Discover more from Back Row

Karl Lagerfeld's Biographer on His Fascinating Life and Complicated Legacy

A new book reveals surprising details about one of fashion's most celebrated figures.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. Today’s issue concerns a topic dear to my heart — fashion biography! — and is free to read. If you want to support more journalism like this, become a paying subscriber for $50 annually or $5 a month. Paid subscribers get two full Back Row posts per week, plus access to commenting and the complete archive.

You can also support Back Row by sharing these stories on social media with a link.

With great cultural influence comes controversy. I struggle to think of a cultural icon, from Anna Wintour to Steve Jobs, that has escaped public debate about the merits of their work in the face of their faults and mistakes. Karl Lagerfeld, one of the most influential fashion designers of the last century, is one such figure.

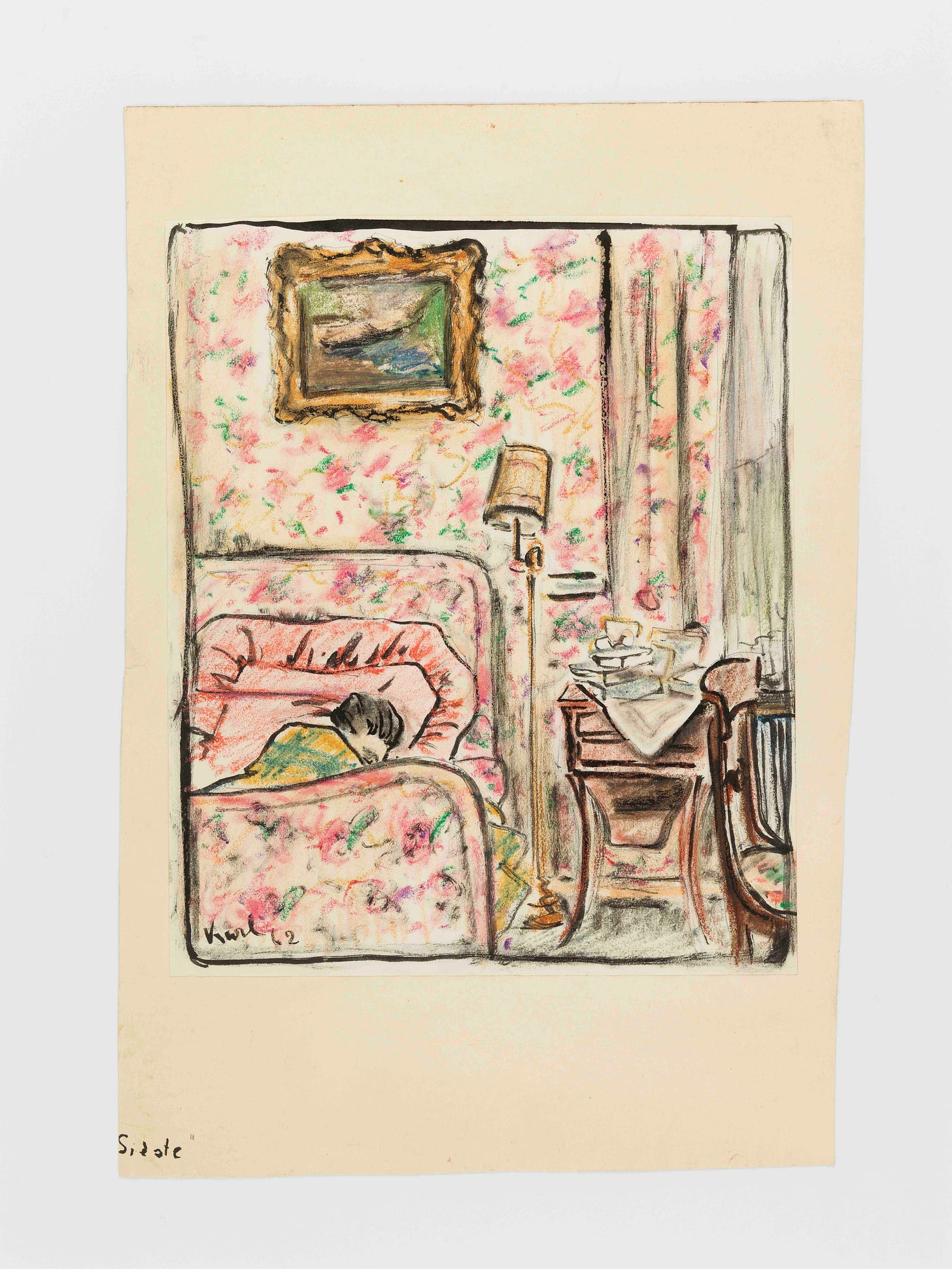

A new biography, Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld by William Middleton, takes readers on a page-turning journey through an existence that is dazzlingly glamorous, occasionally devastating, and, probably to many of us, simply exhausting-sounding. In the early nineties, Karl oversaw around fifteen collections per year for Chanel, Fendi, and his namesake brand, plus a vast fragrance business doing $100 million in revenue. He also published books, photographed his own ad campaigns, and obsessively decorated his homes.

