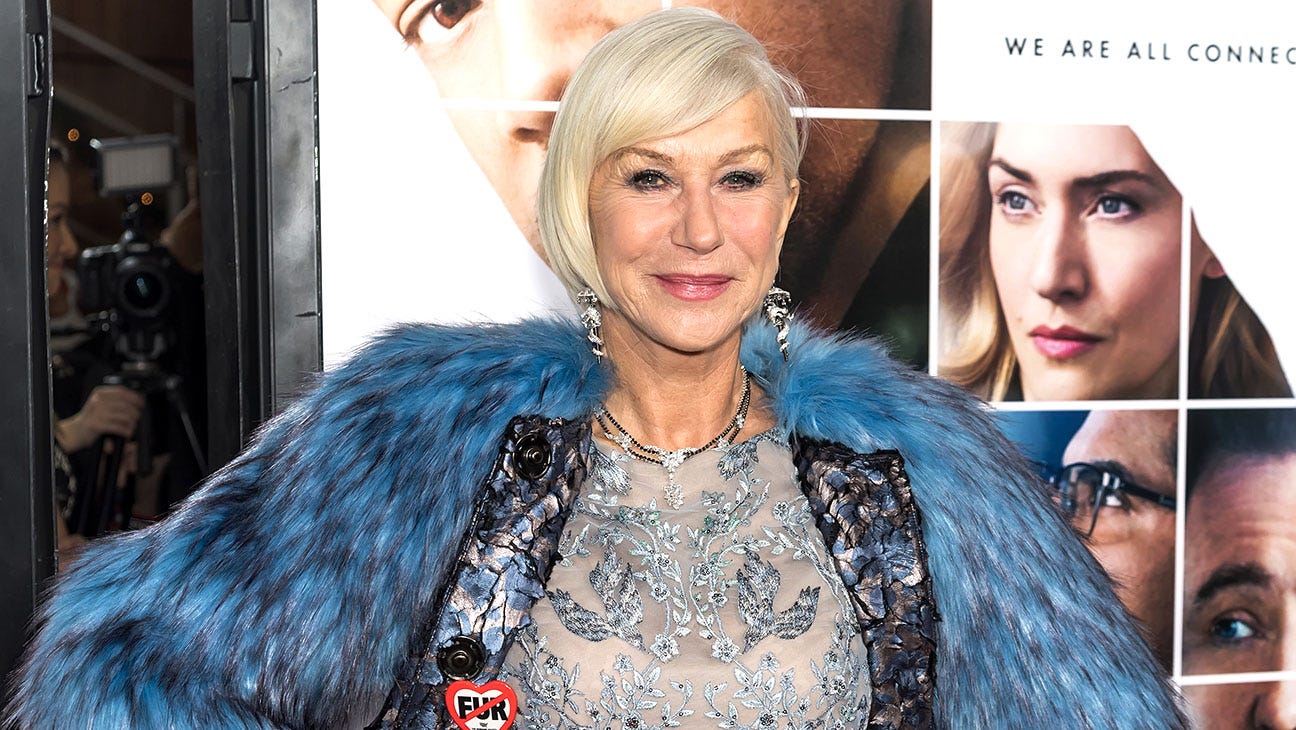

I posted about the ban on TikTok and Instagram (which is where I like to throw up news bites I don’t plan to cover in Back Row) and the instantaneous reaction from many commenters was the claim that real fur is “more sustainable” than fake fur. This idea that real fur is better for the environment has been a fur industry talking point for many years and has been surprisingly effective, trickling all the way up to longtime fur defender Anna Wintour (though, as I exclusively report in my biography about her, she quietly switched to faux fur in recent years). In a 2019 CNN interview with Christiane Amanpour, she said, “Fake fur is obviously more of a polluter than real fur.”

But fashion sustainability experts agree that this isn’t obvious. Moreover, asking if real or faux fur is “more sustainable” is simply a bad way to look at this issue.

Fashion sustainability experts say that slaughtering animals for fashion and “sustainability” are two separate problems. California didn’t ban fur because of “sustainability” concerns — the state banned fur because legislators viewed killing animals for fashion as cruel.

