Linda: The (Mini) Biography

How Linda Evangelista came from nothing, became an icon, and had her life ruined by the pursuit of beauty.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. In this issue, I’m trying out a new feature: a mini biography. Think pocket-sized bios of fashion icons, a life story told in the style of a book, only much shorter because this is not a book. (If you want a whole book by me, you know what to do.) I’m starting with Linda Evangelista. Many of us are thinking about her following the release of her September British Vogue cover story, photographed by Steven Meisel. If you have requests for future (mini) bios, please DM me on Instagram or reply to this email.

If you are a free subscriber, this one’s on me. Upgrade to a paid subscription to receive two Back Row posts per week, exclusive fashion week coverage starting next month, and access to the complete Back Row archive and commenting.

What paid Back Row subscribers are reading:

Linda: The (Mini) Biography

She had “the look.”

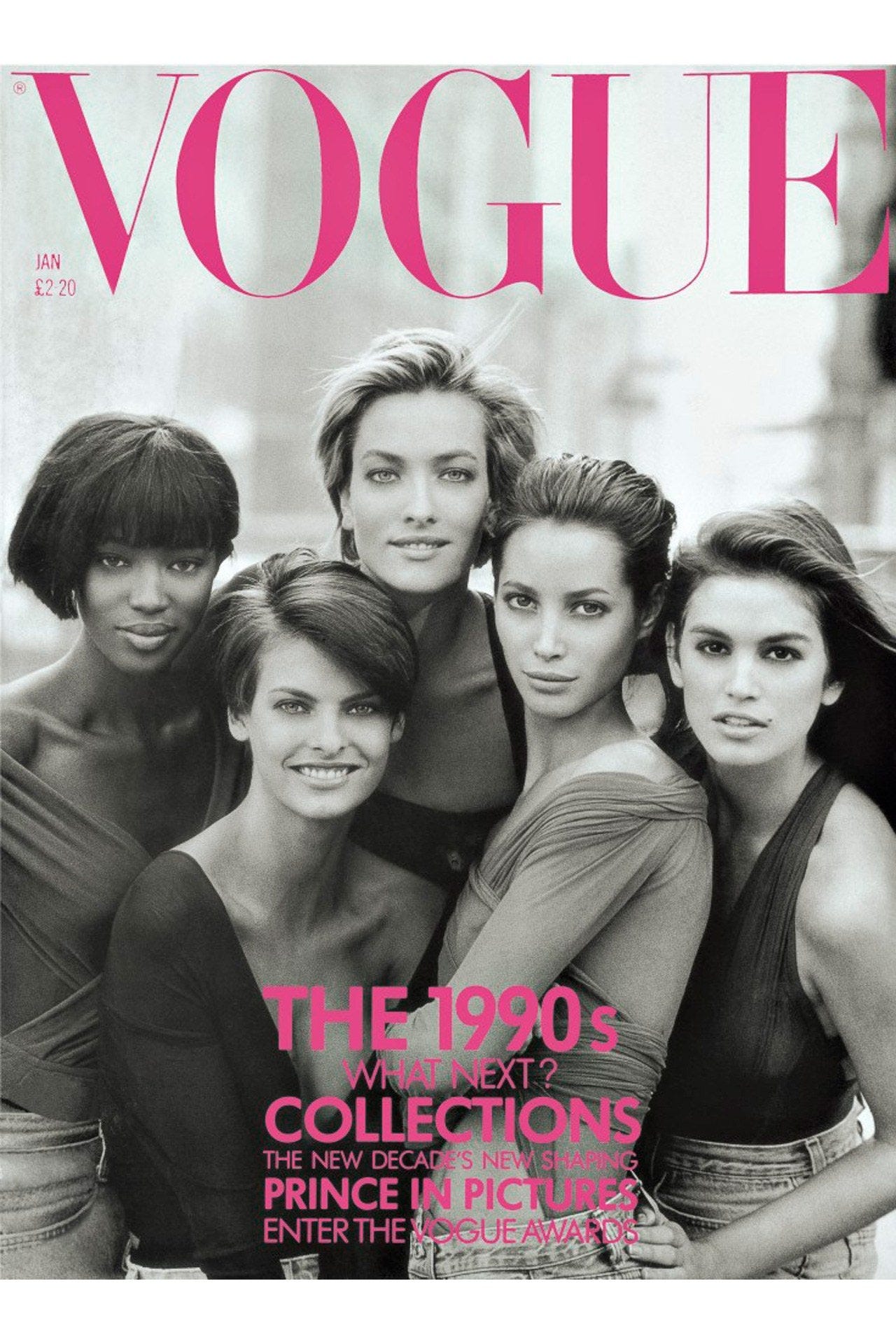

One modeling agent told the New York Times in 1989 that this was something that could not be explained, but only felt. Linda Evangelista was, thanks to that inexplicable look, among roughly 300,000 working models in New York. She happened to be among the handful — including Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, and Christy Turlington — able to ultimately command staggering rates of $10,000 a day. Or more.

Fashion had been so homogenous that Linda was seen as somewhat exotic-looking when she came up in the late eighties. She told Vogue in 1990, when she was nearing the peak of her career, “For so long it was always blond-haired, blue-eyed button noses. That kind of model is only capable of one look. Christy and I are are versatile. We can do teenybopper, and we can do sophisticated and forty-five. You can put fashion on us. You can’t put Christie Brinkley in Chanel. When I’m on a job with lots of girls they always save the ugly dresses for me. ‘Oh, Linda can do this. She’ll make it look good.’”

In their heyday, the supers weren’t just the faces of fashion, they were something like the reality stars that would postdate them as cultural obsessions. Neither Instagram followers nor famous parents were necessary for them to gain entrée to the fashion industry. They were miraculously discovered, then launched into glamorous, jet-setting lives. They were everywhere, documented feverishly by the press, which loved to both praise them and hold them in contempt.