Karl understood, from his earliest days in fashion, how to work the media. After moving to Paris from his hometown of Hamburg, Germany, he won the Woolmark Prize in 1954 for a coat design. In a letter to his mother, he described being on stage, where he had to answer questions: “Some said afterwards that it was as though I was used to being in the spotlight.” At a reception following the awards, Pierre Balmain (who later hired him) complimented Karl on his tie. Karl wrote to his mother, “Was it tasteful, I don’t know. But it was noticed and that is the only thing that matters to me. I don’t care what people say as long as they say something.”

His public persona was very much cultivated through soundbites. “I hate rich people who live below their means,” he once said. And another time: “I love revenge.” (He knew, Middleton explains, that “public breakups... made for good copy.”) The title of Middleton’s book comes from the Karl quote, “I don’t care about posterity. Just don’t care! It won’t do anything for me. It’s today that counts: paradise now!” Karl’s quotes precede many chapters, such as the one about him starting at Chanel in 1983, when he was 49: “Respect is not creative. Chanel is an institution, and you have to treat an institution like a whore — then you get something out of her. Now we begin!”

In an interview with Numéro in 2018, Karl made a number of wildly offensive remarks. Asked whom he’d rather be stranded with on a desert island, Virgil Abloh, Jacquemus, or Jonathan Anderson, he said, “I’d kill myself first.” He also decried the #MeToo movement, saying, “If you don’t want to have your panties grabbed, then don’t become a model.” In other interviews, he disparaged fat women and Syrian refugees.