This is in line with the population’s evolving attitude toward fur. In 2016, a Mic.com survey found that 66 percent of millennials weren’t comfortable wearing real fur. A 2019 report from Boston Consulting Group revealed that Gen Z rated animal welfare as their top sustainability issue when it came to purchasing luxury goods.

I looked back in the news archive to try to figure out when discussion of fur as a “sustainable” material started. One early mention appeared in a September 2005 Evening Standard article about “Breitschwanz lambswool,” also referred to as broadtail, which had been popular on runways that season and comes from infant or fetal lambs. Despite the fur industry denying this sort of thing was happening, one Humane Society investigator managed to film pregnant ewes being slaughtered and fetal lambs cut from their stomachs.

You know what the response to this was, on the fur side? Andrea Martin from the British Fur Trade Association told the paper (emphasis mine), "They [Karakul sheep] are bred for their milk, meat, fleece and pelt. The farmers are trying to make a living in a harsh and inhospitable environment, using a sustainable-natural resource…”

The fur industry used this talking point again and again and again — and it has probably gone a long way toward delaying the inevitable fate of real fur, which is likely go completely out of fashion in millennials’ lifetimes. In 2006, the Western Standard, a Canadian magazine, reported on the sudden, surprising profusion of real fur in retail stores.

Call it a comeback for an industry once dismissed as a throwback. And at least some of the credit goes to the savvy marketers at the Fur Council of Canada, which is turning the tables on the anti-fur left. How? By marketing all-natural fur as the eco-friendly fabric, unlike environmentally harmful faux fur, which is made from petroleum products.

If the fur industry wanted this PR to confuse consumers — which we see with casual greenwashing that happens all the time in fashion now — it seems to have succeeded. Maxine Bédat, founder of the nonprofit New Standard Institute, which seeks to reform the fashion industry for the good of the planet, said that lumping animal welfare in with sustainability can muddle the purpose of the sustainable fashion movement. “To me, the whole confusion [over fur and sustainability] encapsulates just how mushy this word ‘sustainable’ has become and how liquid and not very meaningful, bordering on meaningless,” she said.

Bédat worked with New York state lawmakers to introduce the The Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act, which could pass this spring and now has the backing of companies including Reformation, Patagonia, and Eileen Fisher. The bill would require any fashion company with more than $100 million in global revenue to map their supply chains, make disclosures about both social and environmental impact, and set and achieve carbon emissions targets. If passed, the Act would have a huge impact on the industry not only because of the required carbon emissions reductions, but also because brands are likely to clean up unethical manufacturing practices rather than reveal them in embarrassing legally mandated disclosures.

The bill doesn’t say anything about fur. “It’s saying reduce your whole carbon emissions in line with the Paris Agreement,” said Bédat. “So companies, if they are exclusively producing faux fur and that has a massive impact on their climate figures, would have to rethink that.” The same, of course, would be true for real fur.

Another reason harping on the sustainability of real versus fake fur is moot is because it’s hard to say definitively which is worse. I have been covering fur in fashion for around 15 years now, and am yet to see a detailed, large-scale, unbiased study on whether real or faux fur is better for the planet. The four sustainable fashion experts I contacted for this article couldn’t think of any they had seen, either. This is probably because both real and faux fur are just not very widely used textiles. If you’re a scientist aiming to understand the environmental impact of the clothing industry, it makes more sense to invest resources in studying, say, cotton.

If you Google “is fake fur really worse than real fur” you’ll find a slew of articles in trendy publications like Refinery 29 with headlines like, “Faux Fur: Good For Ethics, Bad For The Planet?” This particular story basically gives you a homework assignment, offering lengthy analysis of seven (!) different questions to consider when choosing between a real or faux fur. This article is in good company with more like it that treat real vs. faux fur as enormously burdensome to navigate as a consumer, impossibly nuanced, only answerable after hours of reading and deep soul-searching about one’s own environmental values. Are you, like, an anti-microplastics babe or more of an anti-carbon emissions girlie?