Linda seemed to enjoy soaking up the spotlight, but she also played a certain part the reading public likely craved. She’d show up an hour late for an interview. On jobs, she’d make demands that the press cast as petty. Maybe some of it was intentional, maybe she just figured, fuck it! And decided to just be herself since her career was supposed to be short anyway.

“You have to realize, a model's professional life is not very long-lasting. After two years, designers and photographers tend to get tired of you,” said Ellen Harth, president of the runway division at Elite, which then represented Cindy and Naomi, in the New York Times in 1990.

Linda, Naomi, and Christy were called “the Trinity.” During the fall of 1990, they were seen “zooming everywhere together in a Rolls Royce,” Women’s Wear Daily reported. Linda and Christy were best friends. “They have to be next to each other in the dressing room,” one industry person told WWD. Their fees had been an object of media fascination by that point. The papers loved reporting on what the supers were earning, and certain fashion executives loved boasting about how they weren’t foolish enough to pay them. Modeling was one of the only industries where women earned more than men, yet the idea that these women could earn this much was generally written about with a heaping side of disbelief.

In September 1991, Women’s Wear Daily reported that Linda’s average fee for a single fashion show was $6,000, though Lanvin had the previous season paid her $20,000. The story was about how the cost of putting on runway shows was “out of control.” Of course, models are just one of the many costs associated with staging a fashion show, but this received a disproportionate amount of scrutiny. WWD printed, “What seems to irk fashion executives most are the extravagant fees that top models demand. By some estimates, these fees have quadrupled in four years.” (In 1995, the paper reported Linda’s fee to be $10,000.) The fees ballooned in part because designers were hiring editorial models for runway jobs, which hadn’t been the standard.

But in October 1990, an unnamed designer — “one of Paris’s best” — told WWD, “I will not pay $8,000 for a mannequin.” But the supers were, of course, more than that. The designers who did pay them, like Gianni Versace, were able to translate supermodel iconography to their brands and profits, cementing the place of certain collections, ad campaigns, and runway shows in fashion and pop culture history.

