Discover more from Back Row

Finding Fame, Burning Out, and Leaving It All Behind

Words of wisdom on aging, retirement, and so much more from Lyn Slater, who became a fashion influencer and model in her sixties.

Before the pandemic, Lyn Slater went viral for becoming a fashion icon in her sixties.

Sites like BuzzFeed and BoredPanda ran stories about her titled “This Beautiful 63-Year Old Professor Accidentally Became A Fashion Icon And I'm Here For It” and “Journalists Accidentally Confuse A 63-Year-Old Teacher With A Fashion Icon And It Ends Up Changing Her Life.” These stories presented her as a fabulous unicorn eschewing conventions of old age, when, in fact, she had never really thought about her age. And, in fact, she had always dressed the way she was dressing, in Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons, with exaggerated sleeves and clever layers that looked professionally styled. Slater wasn’t seeking fame — all she had been trying to do was play with fashion and write about it on her blog Accidental Icon as a creative outlet. She was working full-time as a professor of social work at Fordham University and this was her hobby. Yet her Instagram following exploded and she became a star.

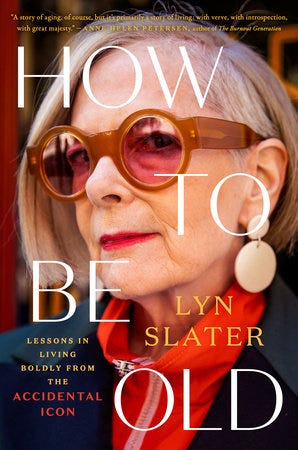

But still, Slater had eschewed the conventions of her age. In her new book How to Be Old: Lessons in Living Boldly from the Accidental Icon, she documents how she turned her fashion hobby into a lucrative career as an Instagram influencer. After she answered a casting call for Valentino and ended up being photographed for an eyewear campaign, for which the brand paid her just $1,550, she landed an agent who told her she should have earned $50,000 for that very job.

Slater traveled the world and racked up sponsorships, but after a few years, she found herself burnt out. She writes in her book:

Although I’m churning out content and making money, it somehow provides no comfort or satisfaction. I’ve overstructured and overscheduled my day with apps that are supposed to help me achieve my life goals, but in reality, keeping up with all they are asking me to do or listen to is more exhausting than helpful. I’m running around attending every event and meeting I’m invited to, without thinking for a moment why I should.

Her book is a lovely, fast-paced, inspiring read. Slater and I had a wonderful, wide-ranging conversation about burnout, aging, inclusion in the fashion industry, and titans like Anna Wintour who put off retirement. You can also find her on Substack

.Can you talk about the career you had in social work before you landed in fashion?

My first master’s was in criminal justice. I was working in a institution for delinquent girls, a locked facility. I began to hear all the stories of the girls. It was the mid-seventies, things like sexual abuse and trauma were not on anybody's radar. And so I really began to feel very strongly that this was not a criminal justice issue, that it was much more about trauma and abuse and poverty and a lot of other things, which led me to see social work as a much better lens to view their situation. I moved to New York City and I was the director of a 20-bed residential treatment center for adolescent girls in the same situation. And I started, through my advocacy for them, working with lawyers in order to get them what they needed. And I then jumped to a law firm, I became head of their sexual abuse project. Through my work there, I decided to go and get my PhD in social welfare, and I was recruited by Fordham University in 2000 to help them develop an interdisciplinary program with their school of law and school and social work. That’s what I was doing in 2014 when I started Accidental Icon.

What surprised you about working in the fashion industry versus being someone who simply enjoyed fashion?

When I first started, it was really fun and exciting because I was working mainly with emerging designers, fashion students. I did a lot with independent fashion magazines, and I was working with these really creative and visionary stylists. I think when I transitioned into Instagram influencing, it became clear to me that fashion was about business. I had been a little bit naïve in the early years thinking it's about art and creativity.

When you look at people like Alexander McQueen and John Galliano in the early days, they were like that very much. I remember there was a Prada show, and it really was a bunch of traveling women, and they had compasses hanging from their belts. I couldn't afford Prada, but I used consignment store clothes and dressed myself as my vision of a traveling woman. That's how I was relating to fashion until I started to see that it's a business.

When I read about Galliano and McQueen’s early days, or even Karl Lagerfeld’s, I’m always struck by how freewheeling and spontaneous and fun the industry used to seem. That said, it always had that coldness of “I’m in, you’re out,” which somehow has become more pronounced in a this numbers-driven world you describe.

They're run by conglomerates now, so you have to factor that in. Then you have to look at those photos of who's running those conglomerates. And you have this movement to make fashion inclusive, which is very superficially being done.

People say, “Aren't you excited about these older women on the runway?” And I'm like, no, because they're tall, thin, white women who are still carrying the standards of youth and beauty into their old age. I guess I don't expect fashion to be inclusive. I don't expect to see a runway show where I'm going to see myself.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. To support the independent culture and fashion journalism you read here, become a subscriber.

Your story about the Valentino campaign struck me as just one more example of fashion saying it wants to be “inclusive” and then not being that by taking advantage of a model like you, in your sixties, paying you a fraction of what you should have earned.