Fashion sustainability expert and journalist Alden Wicker (whose fascinating forthcoming book To Dye For: How Toxic Fashion Is Making Us Sick you must pre-order) argues that the most “sustainable” option, if you want a fur coat real or fake, is a vintage real fur.

The existing research, though flawed, explains her conclusion. Wicker has closely looked at the environmental impact of each material and found two main studies, one from the animal rights side that said faux fur is better for the environment, and one from the pro-fur side that said real fur is best. Further digging reveals that different types of fur impact the environment to different degrees — since mink are carnivores, the climate impact of farming mink is worse than polyester. “But if you're talking about rabbit fur, the impact would drop down much lower. And if you're talking about coyote, which is actually overabundant in North America and caught from the wild (free-range fur, if you will), the impact is even lower,” she said over email.

But that’s just the manufacturing process. What happens at the other end of a garment’s life cycle? Fake fur is commonly made from polyester and acrylic, which are not biodegradable, unlike keratin in fur. Fake fur can also be made from recycled plastic, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that this is “sustainable” since plastic can be recycled up to ten times and using it for clothing takes it out of circulation and, in all likelihood, to the landfill more quickly.

Wicker said, “The pro-fur lifecycle analysis assumed that a real fur coat would stay in use six times longer than a faux fur coat. And that I believe. Maybe our daughters will be walking around in and treasuring our pink faux-fur cropped coats 30 years from now, but I doubt it.”

The Humane Society’s P.J. Smith noted that while the California ban excludes vintage fur, he doesn’t see it as an ideal alternative to a new fur item because it’s not immediately obvious, much of the time, that a piece is vintage. “The biggest issue is if someone sees someone wearing vintage fur and they think that looks cool and then they go out and buy a new fur,” he said. I noted that some of the new fur coats are so real-looking that you could argue it creates similar demand. He suggested accessorizing such a coat with a “fur-free” pin, adding, “The environmental impact of faux fur doesn’t make real fur OK.”

At the end of the day, the most sustainable way to consume fashion is to vote for people who support industry regulation. Also, try to buy sparingly, ensuring you get as much use out of each item of clothing as you possibly can. Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, noted in an email, “Every fiber and fashion material made at scale in our linear fashion system has a large environmental impact, and the idea of a green or greener material is pretty misleading.”

The topic of sustainable fashion can be overwhelming and confusing to understand, thanks in large part to so many brands’ greenwashing and so many publications’ blithe regurgitation of said greenwashing. If you want to read more, check out Back Row’s past coverage on sustainable fashion and fur:

The Maddening Experience of Shopping For 'Sustainable' Clothing

"Sustainable" Fashion Is a Luxury. It's Also a Lie.

A Symbol of Elitism, Fur Is Going Extinct

If you want to go even deeper, my favorite books on fashion and sustainability, in no particular order, include:

Fashionopolis: Why What We Wear Matters by Dana Thomas

Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion and The Conscious Closet: The Revolutionary Guide to Looking Good While Doing Good by Elizabeth Cline

Unraveled: The Life and Death of a Garment by Maxine Bédat

Consumed: The Need for Collective Change: Colonialism, Climate Change, and Consumerism by Aja Barber

Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins by Alyssa Hardy

*And this one isn’t fashion-specific, but provides great background on why industries like fashion need to clean up their acts and why legislation is necessary for doing so: The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming by David Wallace-Wells

Look at that, you made it to the end of this post! You must have liked something here. Why not become a paid subscriber and support the continuation of this kind of journalism? Your subscription fee enables me to operate without the influence of advertisers.

Great post and thank you for all the excellent reading suggestions!

Sustainability is a complicated issue. Cotton uses a gazillion litres of water to produce. Is it "sustainable?" Not in drought-stricken areas, that's for sure. When it comes to fur, it seems some animals are more equal than others (to quote Animal Farm), so it's worth thinking about the type of real fur you're looking at. On the other hand, fake fur will live in landfills for millennia. I think people need to consider all sides of a debate and then make an informed choice.