Linda told British Vogue, “Gianni really believed in me, not just as a model – he wanted me to shine as myself.”

Of all the Supers, Linda may have been the most quotable.

She was unapologetic and honest in a way that public figures, especially models, who are taught to keep quiet and do their jobs, seldom seem to be these days. In 1989, she told Canadian magazine Chatelaine, “I take more than a hundred flights a year… I could draw you a plan of any airport in the world.” On a night out dancing in 1990, Newsweek reported her saying, “We don’t vogue. We are Vogue.” When she was profiled in Vogue along with Christy in 1990, she delivered what became one of the most famous fashion person quotes ever when she said, “We have this expression, Christy and I... We don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.”

Born to Italian immigrant parents in St. Catharines, Canada, Linda knew she wanted to model from age 12 but her parents were reluctant. Her father worked for General Motors and her mother was a bookkeeper, and they couldn’t afford to send Linda to modeling school, though they were able to enroll her in etiquette classes. “I was tall, and people used to tell my mum, ‘Oh, she’s tall. She should be a model.’ That, and I was obsessed with fashion,” she told British Vogue.

She entered the Miss Teen Niagara pageant at 16 and lost, but caught the attention of an Elite talent scout – only her parents wouldn’t let her pursue modeling until she finished school. She got a contract to model in Japan the summer she was 16 — but the trip was a disaster. When she got to the airport, no one was there to get her. She made it to her apartment, which she found to be “dirty,” and occupied by a roommate who had a boyfriend living there. “I went to the agency and it was all, ‘Take your clothes off, we need measurements,’ but they already had my measurements. They wanted me naked and it wasn’t a ‘Would you do nudes?’ conversation, it was a ‘You will do nudes.’ I left and called my mother and she said, ‘Get out now and get to the embassy.’ So that’s what I did, and they got me home,” she told British Vogue. In 1984, after she graduated, she moved to New York. That same year, she landed the cover of L’Officiel. By the following year, she had started doing jobs for Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel and had a place in Paris.

She continued booking top jobs: a commercial for Yves St. Laurent’s Opium fragrance, magazine covers, Vogue editorials — countless editorials, really.

Her wavy brown hair fell somewhere around her shoulders in many of these images. Linda was unafraid to articulate her preference when it came to her bookings. “I don’t like doing magazine covers,” she told Chatelaine. “If you work for Vogue, you make about $200 a day. It’s really pathetic. TV commercials are more fun and exciting and they pay well: I’ve made up to $12,000 a day.”

In 1988, she was cast for one such Vogue editorial styled by Grace Coddington. Peter Lindbergh photographed her in Santorini modeling colorful pieces from the resort collections alongside Carré Otis. But it was Linda who landed the editorial’s opening two-page shot. Laughing over an ironing board situated on a vista overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, a stray cat appearing to have wandered into the frame, she wore fuchsia silk charmeuse shorts by Ralph Lauren, sneakers, and no top — all the better to draw attention to something credited in tiny type on the righthand side of the page: her haircut, by Julien D’Ys.

The day the haircut took place in Paris, D’Ys was “very nervous,” he later said. He gathered her hair into a ponytail, cut it off, and then cut more, until what remained was a completely short style with some length on top, allowing short waves to flop onto her forehead just above her eyebrows. Recalling the day in 2015, he said, “I didn’t know what I was going to do until I started doing it… My inspiration was in my head. In America, I had seen a box of Florida oranges that had a picture of a little boy with a bob haircut on it. It reminded me a bit of the Beatles.”

Recalling that day in a 1990 profile, Linda said, “It was Peter Lindbergh's idea… And I was terrified. I asked everybody if I should do it and everybody said no. Everybody including my mother. She said, 'Don't cut your hair. Everybody has long hair.' And I said, 'You're right. Everybody has long hair. I'm going to do it.' But I was scared. I cried through the whole thing. I lost my confidence for weeks. I thought I looked ugly. The first show I did in Milano I came out and everybody gasped. And I thought they hated it."

