Store Review: Victoria's Secret

Most women have no idea the company has rebranded. I went to the mall to find out why that might be.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row! If you like this newsletter and are a free subscriber, I encourage you to upgrade to a paid subscription for $50 a year or $5 a month. Paid subscribers get access to this article in full and the complete Back Row archive. They also get two Back Row posts a week and the ability to comment. Beginning this September, paid subscribers will also receive bonus recaps and analysis of fashion week.

“Victoria’s Secret spent the last year trying to shift from a brand associated with the male gaze to a company representing female empowerment,” read a recent Wall Street Journal story. “Many customers don’t know it made any changes at all.”

I found these words surprising. The brand has been on a self-flagellation promotional tour for around a year now, which is pretty remarkable for a profit-driven American company. This is not to say that Victoria’s Secret didn’t do bad stuff. Their “Angels” marketing, a heteronormative, soulless, sparkly visual manifestation of the word “sexy” that looked like it could have only been concocted by a man like former CMO Ed Razek in the middle of the brand’s Ohio HQ, may have sold landfills’ worth of five-for-$32 panties each year for many years. But it also created body image issues for a good portion of an entire generation of women whose household seemed to always possess, through no fault of their own, a VS catalog. It also employed models like Erin Heatherton, who resorted to taking diet pills and injecting herself with HCG to stay thin enough to keep her contract. And it led to a company culture that was misogynist, fattist, and transphobic.

Related: Read my 2018 TIME feature: Victoria's Secret Created an Impossible Ideal of Sexy. Now It's Struggling to Stay Relevant