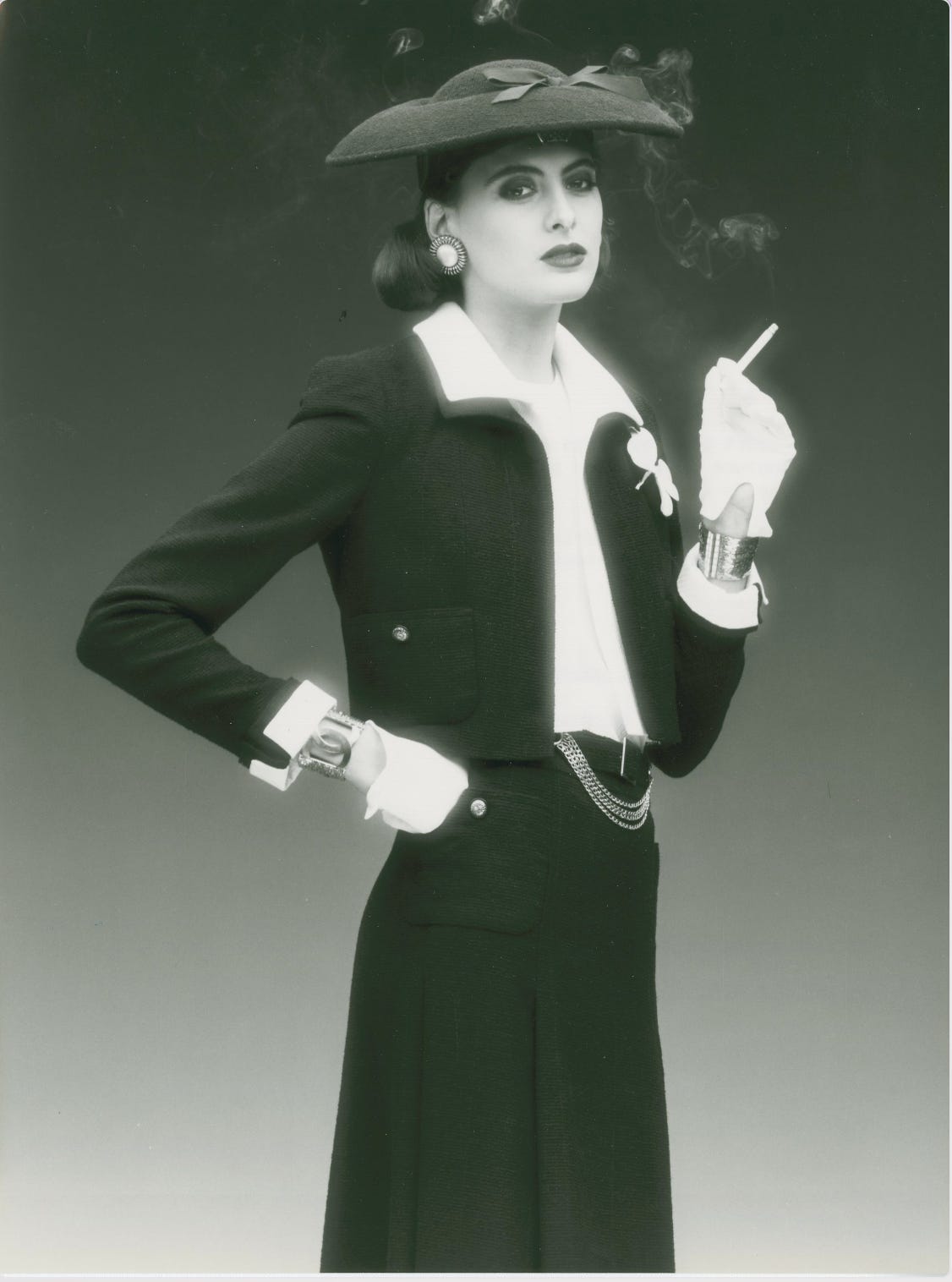

These comments are receiving renewed scrutiny in the run up to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute exhibition on Karl, which will be opened by a Karl-themed Met Gala in May. But Middleton thinks there’s so much more to Karl than offensive statements. Many of Karl’s friends and former colleagues, including his Chanel successor Virginie Viard and his cat Choupette’s self-described nanny Françoise Caçote, spoke only admiringly of him. Karl also changed the fashion business — by turning fashion shows into spectacles, by mixing luxury with mass market brands, and by crafting a public image that elevated him from designer to celebrity regarded by many as almost godlike. Middleton also shares new details about Karl’s childhood in Germany at the start of World War II and the prostate cancer that ultimately led to his death in February 2019. I came away from the book more certain than ever that there will never be another figure like Karl.

