Discover more from Back Row

"Sustainable" Fashion Is a Luxury. It's Also a Lie.

Greenwashing has become one of the industry's most insidious practices.

Over the past two years or so, the word “sustainable” has been used to the point of meaninglessness in fashion. A recent Vogue.com story offered this, for instance, about the latest Balenciaga collection:

…spring 2022 may have been [designer Demna] Gvasalia’s most sustainable collection yet: 95% of the materials were “certified sustainable,” including organic cotton, recycled polyester and nylon, and upcycled leather and embroideries. The opening gown, an explosion of black lace, was a blend of 63% recycled nylon and 37% responsibly-sourced viscose, while the leather bomber in look 44 was made of a vegan alternative derived from cactus leaves.

This all sounds fabulous, right? “Recycled,” “responsibly-sourced,” “vegan alternative” – it’s a climate-conscious fashionista’s buzzwords starter pack to complement the Impossible Burgers in her freezer.

But if you don’t take a fashion brand’s language as gospel, and find yourself wondering what “certified sustainable” actually means and if viscose, typically derived from plants, can indeed be responsibly sourced, you’re asking important questions to which there unfortunately aren’t satisfying answers. A lot of these claims are, sadly, hollow marketing speak. The technical term for it is “greenwashing,” and it’s designed to appeal to a younger generation who cares more than ever about the impact their purchases have on the planet.