D’Ys had a different view. “She carried it perfectly,” he said.

The culture agreed. “Short hair used to be the kiss of death for fashion models, who needed the versatility of long tresses. But now the above-the-ears crop is suddenly the international rage. Credit Canadian model Linda Evangelista, whose daring haircut… looks so new that she’s become one of the Elite modeling agency’s hot properties, right up there with long-haired mannequins Paulina Porizkova and Cindy Crawford,” is how a May 1989 Los Angeles Times story put it. After that Vogue story came out in the December 1988 issue — Anna Wintour’s second as editor-in-chief — the article continued, “other models headed for their hairdressers. By last month, Evangelista clones had turned up on the runways of every major-designer fashion show in New York.”

The cut was referred to as “the Linda Evangelista” or “the Linda.” It became so famous so quickly that Oscar de la Renta VP Jack Alexander said in a November 1989 New York Times story that after she cut her hair short, “The designers all said that only short hair looks modern.” Linda later said that the haircut quadrupled her rate. She became the face of Perry Ellis, selected by then-designer Marc Jacobs for the fall 1989 ad campaign. He called her hair “just the right thing at the right time.”

But for Linda, the frenzy over her look quickly became rather strange. “Now, all the magazines are writing about how I cut my hair, and girls all over the world are doing it. At first, I was flattered when I saw all these girls cutting their hair off. But they’re cutting it exactly the same, and it’s my haircut. It’s a bit much,” she told Chatelaine.

At this point, now 25 years old, she felt like her ambitions had been realized. Asked about her regrets, she said, “In the beginning… I didn’t stand up for myself. I let makeup artists and photographers push me around… Now, if I arrive on a shoot and there’s the slightest bit of ‘attitude,’ I’ll walk. Nobody pushes me around.”

George Michael was burnt out on fame in 1990 when his second solo album Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 came out.

He was prepared to take the unprecedented move of not touring or making any music videos to promote it. He said, “[M]ost people find it hard to believe that stardom can make you miserable. After all, everybody wants to be a star. I certainly did, and I worked hard to get it. But I was miserable, and I don’t want to feel that way again.”

Michael later did agree to film a video for “Freedom! 90,” but declined to be in it. Instead, he decided to cast the group of models he had seen on the January 1990 cover of British Vogue shot by Peter Lindbergh, including Linda, Christy, Cindy, and Naomi, along with Tatjana Patitz. The video was directed by then-up-and-comer David Fincher.

But even for Michael, one of the biggest pop stars of the time, and even for a music video, which offered models a taste of acting crossover work they were thought to crave, it wasn’t easy. They needed convincing. “They were relentless about getting these girls,” said Elite booker Ann Veltrie.

Linda shocked everyone by showing up with her bob — her iconic bob — in a new platinum shade. She had dyed it the night before when she was on another job with photographer Steven Meisel. The crew at first thought was a wig.

The “Freedom! ‘90” video premiered on October 30, 1990, and went into heavy rotation on MTV, aligning the supers with music and entertainment more broadly. The tone around Linda’s hair color now was much different from when she got it cut in 1988. “Will the new color cause American women to head for the Clairol counters? Probably not, most fashion watchers here think. She was stronger and classier looking with her own dark hair,” printed the Chicago Tribune in November of 1990. “The color, unfortunately, washes out her striking features and will likely not be followed by her colleagues,” wrote the Toronto Star around the same time.

Not inspiring copies may have been, for Linda, entirely the point. But that’s not to say she didn’t mind the criticism. According to a report at the time, she was at a party when she mistook a Bloomingdale’s executive for a journalist whom had written something disparaging about her hair, and yelled, “Lay off me!”

