The Women Who Went to Fashion Week Even During War

Today, fashion show attendees complain about having to shuttle around by plane. Eighty years ago, things were much more difficult, to say the least.

In today’s (free) issue:

New York Fashion Week is in dangerous decline — but people have had beef with it since it started.

Think Anna Wintour’s been at Vogue too long? Well, what do you know about Edna Woolman Chase?

Loose Threads, including NYFW highlights and Taylor Swift.

New York’s fashion industry employs almost 50,000 fewer people than it did ten years ago, according to a study from the nonprofit Partnership for New York City. Employment is forecast to continue declining over the next few years, while the fashion industry’s gross city product decreased 13.6 percent from 2012 to 2022.

Timed to New York Fashion Week, which officially began Thursday, the organization warns of the event’s “diminished status,” and how industry leaders will need to take action to maintain the city’s status as a major fashion capital.

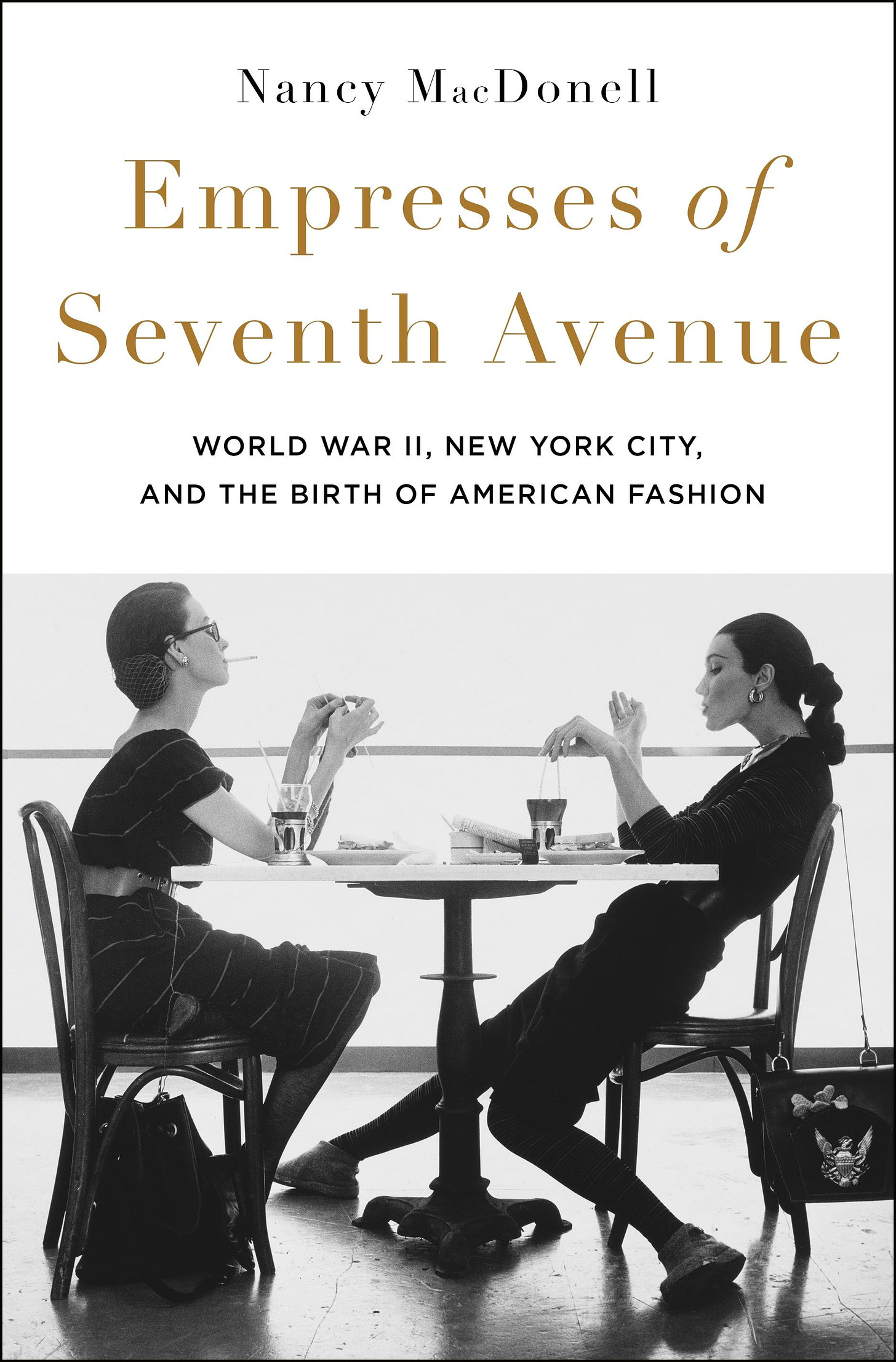

The idea of “fixing [insert aspect of the fashion industry here: fashion week, the fashion system, etc.]” has been a topic of discussion since, well, forever. Fashion historian and journalist Nancy MacDonell recently published Empresses of Seventh Avenue: World War II, New York City, and the Birth of American Fashion, a fascinating new book that documents the struggle of New York’s fashion industry to exist in the first place. “It was entertaining to me as a fashion journalist to read about people going to the very first fashion weeks [in the 1940s], having the same complaints that fashion journalists have now. There are too many shows. There are too many publicity events. The PRs never leave you alone. The clothes have nothing to do with real life,” she said at our talk this week at the Rizzoli bookstore in Manhattan.

I was fascinated to hear from MacDonell how history has repeated itself. In many ways, American fashion can never be what it once was. And in others (editor rivalries, for one), it remains very much the same.

This interview was adapted from our conversation Wednesday night, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you talk about this image on your cover?

This is the January 1st, 1950 issue of Vogue. It's part of the story looking at the previous 50 years in fashion. The photographer is Irving Penn. The two models are Dorian Lee and Mary Jane Russell, both of whom were very well-known at the time. It's a really significant photograph because they're wearing American fashion. Before the fall of Paris, there was really very little American fashion that appeared in American fashion magazines. They chose clothes by Claire McCardell, who was sometimes called the mother of American sportswear.

