Discover more from Back Row

The Maddening Experience of Shopping For 'Sustainable' Clothing

Reading the fine print feels like calling Verizon.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. If you like these emails, please tap the heart at the top of this post and forward them to your friends. The best way to support Back Row, which is ad-free and free to read, is to buy a copy of my book ANNA: The Biography, a New York Times bestseller and great beach read. If you are new here, subscribe to get emails like this sent to your inbox around twice a week.

Earlier this month I got an eyebrow raise of a PR email with the subject line “Zara releases limited-edition line of sustainable fashion, made from carbon emissions.” Zara is a brand that, according to WSJ.’s August 2021 profile of Marta Ortega Perez, daughter of Zara founder and one of the world’s richest people Amancio Ortega:

…sells more than 450 million items per year of womenswear alone, and new items arrive twice a week at Zara stores and online, including a dizzying carousel of bags, shoes, lingerie, menswear and children’s clothing, home goods, perfume and Zara’s recently launched bridal wear and cosmetics lines.

You would think a company that sells more than 450 million items of womenswear “alone” would not qualify as sustainable, unless you consider “sustainable” to mean that the way they’re making clothes now is better than what they could be doing. The email touted a company called LanzaTech:

LanzaTech's technology captures CO2 from industrial, agricultural, or domestic waste processes. Through a fermentation process, it is transformed into ethanol, a fundamental component in producing materials like PET used in a polyester thread. The final PET contains 20% MEG (Monoethylene Glycol) made from recycled carbon emissions and 80% PTA (Purified Terephthalic Acid).

If you are confused or find your eyes glazing over, welcome to the world of “sustainable” clothing shopping in 2022 — a simultaneously hopeless and hopeful place, where reading the fine print feels like calling Verizon.

Explanations about precisely how specific items of clothing are “sustainable” are maddening and verbose, pastiches of textbook-style jargon, trademarked pronouns, and vague but good-sounding claims, accented with cute recycling symbols. Nearly all of it begs for independent fact-checking. Yet when concerned citizens, who just want a new top that isn’t made in a factory that pollutes rivers, embark on their own research to verify or simply understand what they’re being told by clothing companies, they’re likely to find that the claims often range from questionable to outright bullshit.

In the largely unregulated wild of clothing companies bloviating about their conscientiousness for our planet, their claims tend to go in one of two directions: either weighed down by science speak, or reliant on buzz terms like “plant-based.”

Zara provides an example of the former. That PR email linked to some items in Zara’s “Join Life” collection. The fine print on items in this collection tell us that this is Zara marketing speak for “items that have been produced using technologies and raw materials that help us reduce the environmental impact of our products.” Under “contents and care,” you’ll find 288 words explaining exactly how and why Zara says that this $45.90 going-out top reduces its “environmental impact.” The going-out top copy, in fact, contains a section specifically devoted to its “outer shell”:

This fiber is obtained from wood from sustainably managed forests where trees are grown in a controlled manner. What's more, the manufacturer of this fiber is certified as "green shirt" in the Hot Button Report developed by the non-profit organization Canopy, thus guaranteeing the protection of old-growth and endangered forests.

Additionally, technologies are used in its production process that comply with parameters established by the European Union of more responsible consumption and management of energy, water, and the reduction of CO2 emissions.

Because we all must watch scraps of video all the time now, Zara enmeshed in this fine print a little clip of woodchips being lovingly fondled on a conveyor belt and water filling a measuring vessel. It’s like the ASMR of clothing factory videos, attempting to hypnotize consumers into believing that the mere act of purchasing this item borders on a charitable deed when it’s actually more like giving our planet a condescending head pat.

Now, let’s say you are in the market for going-out tops (YOLO?), and would ideally like to buy something “sustainable.” Let’s turn to favorite going-out shopping site Revolve, which has a “sustainability shop.” Each item in this section comes with one or a smattering of symbols, above which one can hover to learn why exactly each product is “sustainable.”

This $99 floral bustier top comes with two symbols, one for “plant based”:

Plant-based materials are made with fibers derived from sources such as bark, wood, or cotton, and not from animals.

And one for “responsible manufacturing”:

Responsible manufacturing focuses on improving the workplace conditions under which a brand's products are made or the environmental impact that may result from the manufacturing proceses [sic]. This category may include products that are locally made within the brand's own community or country, as well as artisan made, supporting traditional or age-old techniques.

This sounds good but is so vague as to be meaningless unless a shopper is willing to seek out more detailed information on a specific brand.