I do have to take some responsibility for being clueless. I didn't read the release form, I just signed it because I was having fun and an interesting experience. But also, I had no idea that you could make money in this fashion blogging thing that I was doing. So yeah, of course I was taken advantage of, but it was sort of, again, walking into a crowded subway with your purse gaping open and your wallet showing.

I taught full time until 2019. So in these early years, it wasn't like I had to make a living from this.

In the book you write, “I stopped being a unique person and became a brand.” You say this in the context of the dissatisfaction you were feeling despite all your success as a blogger and influencer. I would just love for you to explain that feeling.

As long as I was still teaching full time, I really was pretty much planted in the real world. And once I retired to do Accidental Icon full time, number one, my safety net was gone. And number two, the blog became less important, I wrote on it way less frequently. It was almost like I just started living in Instagram, so I was on the app constantly. I was really preoccupied about having enough money to support myself, starting to be very concerned about retirement. As a social worker, I didn't save a whole lot because I wasn’t paid a whole lot.

Everything I did began to be dictated by forces outside of me. It was not me being creative and saying, This is what I'm going to wear and this is how I'm going to wear it. It began as getting briefs [from brands]. Here are the photos we're looking for. Here's what we want you to say in the caption. Here are the hashtags. You start feeling like a can of soup — someone made the label for you and somebody is dictating what you can say. And I just began to lose every ounce of my creativity and my autonomy.

In my early days, I write in the book about how if an editor told me to wear something and I didn't want to, I would say no. But in this phase, I was not saying no to anything. I wasn't even doing fashion [sponsorships] anymore. I stopped being who I was, and it just became about products.

I really liked how you articulated what online burnout feels like. That's something I’ve experienced, along with, I imagine, a lot of other people who read this newsletter, who work in an industry where they have to be — or feel like they have to be — on social media. And then our lives become sort of ruled by our phones, even if it's a passive thing where you don't even realize you're picking up your phone and interrupting whatever you’re doing in the real world. It doesn't feel good to live like that.

When I started to dig in and do research to really look at what had happened to me and why, you see things like, you pick up your phone [144 times a day and spend four hours and 25 minutes on it on average every day]. People my own age didn't comprehend or empathize with what had happened to me. And so when I read

’s BuzzFeed essay “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” I was like like, Oh my God, she's talking about how I feel in a way that most of my peers have not experienced. As a social worker, I'd always had periods of burnout, but this was very different.Was it more intense?

The part where you were burnt out by the very system you were working in was similar. But on an individual level, you could sort of get away from it in a way that I couldn't as this Instagram influencer who was constantly having to check followers and impressions. Your texts never stop, you've got emails coming in every moment, and people want an answer right now even if it's nine o'clock at night. It's much more endless because of technology.

When I was getting burnt out [as a social worker], at least there was something that you could attack or resist. Or you could try to change a policy. In social media, it's an invisible algorithm, so there's no way to confront it. You can’t change it.

I want to talk about aging, too. I feel almost weird asking you about it just because I feel like we never ask men about aging yet women like yourself (and unlike yourself) are called upon to talk about it all the time.

We're at an interesting moment with discourse around aging. The New York Times Magazine just ran a great interview with Isabella Rossellini about aging. Julia Louis-Dreyfus was just talking to the Times, too, about how her podcast is all about hearing from older women. I have personally enjoyed seeing these voices, yours included, proliferate.

At the same time, we have Kim Kardashian telling the same newspaper that she would probably eat literal shit if it would make her look younger, and stories about “Sephora tweens” starting expensive skincare regimens, which of course at their heart are all about preventing signs of aging. I wonder what you make of all this.

My concern right now is that we have two very polarized views of aging. Even people like Isabella Rossellini and Julia Louis-Dreyfus and whom she chooses to have on her podcast — these are all quite privileged women in terms of being highly resourced. So I feel like we have these two poles about aging. One is the decline narrative, where you're going to be disabled, you're going to have dementia, you're going to be a burden on your family — you are ruining it for every generation behind you, and you're blood-sucking society, pretty much. On the other hand, you have these new creatures who are pretty ageless. They're hot, they're fit, they're running marathons at 90, they don't need anybody.

Neither of those two poles represent the majority of what aging is really like. There are a lot of young women writers like yourself,

, , who are blowing up motherhood and blowing up divorce and blowing up youth and beauty standards, and they're being very brave about the good and the bad of it. And I think as older women, they need to hear from us the good and bad of it.Policy people are looking at the ageless wonder and saying, they don't need support, when most of the people in the middle are not rich enough to have everything they need, but they're not poor enough to get support.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. To support the independent culture and fashion journalism you read here, become a subscriber.

I’m nearing 40 and have been thinking more and more about the whole idea of midlife crises. Did you ever experience one?

I've always had changes at different periods of my life because I don't want to be bored. I never attached age to it. I went and got a PhD right after I went through menopause, so I think probably you could call it a crisis, but I wasn't experiencing it that way. I didn't stress out about being 40. It was only after I did Accidental Icon and people kept telling me I was old that I started to think about age.