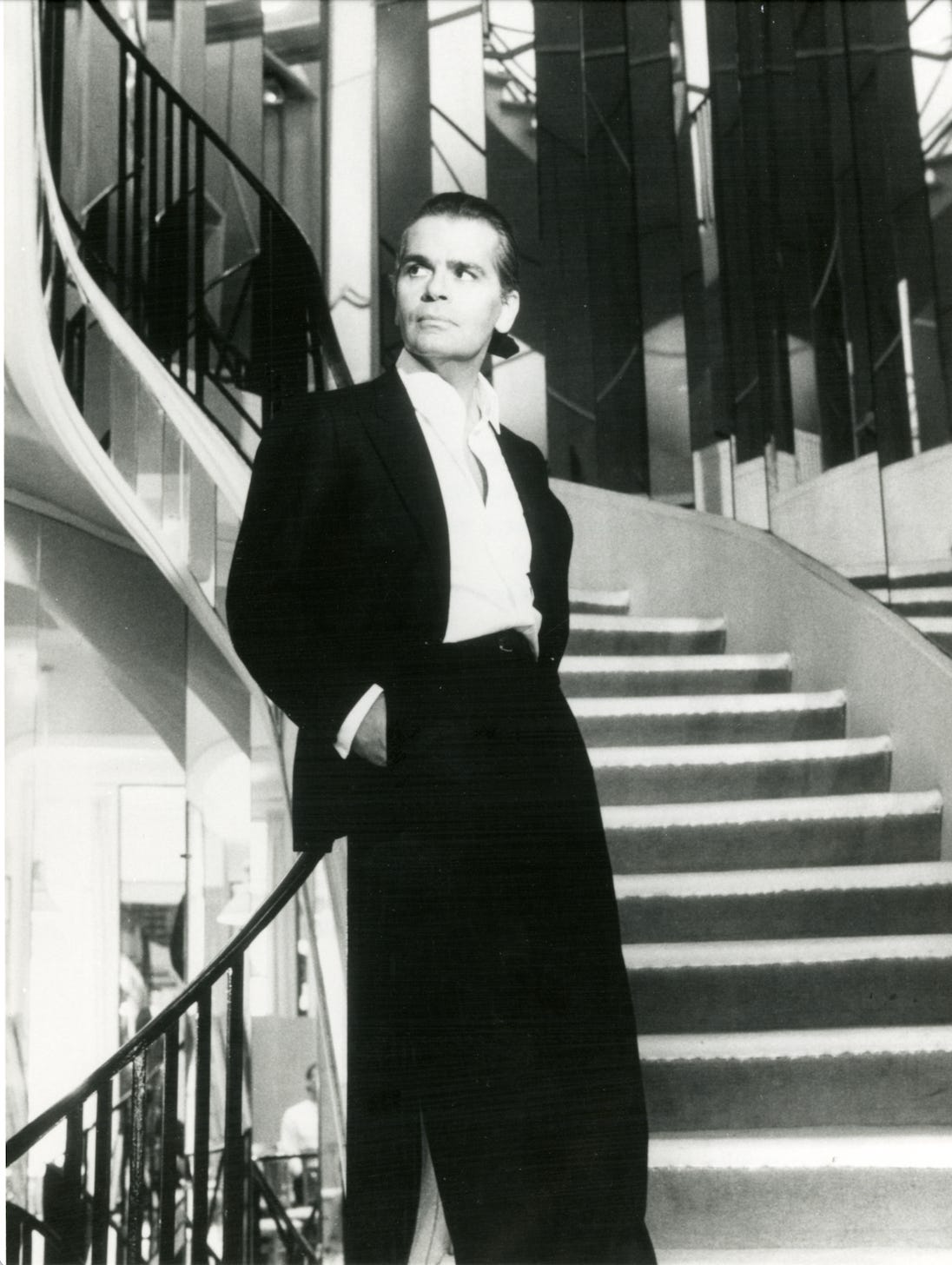

Middleton moved to Paris in 1990, becoming Paris bureau chief for Women’s Wear Daily and W in 1993. In this job, he covered Karl regularly and got to know him. I spoke to Middleton by Zoom recently about his book and Karl’s legacy. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

I was struck by how, when Karl started working in fashion in the fifties and then through the sixties and seventies, everything just seemed so much more fun and less corporate than it is now.

It was so all-hands-on-deck. Like, Karl was backstage putting accessories on models right before they went out. It was all very kind of freewheeling and personal. But so much of the corporate concentration of power in fashion happened starting in the nineties with the formation of LVMH and [Kering]. Like Chloé, when Karl was there in the nineties, his studio was above the shop on the Rue de Faubourg St. Honoré. Now it's a whole huge corporate building with a separate building for archives.

And Karl thrived in both worlds, which I don’t think many people would. Your book notes that his sales were a point of pride for him.

Karl was blamed a lot of times for the accelerating pace of fashion and all of the shows, and I think it's unfair. I think Karl was adapting to what fashion was becoming. It's true that he decided to make the cruise shows [Chanel’s Métiers d’Art collections] more of an event than they had ever been before. In the nineties, cruise shows were something that they did in the showroom with house models. But again, he's just reflecting, I think, what fashion was at that point.

Karl was never forthcoming about what his childhood was really like, but you uncovered a lot of new details. Why did he lie about his birth year?