But more research is likely to lead to more confusion if not outright exasperation. Over the weekend, the New York Times published a story about how synthetic materials like “vegan leather,” formerly “pleather,” became a gold standard for environmentally conscious dressing. The Times blamed something most people have probably never heard of called the Higg Index, which purports to tell clothing companies which materials are best for the planet. The index steers companies away from naturally occurring materials like leather and silk in favor of synthetics made from fossil fuels. It relies on research that some experts say is questionable since it was funded by producers of synthetic materials — like pleather — and was not subject to external review.

The Times notes that the proliferation of “vegan leather,” for instance, has had upsetting consequences. In 2020, a reduced demand for leather meant that “a record 5 million hides, or about 15 percent of all available, went to landfills, according to the U.S. Hide, Skin and Leather Association, a Washington-based trade group.”

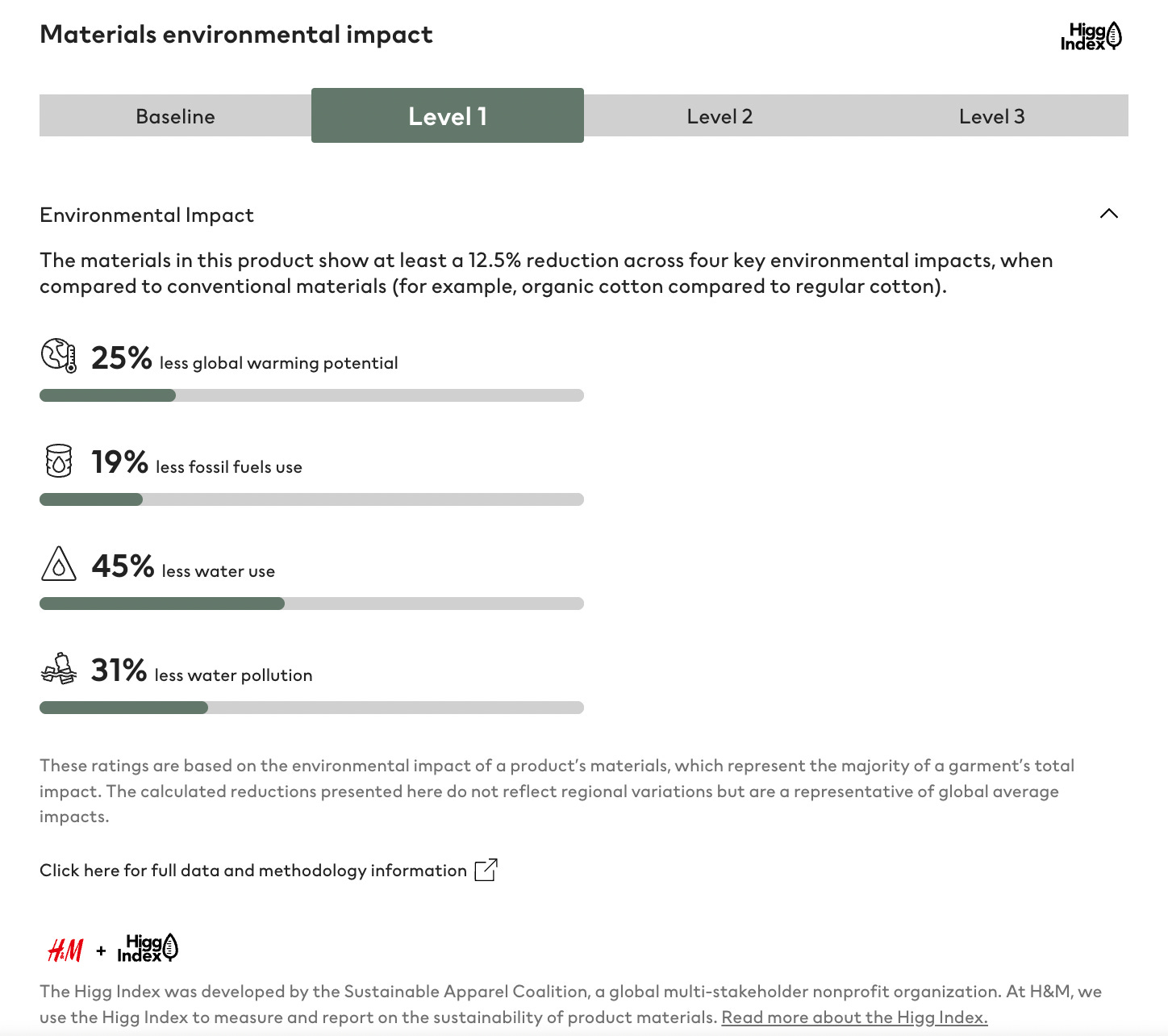

The Sustainable Apparel Coalition that runs the index boasts members like Amazon, Asos, Boohoo, and H&M — fast fashion companies that rely on synthetic materials. H&M even has something called a “Higg index sustainability profile” displayed on some of its items. Per H&M:

Each product is given a score based on the environmental impact of the materials used to make it. Scores range from “baseline” to “3.” Baseline scores are given to products made from conventional materials and scores of 1,2 and 3 are given to products made with materials that have lower environmental impacts. On each product, customers will also see detailed data on impacts relating to water use, global warming, fossil fuel use and water pollution.