In a December 1990 Toronto Star profile, Linda was open about how she felt about what Women’s Wear Daily had printed about her hair. “They’re evil,” she said. "I told them, 'I didn't know you people were hair critics. I thought you were fashion critics.' But it didn't make any difference. I didn't lose any clients or bookings."

By the end of 1990, she had appeared on 60 magazine covers.

By the time Gianni Versace showed his fall 1991 collection, the world’s most in-demand models were earning $50,000 for half an hour of work.

Unlike the executives who were complaining about it in the media in the late eighties, Versace had outbid other designers to get the top girls to walk in his show. He had had an epiphany about casting it, thanks to the editor-in-chief of British Vogue at the time, Liz Tilberis, responsible for publishing the cover that inspired the “Freedom! ‘90” video. She told him to use the same women in his fashion show that he used in his ad campaigns.

The models walked down the runway in thigh-high black platinum boots and bright-colored pleated mini-skirts. Naomi wore her hair in a bob, Cindy’s cascaded around her shoulders like bouncy cotton candy, and Linda’s was still in that striking platinum blonde. They walked down the runways solo and in different pairings, which was atypical for a runway show, but had the effect of reinforcing their star power. Fashion journalist Tim Blanks would later reflect, “As the show went on, you could feel that there was something kind of orgasmic coming.”

As the show ended, “Freedom! ‘90” came on and Linda, Cindy, Naomi, and Christy bounced down the runway in mini dresses, arms around each other, singing the song. Many years later, Cindy would describe it in Vanity Fair as her most iconic moment as a supermodel, saying, “It felt like all the stars had aligned.”

Yet around this time, the press may also have begun to feel something of supermodel fatigue. Or maybe it was that age-old habit of building women up seemingly so that one day in the future, they can be taken down. In March 1991, Women’s Wear Daily wrote, “The one thing everybody in Paris is sick of is Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington. Sending these two models down the runway together has become a fashion cliché.” Though Linda had said in 1990 that neither of them would get up for less than $10,000 a day, Turlington was making $12,500 a day for commercial jobs. Linda joked in a 1991 San Francisco Chronicle article, “We used to work as a package deal. Get two for the price of — four!”

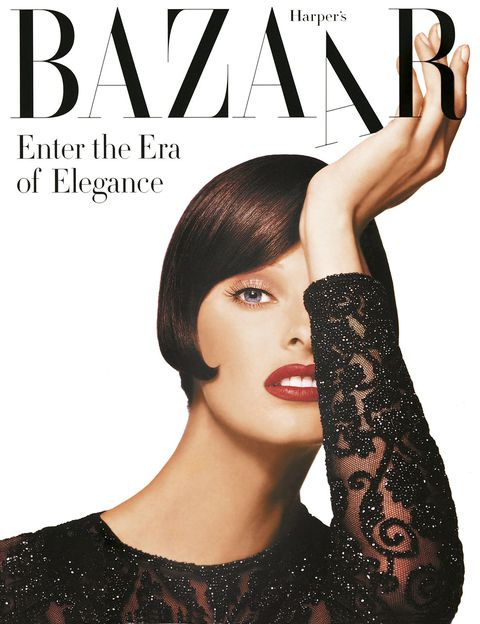

If everyone was sick of them, it hardly showed. When Liz Tilberis took over Harper’s Bazaar in 1992, it was a big deal because she presented the biggest threat up until that point faced by Anna Wintour at Vogue. Tilberis set about staffing her magazine with all the top people. She poached staff from Vogue and awarded contracts to fashion’s top photographers, whose rates had long been more outrageous than the supers’. (She was rumored to have spent upwards of $1 million each on Patrick Demarchelier, who photographed her first cover, and Peter Lindbergh.) Her choice for her very first cover for September was, unsurprisingly, Linda, photographed by Patrick Demarchelier. When it came out, the competing fashion editors on Anna’s team at Vogue took note. They knew, one told me in an interview for ANNA: The Biography, that this was really good.