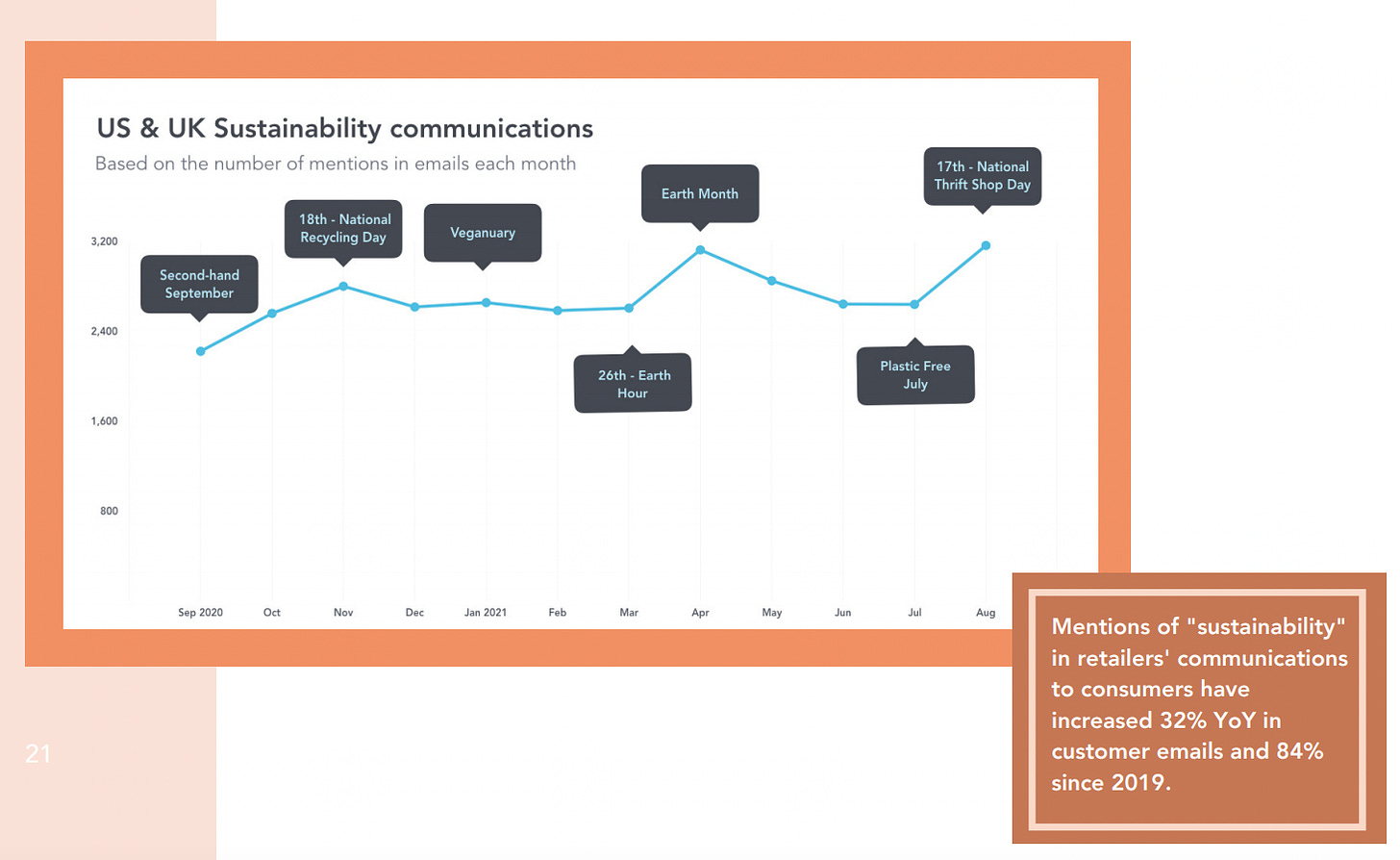

In one 2020 survey by First Insight, 73 percent of Gen Z respondents said they would pay more for “sustainable” items, the majority of those people saying they’d pay as much as 10 percent more. And according to the new annual sustainability report out this week from Edited, which analyzes retail trends, “sustainability” has increased in retailers’ customer emails by 84 percent since 2019.

“The word ‘sustainable’ itself is problematic because the fashion industry is not growing trees. The resources are being used to create things,” said Maxine Bédat, author of the book Unraveled: The Life and Death of a Garment and founder of the New Standards Institute, which advocates for a better, greener fashion industry.

It’s a painfully logical point that’s been pretty brilliantly obfuscated by an industry fixated on telling happy stories about how earth-friendly their fabrics are. “It's so narrative driven, it’s like, I don't know, ‘Look at this beautiful sheep that was massaged,’” said Bédat, noting that these stories help portray sustainability as a luxury good. “I think that's a deep concern because the planet doesn't give a shit about storytelling.”

Her points were echoed by Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion and The Conscious Closet: The Revolutionary Guide to Looking Good While Doing Good and director of advocacy and policy at Remake, which fights for a better fashion industry. “The conversation has been grossly oversimplified to, ‘Fashion is bad.’ ‘This is sustainable. This is not.’ And it is not getting us anywhere,” she said. “The way that brands are using [the word ‘sustainable’] is incredibly misleading and meaningless.”

But “sustainability” comes down to a lot more than materials and fabric waste. It should also account for the human toll of manufacturing, such as the pollution and sea level rise that disproportionately affects communities of color. In his book The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, which focuses on global warming’s impacts on humanity, David Wallace-Wells writes, “[W]arming is not just a matter of sea level, and its horrors will not hit nations like the United States first. In fact, the impacts will be greatest in the world’s least developed, most impoverished, and therefore least resilient nations – almost literally a story of the world’s rich drowning the world’s poor with their waste.” For clothing examples of this, look to Ghana. The BBC recently reported that 15 million pieces of secondhand clothes arrive there each week, much of them fast fashion. The items that are too shoddy to resell go to landfills, where they overflow to beaches then wash out to sea.

Or, look to factories in Guangdong, China. In Unraveled, Bédat describes visiting a denim “wash house” there, where she “crossed many inky puddles – the iridescent, bubbling contents of the industrial washing machines, which turn raw, stiff denim soft and wearable. Nothing was broken. Sloshing chemical runoff was the norm.” She continues:

I ascended the wooden staircase gingerly while the driver looked at me with concern as to whether it was a great idea for me, a pregnant woman, to keep going, noticing that there were gaping holes in the staircase and nothing below. At the top of the staircase, three people stood on the finishing platform (one wore a mask, none wore goggles), spraying a stream of pink liquid, probably the denim fading agent potassium permanganate. The European Chemical Agency classifies it as a “danger,” as it has been found to affect the lungs if inhaled repeatedly, resulting in symptoms similar to bronchitis and pneumonia. Animal testing has also shown that repeated exposure to the substance causes possible toxicity to human reproduction or development.