Going back to our search for going-out tops, here’s a $19.99 one that has a “1” rating, which appears like this on the H&M site:

You can even click out for more information in a new tab — nearly 600 words more of information! But what does it matter if you then decide to research Higg further, land on the Times article, and decide you agree with the experts suggesting that the whole thing is meaningless? (The Times also spoke to people who defended the Index.)

The biggest fashion media outlets aren’t usually much help either, when it comes to figuring out what is and isn’t environmentally OK. Many consumer-facing media websites profit off of purchases through affiliate marketing programs, and are therefore incentivized to market clothing the same way apparel companies do. For instance, Vogue.com has a roundup of “eco-friendly swimsuits for mindful summer swimmers.” The majority of the selections boast of “recycled” materials, though it’s difficult to discern from the Vogue.com copy alone what exactly this means. One featured brand is Peony, which Vogue.com says offers swimwear “100% made from recycled fabrics.” Over at Peony’s site, we can learn more about their exclusive trademarked fabric called “Repreve®” (emphasis mine):

Our textured swimwear fabrics are developed in-house exclusively using REPREVE® regenerated fibres. These fabrics are unique to peony, as we design from the yarn, determining the weave, weight, stitch, colour and design. Made from 100% recycled plastic bottles, our use of REPREVE® gives new life to plastic waste that would otherwise end up in landfills or the ocean, emits reduced greenhouse gases and conserves energy and water in the process.

It sounds good, turning recycled plastic into Vogue-approved bikinis. However, it’s not hard to Google recycled textiles and find this Guardian article about how fabrics made from recycled material — while in high demand by apparel companies trying to reduce their environmental impact — aren’t necessarily better for the planet:

[Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, the most common type of plastic] bottles are also part of a well-established, closed-loop recycling system, where they can be efficiently recycled at least 10 times. The apparel industry is “taking from this closed-loop, and moving it into this linear system” because most of those clothes won’t be recycled, said [Maxine Bédat, executive director of the New Standard Institute, a non-profit pushing for a sustainable fashion industry]. Converting plastic from bottles into clothes may actually accelerate its path to the landfill, especially for low-quality, fast-fashion garments which are often discarded after only a few uses.

There is hope, however, for a future where shopping for sustainable clothing is regulated and much less confusing: the Fashion Act is a bill in New York that would require fashion companies with global revenues exceeding $100 million to make certain disclosures to consumers, such as mapping at least 50 percent of their supply chains, stating at what points in the supply chain they have the biggest environmental and social impact regarding things like worker wages and water use, and create plans to reduce carbon emissions. Though this is a state law, it’s significant in that it would apply to global brands ranging from Zara to Louis Vuitton, and the disclosures would need to be available online, meaning anyone could see them. Rather than be forced to make embarrassing disclosures, these companies are likely to really try to clean up their acts first. The act would also relieve consumers of the burden of doing their own research on an item’s environmental impact.

But in the meantime — and if the act never passes — consumers will be left to figure out if they believe all the brands claiming their clothes are “sustainable.” And brands have little to no incentive to tell people that the most sustainable way to shop is to simply buy fewer things you love that are made well enough for you to wear them a lot before you discard them. Instead, brands are incentivized to confuse well-intentioned people. This works because fashion has long relied on consumers taking its word as gospel. This is how the industry regularly manages to convince us of outlandish things, like that some shoes should cost $800, or that all your skinny jeans have become embarrassing, or that you need designer shell jewelry for your summer vacation. Fashion is confusing and opaque by design. It’s no wonder the “sustainable” category is too.

Don’t forget to subscribe and support independent, ad-free fashion journalism.

This is where third-party certifications can be really helpful. Though they are not 100% perfect (nothing is), they can make the shopping experience easier.

Buying second-hand or going through swap communities can also be an option that requires less research, though that can be dependent on where you live and what you are looking for.

I have learnt, overtime, to try to wear my clothes until literally they can't be worn anymore. Over 15 years ago I worked in Patagonia and still wear a lightweight fleece which is impeccable, and several other garments from that era. With my children I use a combination of hand me downs, previously owned and some new. And I've started buying vintage coats and jackets, especially, and visiting my mom's closet for good quality clothes she's had for over 40 years and doesnt' wear anymore.