In 1993, at 28 years old, Linda divorced her husband of five years, Gerald Marie, who ran Elite in Paris.

They had met in a nightclub after Linda moved to Paris at 19 to pursue modeling. He owned an agency called Paris Planning, and Linda, unhappy with her representation, left to join his, which eventually combined with Elite.

Their initial meeting, Linda said, was “not at all” love at first sight. "Then one day we were at a dinner party and we looked at each other and we split," he told The Toronto Star in 1990. They quickly moved in together. "Then he started speaking about marriage," Linda said. "I never ever thought he would get married. So I said, 'Well, put the ring on my finger and then we'll talk about it.’ And he did. When I was on my way back here for Christmas we had a dinner right before I left and he put the ring on my finger and I went into shock." On July 4, 1987, when Linda was 22 years old, they got married.

During their marriage, Linda occasionally remarked upon how she rarely even saw her husband. If she spent one week out of the month with him, that was considered “good,” he said.

Linda loved her career anyhow. "I like everything about my job," she said. "I like the traveling. I like the money. I like seeing myself in the magazines. I love clothes. I've accomplished what I wanted. I mean, how many people like their job? Okay, so it's hard to hold a position for 30 minutes. But I think about bank tellers who stand on their feet all day. I always think where I would be if I wasn't here."

Linda never thought her modeling career would last as long as it did.

“When I started in the business, I was told I had three good years in me,” she said when she was 32, her career still going strong. “Every year, I heard that clock ticking and was conscious that it could be my last. I'm not dumb.” Yet, she never made public attempts at crossing over into anything because there was never anything else she wanted to do. But by her early thirties, the end of her career was just about all reporters who got time with her could ask about.

In 1997, she signed a lucrative contract to be the face of Yardley cosmetics, which was described by the British Independent as having “a rather old-ladyish profile.” (Also described as embarrassing for her in this story was the 1996 commercial she appeared in for Pizza Hut, alongside Cindy.) But Linda revealed that she had an unspecified end date in mind for herself. She said, “After my modeling career, having children is my biggest other goal in life. I haven't done it yet because I know I will never work again once I do. I still want to work, I love to work, and I will not schlep my kids around on planes or hire nannies. When it happens, and it will, I want to be a hands-on mother. I can't commit to that right now.” She went onto say, "Beauty has nothing to do with youth. The aging process is a beautiful thing and I don't think magazines agree with that.”

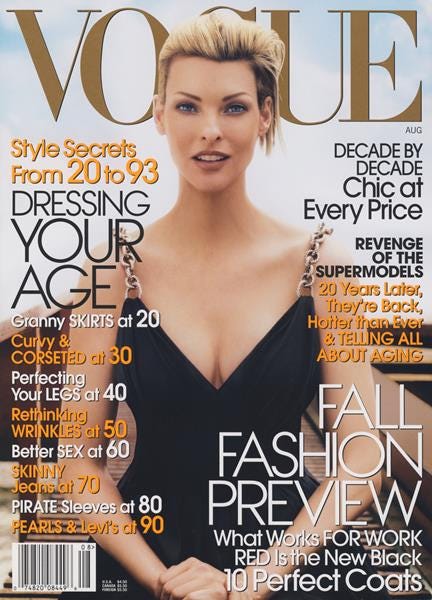

By 1998, celebrities were taking over magazine covers, and the era of the supermodel was ending. Linda was in the papers for “erratic behavior” displayed at a fashion show in Portugal. Georges Marmelo, who covered the event for a local newspaper, told The Ottowa Citizen, “The first time she came to the stage she almost fell down the stairs,” and, “We noticed right away she was abnormally fat for a model.” After this story, Linda announced her retirement and moved to the French Riviera. She fell away from the public eye for three years – until she appeared on the cover of the September 2001 issue of Vogue. She told the magazine, “When I went into retirement I started eating pizza and pasta and bread. Besides walks along the Mediterranean with the dog, I didn't do much at all. I enjoyed not doing my hair or makeup and I wore flat shoes the whole time. It was the best vacation.” Only, it wasn’t enough for her. “I got sick of seeing really ugly pictures of myself in the tabloids. I'd look in the mirror and say, Where'd she go?” Perhaps at least part of her agreed with those magazines that didn’t see aging as beautiful. She had once convinced the world that short hair was fashionable, but the universal act of aging was a different story entirely.