I always knew that he shaved five years off of his age. I assumed that that was about wanting to be younger. But Gerhard Steidl, who worked with him for decades, a major art book and photography book publisher in Germany, said, “I asked him, ‘Why do you say you were born in 1938 when you were really born in 1933?’ And he said, ‘I was ashamed that I was born in the same year that the Nazis began their destruction of the Jewish people in Germany. And I didn't want to be associated with that.’”

If you were born in 1938, you don't really remember World War II; if you're born in 1933, you do. Karl rarely spoke about World War II, and he gave the impression that he didn't really remember anything until this interview he gave the summer before he died. And then he admitted that he did recall the bombing of Hamburg.

How do you think that affected him as a child? This was when he became interested in the French eighteenth century.

I think that creators respond in different ways to hardship like that. Gerhard Richter, the German artist, saw the bombing of Dresden when he was a kid and was so struck by that, he incorporated that into his work – these images of planes and bombs and Nazi soldiers. And Karl did the opposite. Here he is in the middle of one of the darkest moments in history, and he suddenly is introduced to this world, he doesn't even know what it is. But it turns out that it's the French eighteenth century, and if you're a sensitive, creative person in the middle of all this destruction, and then suddenly you find this incredible, glittering, sophisticated world, of course you're going to be interested in it. It becomes a lifelong fascination for him.

What were his parents like?

His father was much older, and very involved in business [as an importer-exporter], and so he was somewhat distant. The mother is a really interesting figure, because to be honest, I feel like for me, she's not completely in focus. I quote someone saying that she was like an ice pick, and then someone else that said that she just kind of floated through the background of [Karl’s] apartment, you didn't speak to her when she went by. I know what Karl said about her all of his life. He tells these amazing stories. Sometimes I think, are they almost too good to be true? Because the voice almost sounds like Karl. Or is it just that Karl's voice reflects what his mother's voice was?

You report in the book that his mother joined the Nazi party.

I have to give credit to Alfons Kaiser, a German journalist who wrote a biography on Karl. He uncovered that information. He also found a photograph of a Nazi flag flying in front of her house.

In a dictatorship, everyone has to toe the party line. Karl's father was the head of a major industrial concern, and so you certainly have to give the impression that you adhere to the Nazi party. To me, that's not very surprising.

But what was most surprising about her is that after the war, she wrote a text where she explained her membership in the Nazi party. At the beginning she felt that it was restoring strength to Germany. And then when it became clear to her what was being done to the Jewish population in Hamburg, she was horrified. But what she did in this text was not excuse her behavior. She sort of admitted that she was a member and tried to explain where that came from, and then said that she changed afterwards. So, Alfons Kaiser felt like she was more frank about her involvement and more eager to accept criticism than many people in Germany who just pretended not to be involved at all, or would not talk about that moment at all.

You write that what brought Karl to fashion was a Christian Dior show he saw in Hamburg in 1949.

In 1949, two years after the New Look, Christian Dior comes to Hamburg to do a fashion show, and it's in the hotel where Karl and his parents happen to be living while they're finishing a new house in Hamburg. Karl goes down to the show. I've seen some images of that show and it must have been extraordinary for a teenage boy in bombed-out Germany to see the luxuriousness of this Paris fashion in these salons, in this hotel. That decided his direction — that he wanted to go to Paris and become a fashion designer.

What does it say to you that someone like Karl, whose image was so carefully crafted from the moment he stepped on that stage in Paris to accept the Woolmark Prize, became so successful in fashion?

I think that he earned that. When I first knew Karl in the nineties, my feeling was, to be honest, that there were others who were more important in terms of fashion, but that Karl was so important in terms of the culture. He knew everything about art and cinema and music. But the more research I did for this book — and I'm not a fashion critic, I'm not a fashion writer, I've worked for two fashion magazines in my career — I don't concede that there are others who were more important in terms of fashion. Karl was very important in terms of fashion before he even started at Chanel [in 1983], and then what he did at Chanel was incredibly, incredibly significant. No one had ever taken a an important, historic house that was practically bankrupt and completely revitalized it.

What were some of his most important impacts on fashion?