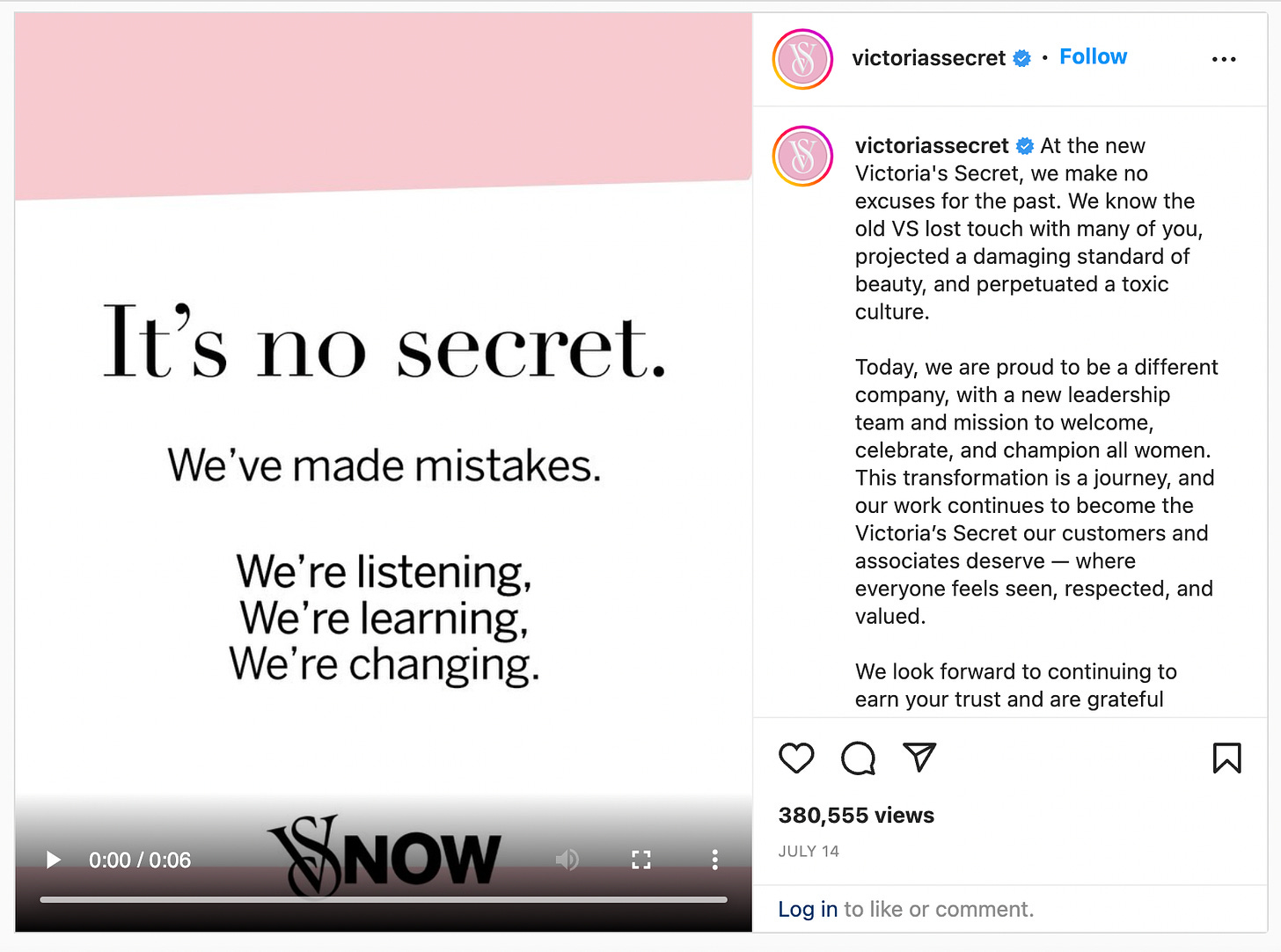

Often when corporations fuck up — and fuck up so badly that they really have to acknowledge it publicly — the first step is to issue the driest, most dispassionate version of an apology that the legal and PR teams can possibly agree upon. The second step is to immediately go back to acting like everything is dandy and the fuckup never happened. Instead, Victoria’s Secret has been braising in its unpleasant past, re-living its own mistakes over and over again, season to season, in a bizarrely public fashion. When it announced its rebrand last summer, they did so via the “VS Collective,” a group of contracted spokesmodels including women like Megan Rapinoe, who were paid to tell the New York Times that Victoria’s Secret had been “patriarchal” and “sexist.” The latest ads for Victoria’s Secret even state, “It’s no secret. We’ve made mistakes.”

If this ad gives you bad vibes that may be because these promises to listen, learn, and change are also the text messages of someone stored in your phone as “DON’T ANSWER.”

As if all of this weren’t enough, the company then forked over “internal research documents” to the Wall Street Journal, which showed that most shoppers “weren’t able to identify Victoria’s Secret & Co. as the brand behind recent ads of models wearing its lingerie.”

The ads show women with different ethnicities, body types and ages mostly in natural-looking lingerie, including a pregnant Grace Elizabeth and multiracial model Paloma Elsesser.

When asked about it, focus group participants agreed that diverse, inclusive marketing was indeed what the brand should be doing. Post-downfall CEO Martin Waters was offered up for an interview, and told the Journal, “You don’t change a brand’s positioning in five minutes or a day or a month or a week… It takes years.”

I realize that I live in a bubble as someone who receives a daily Victoria’s Secret email news alert. Even so, given all the press about its downfall and new direction, it surprised me that so many women had no idea that VS was making such a big deal about not being into its old games, like sending models who had barely eaten for weeks in preparation of the fashion show down glitter runways for national television cameras wearing little more than thongs, padded bras, and 60 pounds of “wings.” I figured the only way that women with a much more average interest in Victoria’s Secret would be in the dark about its new direction would be if its stores looked and felt the same. My suspicions were confirmed when I went to my local mall to experience Victoria’s Secret for myself as a shopper.

A distinct syrupy vanilla fragrance kicked up around Lush, carried over to Bath & Body Works, and just about lifted a few storefronts down around Cole Haan. Across way blared Victoria’s Secret’s pink-striped facade that looked just as it did in my nineties and aughts youth. Nothing about those pink stripes says “new decade, new me.” Its second problem is the signage. Victoria’s Secret is the one of the few brands so much as flirting with high fashion to retain a serif logo, which may be the only cultural artifact from 18 years ago that fashion brands can’t abandon fast enough.

Like the vanilla gas emanating from Bath & Body Works, the pink stripe motif is overpowering, making it easy to miss the videos playing within it of Victoria’s Secret’s new diverse models. Yet on the opposite side of the entrance from one of those videos was new spokesmodel Hailey Bieber, and the text, “Introducing the very sexy SO OBSESSED wireless push-up bra.” If you're wondering how Bieber fits in here it’s because VS would hate to exclude anyone, even society’s least excluded women.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Back Row to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.