At 41 years old, Linda was back on the cover of Vogue for the August 2006 issue. This time, she was pregnant – only the father of her son remained a mystery. In a public court battle over child support when her son Augustin (“Augie”) was six years old in 2012, his identity was revealed. Apparently in 2005 in St. Tropez, Linda had had a whirlwind romance with billionaire Francois-Henri Pinault, the chief of Gucci parent company Kering, and one of the wealthiest and most successful fashion executives of all time. When she told him she was pregnant, he admitted in court, he broke up with her.

Her years in the limelight seemed to be over. But her romantic relationships wouldn’t stay out of the headlines. In 2020, her ex-husband Gerald Marie was accused of rape and sexual assault by former models. One was Carré Otis, with whom Linda appeared on the cover of that famous December 1988 Vogue. Otis alleged that when she was 17 and living in the spare room of Marie’s apartment — a period when he was dating Linda — he raped her repeatedly. (She said Linda was not there when this happened, and gave no indication that she believed Linda knew about the alleged incidents.)

Linda told the Guardian in 2020, “During my relationship with Gérald Marie, I knew nothing of these sexual allegations against him, so I was unable to help these women.” She added, “Hearing them now, and based on my own experiences, I believe that they are telling the truth. It breaks my heart because these are wounds that may never heal, and I admire their courage and strength for speaking up today.” By this year, the number of victims making sexual assault allegations against Marie had swelled to 15. Through a lawyer, Marie has been saying the allegations are false.

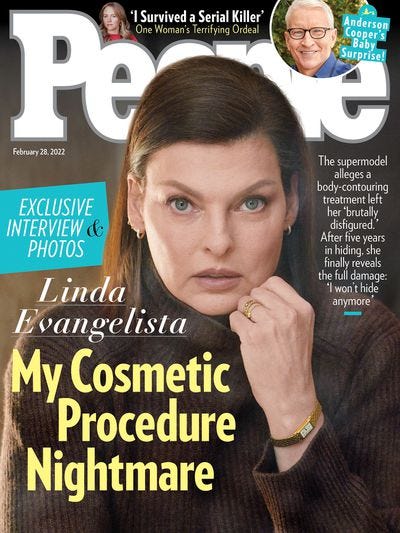

At age 56, a different kind of magazine story would come to define Linda.

She had been in magazines for her cool, era-defining haircut, for her individualistic beauty, for her love of modeling and fashion and dedication to both. Her longevity was a result of her status as an icon synonymous with a beloved time in fashion. But her iconicity was surely also a result of her being so frank with the press for so long. Now, she sought to explain why she had been hiding something. “My Cosmetic Procedure Nightmare,” read the headline on the cover of People’s February 2022 issue, Linda looking more her age than she ever had on a magazine cover.