I wasn't doing it as an anti-aging project. It was, I'm bored. I think fashion could be cool to look into, and I’m going to fling myself into it and have fun and figure it out. Then the media would be like, “Look, she loves fashion even though she's 62.” “She’s good at social media even though she’s 64.” I just wonder if we would even think about it so much if people didn't make such a big deal about evaluating yourself at different ages, which then ironically creates stress, which we now know through research is going to put you at higher risk for cardiovascular incidents that could take years off your life.

I think for a lot of women, the late thirties is a difficult phase of life, because many of us are having kids while juggling demanding jobs.

My daughter is your age. She has two kids. She has a full-time, very demanding job. You're doing it a little bit later than I did, and your life is going to be consumed with that probably for more of your forties, because again, you started later. When I was going through all of it, I always wanted to be a writer, I never had time to devote to it. And if I had known in the middle of those days where I'm like, OK, my daughter is sick. I don't have childcare. I have a meeting I can't miss, what do I do? That I would publish a book at the age of 70, I would have been able to calm myself down and say, You might be losing yourself now. This is hard, but you are going to get through it. There will be time for you.

I also want to talk about retirement. I think about this quite a bit partly because I wrote a biography of Anna Wintour who turns 75 in November and hasn’t retired. But also, because we're in the midst of a sea change in the fashion business, where titans of the industry are retiring or likely will soon. Miuccia Prada is 74 and planning her exit, Ralph Lauren is 84, Michael Kors is 64, Giorgio Armani is 89. Karl Lagerfeld worked until his death. There seems to be a particular reticence in this industry to retire. You’re still working — publishing a book and starting a Substack. How do you think about retirement?

I think the bigger issue, and I'm even looking at our presidential election, is people’s attachment to power. And how much it defines them, keeps them in their power, in my opinion, after they should be sharing it and letting it go. And that's how I see a lot of these people now who are older politicians, people like Anna Wintour. It is about power, and there is an unwillingness to let go of it and to share it.

I feel humiliated for them because I kind of see it as a bit pathetic. There's something so energizing about sharing power with other people. I always loved working with young people because any innovation, older people know the history of the thing, but young people know the now of the thing, and the best new stuff is going to come from the interaction of both. A really important moment for a person in power — and that could be at any age — is when should I step aside and make room? I don't even think it's about retirement. [Anna] could leave her job and do a million, billion creative, fabulous things. But she's choosing to remain in this position of power.

You say that, though, as someone who experienced this world and realized, I see this is what I’m supposed to want, but it’s not actually fulfilling me, and therefore I don’t want it. Or at least, I don’t want it in this way.

I think I got pretty arrogant and I was very cocky about it. Part of it really felt like, I'm walking up to an event and the publicist is putting me at the front of the line, or, I'm sitting in the front row. It's very seductive, so I understand why people get attached.

I think the biggest thing I took away from your book was to have hobbies and learn new things. Having a rich life outside of work and the world of a cell phone really lessens the desire for validation, conscious or not, from fashion and social media.

That’s right. It can’t be your whole identity. That’s when it becomes dangerous.

Get Lyn Slater’s book, How to Be Old, subscribe to her Substack, and follow her on Instagram.

Loose Threads

Shein doubled its profits to $2 billion in 2023, reports the Financial Times. Sales for the period totaled $45 billion. The company, valued at around $60 billion, is planning an IPO. Lawmakers in the US have been hostile to an IPO here owing to the brand’s operations in China; the UK is said to be Shein’s back-up option.

Karlie Kloss took a break from building her media portfolio to visit her home state of Missouri to gather signatures for an abortion ballot referendum there. It’s not the first time she’s taken a public stance on abortion rights. Her advocacy is great to see!

Meanwhile, Rita Ora is launching a hair product line called Typebea which Business of Fashion painstakingly (hilariously) points out is pronounced “Type B.”

The wedge sneaker passes the torch? The Cut reports that the “ballet sneaker” is a thing now.

Mary Katranzou has been appointed the creative director of Bulgari’s leather goods and accessories. It’s a new job, but the brand already sells a whole fleet of $4,000-ish purses.

The celebrities who won Easter are the Beckhams, who celebrated on a yacht.

Is the pandemic embrace of gray hair behind us? I know the Vogue headline “The Best Way to Color Gray Hair” is written for SEO, but still.

Earlier in Back Row:

Subscribe to Back Row

The fashion and culture newsletter that publishes what legacy media can't.

As someone who is 64, I think it's high time that fashion was more age-inclusive (well, inclusive in all aspects, really). I appreciate Lyn's perspectives and her style, but I think it's important to note that you don't have to look like her, or the late great Iris Apfel, or Judith Boyd to be considered stylish over 60. Bold colours, chunky jewelry, etc. is *a* style, not the only style. I feel like there is some confusion out there that says mature women have to look a bit outlandish to be considered stylish. While I appreciate their style, each person can be stylish in their own way. Is that what it's really all about?

Lyn Slater is a luminous person at any age. I want to live my life like that, never letting go of the curiosity and spark! Best. Interview. Ever.