An untold number of people are making our clothes in these sorts of unsafe working conditions in countries like China and Bangladesh without earning a living wage. Bangladesh was, activists will quickly remind you in any conversation about fashion and sustainability, where the Rana Plaza factory collapsed in 2013, killing more than 1,100 and injuring more than 2,500. Stories from survivors are hard to read. Fashion journalist Dana Thomas visited Bangladesh five years after the collapse and shared survivors’ stories in the New York Times and later in her fascinating book, Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes. From her 2018 Times story:

When he opened eyes in the rubble, he realized he was pinned under a concrete pillar. As everything came into focus, he saw he was face-to-face with one of his good friends, Faisal, who worked on the second floor as a sewing machine operator.

“I’m not sure how,” [Mahmudul Hassan] Hridoy said. “I guess my floor dropped down to his.”

Faisal’s skull was shattered, he said, in a whisper. “And his brains were spilling out.” He began to cry. “I can’t forget how his head exploded in front of me,” Mr. Hridoy said, as he sobbed.

In just one example of how opaque the fashion manufacturing process is, activists had to go through the rubble to look for clothing labels to determine which brands were making clothing in Rana Plaza in the first place (they found Mango and Primark, plus other evidence that Walmart was producing there as well, the Times reported).

Yet when Thomas was doing this reporting in 2018 to see how much things had changed five years later, while many structural repairs to factory buildings had been made, she still witnessed children at sewing machines, exposed wiring, broken window panes, and bolts of cloth strewn on the floor, making a safe exit in a fire impossible.

The problem is that fashion brands contract factories to make their clothes, which subcontract other factories, which subcontract other factories, and so on. Brands are able to wash their hands of what happens more than a step down in the supply chain by saying the subcontracting wasn’t authorized and they weren’t aware of or can’t control what they do.

I asked Bédat how I could tell if a piece of clothing was made in a sweatshop. “Oh, you can’t,” she said without a second of hesitation. The one exception she offered was something labeled fair trade (here’s a list of some clothing brands that are).

Cline said, “I wrote this in Overdressed, but it seems lost on people: I think the whole fashion industry, corporate fashion industry, runs on a fast fashion model. So I don't really make a huge distinction between a Nike, and a Gap, and an H&M, even a Gucci, because they all just operate kind of similarly.” Every so often a story about production happening steps down in the luxury fashion supply chain makes the news, like the report in the New York Times last year about an embroidery factory in India servicing Dior and Saint Laurent, where sewers worked “without health benefits in a multiroom factory with caged windows and no emergency exit, where they earned a few dollars a day” and at night, “some slept on the floor.”

When you consider the industry’s dramatically heightened public concern for “diversity and inclusion” since last summer, the lack of emphasis on human labor in the “sustainability” “conversation” is wild. Then again, the shoe fits: just last week we learned Coach was hawking its purse recycling program while destroying a shocking 1 percent or $42.5 million worth of its merchandise. And the marquee sponsor of the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s big “sustainability” initiative has been none other than Lexus.

Many activists are wary of placing the onus on consumers to shop sustainably. Sure, we can look for products made with organic cotton, but it’s impossible for us to buy ethically made goods if brands don’t have to tell us how they’re making stuff (or how much unsold stuff they’re destroying). Since brands have proved time and again – with devastating consequences – that they won’t do that on their own, governments need to compel them to do it through legislation. Brands are more likely to clean up their acts than own up to embarrassing and shoddy practices. Sustainability consultant and founder of the ethical children’s clothing line Sat Nam babe Jen Coulombe said that after Business of Fashion’s report on the Sustainability Gap came out earlier this year, a brand came to her company for help given how poor their rating was.

Things could change in the U.S. after the Federal Trade Commission reviews and updates its “Green Guide” in 2022. The guide regulates what claims businesses can make about how environmentally friendly their products are. So, it’s possible brands won’t be able to call their stuff “sustainable” once those rules go into effect.

Not buying clothing is, for many of us, not realistic. But Bédat encourages people to be thoughtful about it. “The biggest driver of impact reduction is not any process that a brand does, it is how often that garment is worn. So even if you get a polyester thing that's made by H&M, but it's quality enough and you like it enough that you are wearing it a lot, that's going to be a more sustainable thing than a highly marketed ‘sustainable’ thing that you don't like and don't wear.”

This post is free, so feel free to forward it. Support independent fashion journalism like this, free from advertiser pressure, by subscribing to this newsletter.