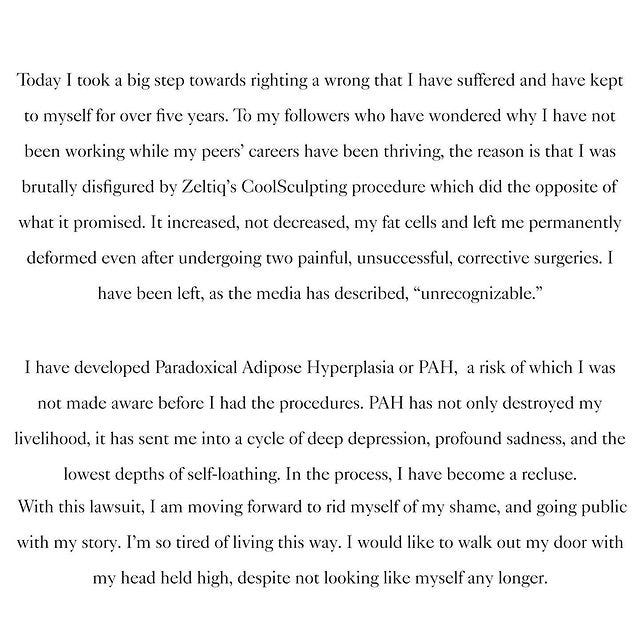

In September of 2021, she had posted to Instagram about how a CoolSculpting procedure had “brutally disfigured” her. “To my followers who have wondered why I have not been working while my peers’ careers have been thriving, the reason is that I was brutally disfigured by Zeltiq’s CoolSculpting procedure which did the opposite of what it promised. It increased, not decreased, my fat cells and left me permanently deformed even after undergoing two painful, unsuccessful, corrective surgeries. I have been left, as the media has described, ‘unrecognizable.’”

The People cover story brought a public end to what she described as nearly five years of living in seclusion. “I loved being up on the catwalk. Now I dread running into someone I know,” she said. “I just couldn't live in this pain any longer. I'm willing to finally speak.”

She explained that after she got the CoolSculpting treatment, the parts of her body she had wanted to be smaller, around her chin, thighs, and bra area, actually got bigger. She was diagnosed with paradoxical adipose hyperplasia, a rare side effect that causes fat cells to harden and multiply.

A lifelong devotion to physical beauty had led to fame and fortune. Yet now, in a cruel twist, it had left her maimed.

This month, Linda’s British Vogue cover came out shortly after a new Fendi campaign, marking a return to capital F Fashion that Linda had missed. She spoke to Sarah Harris about the CoolSculpting nightmare again, including the two liposuction treatments she underwent in effort to correct it. “I have incisions all over my body. I have had stitches, I have worn compression garments under my chin, I’ve had my entire body tightly girdled for eight weeks — nothing helped,” she said.

“Those CoolSculpting commercials were on all the time, on CNN, on MSNBC, over and over, and they would ask, ‘Do you like what you see in the mirror?’ They were speaking to me. It was about stubborn fat in areas that wouldn’t budge. It said no downtime, no surgery and… I drank the magic potion, and I would because I’m a little vain,” said Linda, a woman who had spent her life being hugely rewarded for being a little vain. “So I went for it — and it backfired.”

Linda’s return to fashion has been bittersweet. “I miss my work so much, but honestly, what can I do? It isn’t going to be easy,” she told British Vogue. “You’re not going to see me in a swimsuit, that’s for sure. It’s going to be difficult to find jobs with things protruding from me; without retouching, or squeezing into things, or taping things or compressing or tricking…”

She wanted readers to know that her face was taped by makeup artist Pat McGrath for the photo shoot — which would turn out to be the big headline from the cover release, splashed across the webpages of the Daily Mail and Yahoo. The public still loves that kind of story, just as it did derision of her platinum hair 30 years ago. Linda was open about what it took for her to feel like she could re-enter the fashion world in this way, with this kind of cover. “…I’m trying to love myself as I am, but for the photos…“ she said, “Look, for photos I always think we’re here to create fantasies. We’re creating dreams. I think it’s allowed. Also, all my insecurities are taken care of in these pictures, so I got to do what I love to do.”

If you haven’t yet, subscribe to Back Row to support independent fashion and culture journalism.

A legend in every decade, forever and ever❤️

Thank you for telling this story. I worshiped the supers, altthough my favorite was Christy Turlington. I still see beauty in Evangelista's "maimed" face. She still looks better than A lot of us do, but we have never had her power and her reach. Nor have we had her inner demons.