There's a quote that I found from an interview in 1974, I believe, where he said something like, “Genius is knowing what to make of what's out there right now, I practice vampirism to the Nth degree.”

I mention this in the book, but I think It’s super-interesting: he was going up in the elevator at Chanel, and he came across someone who worked there who was very attractive, and he complimented her. And she said that the bag was Chanel, but the coat was H&M, because she couldn't afford a Chanel coat. So Karl knew that this H&M thing was in his world, right? And so when someone came to him to do H&M [the Karl Lagerfeld for H&M line that came out in 2004], he said, “Absolutely.” Then at the end of that phone call, he said, “One other question.” The guy thinks he's going to ask for 10 million euros or something crazy. And he's like, “Have you asked anyone else to do this?” And he's like, “No, you're the first.” And he was like, “OK, great. That's what I want.”

Karl’s offensive remarks are getting a lot of attention leading up to the Met Gala honoring him. You write in the book about how people were outraged after he put “shaped to be raped” in the Fendi show notes in 1984, when he was showing a body conscious collection. (The book reads, “Karl had the idea from a line in French, formée pour être désirée, or ‘shaped to be desired.’ As Carla Fendi explained, ‘Then he said, “Shaped to be raped,” and it rhymed so well in English that we all laughed. He likes to shock a little but he really didn’t mean to offend anyone.’”)

It was in the show notes — shaped to be raped — and nothing happened. And then a week later or 10 days later, it was picked up by the English press and it became a big controversy. Fendi had to step in and explain what the joke was, that it was based on a phrase in French that was not as harsh. They had to apologize and say that it wasn't meant to be offensive. Karl knew just what to do to keep people interested, get people excited. That worked most of the time. And there were times where it went too far.

[Jameela Jamil] has been really harsh about what he said about people being overweight. And I've thought about that a lot, and if she was someone who I could speak to, I would urge her to look at a book like this and to read about the life and to see those comments in the context of a life of a person who lived for 85 years and who worked for over six decades. And see how important she thinks those comments are in context of the rest of the life. And if she's still as offended, then that's certainly her choice. But I think that when you look at what Karl did throughout his life, those comments are not super significant.

I'm not excusing him for his behavior. I'm not saying that it's understandable. I do think that he went too far. But I think that when you look at it in the context of everything else that he did, I don't think those are super important.

So you don’t think those comments should overshadow his legacy?

I don’t think so.

Do you think Karl had real friendships? I got the impression — and I’m not sure if you intended for this to be the case — that after his lover Jacques de Bascher died, he had enormous success but his life was also sort of empty.

Some people feel that. Personally, I don't. That's why I like the little Choupette chapter. I feel like when you have a pet, you do kind of open up and there is a kind of warmth that you have. And I think that Choupette was kind of the most significant relationship that Karl had since Jacques de Bascher. And that makes Choupette more interesting, not just the silly kind of over-the-top cat thing. I found the whole story with Choupette to be more moving than I expected.

Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld is out now.

You made it to the end of this story! You must be enjoying yourself. Why not subscribe for even more of that very same enjoyment? The Milan Fashion Week recap is coming out soon and you won’t want to miss it.

I'm of several minds re: Karl's fat comments.

One: the high fashion industry is for the thin, we all know this, there are manny designers/editors who feel the same way and either haven't made public comments or their comments didn't get the same amount of press as Karl. We've all lived through women's magazines promoting quickie diets, "nothing tastes as good as thin feels", women being called Social X Rays, etc.

Two: Karl himself went through a heavy phase for years, and famously said he dieted to fit into Hedi Slimane's skinny Dior menswear. He famously wrote a diet book, and had a Diet Coke deal as well. His disgust at heaviness could have been partly self loathing.

Three: Karl being so obsessed with art, probably thought of his designs as art and didn't like 'real' women messing up his vision of art. The women Karl knew probably felt the same, and kept themselves thin so their clothes would look their best.

But when it comes down to it, if a larger woman wanted to order Chanel Couture in a larger size, they would sell it to her. And Chanel in the US, at least in the late 90s was definitely available in a size 14-16 (which isn't plus sizes, but definitely more than a 0 or 2.

Great interview!