These were really unusual clothes for the time. It's not the stereotypical idea of the 1940s that we have with the big pompadour and the shoulders and the peep-toe shoes. That's not what Claire McCardell did. It's really like athleisure. They're wearing leggings, they're wearing body suits, and they're wearing little wool jersey dresses over them. When these clothes first came out, Life did a story on them, and the photos were captioned with things like “strange clothes for winter wardrobes.” People just didn't know what to make of this approach to fashion.

Given her influence, why do you think McCardell’s not so well-known? A lot of people who know who Coco Chanel is probably wouldn’t know who she was.

Well, the French are very good myth makers. Claire McCardell got cancer and died young [at 52]. Coco Chanel was much older [87].

One designer you highlight, Elizabeth Hawes, got her start at a “copy house.” Copying of course is considered taboo within the industry today — what were attitudes at the time?

She went to Vassar. She studied economics. She accompanied her classmate to Paris. She was ordering her trousseau, but Elizabeth Hawes was not there for that. She was there to learn how to be a designer. So her friend's mother got her this job at a copy house. These existed really on the fringes of the haute couture industry. Everyone knew about them, but if they were ever, say, raided by the police, they could be shut down. They would attain models by various illegal means of actual dresses from the couture houses, and they would copy them down to every last detail. She was this innocent little 21-year-old suddenly working for a criminal enterprise. Mainly what she did was sketching. When these dresses turned up in the couture house in various ways, perhaps one of the seamstresses who worked in the couture house might smuggle out a pattern, take it there, it would be copied, bring it back.

[In her next job] for a New York manufacturer, she started illegally sketching fashion shows in Paris. She did this for a couple of seasons until she became absolutely horrified. She never really had any respect for the people that she was working for.

How would she sit in a fashion show and sketch the clothes without anyone seeing?

She couldn't do it in the fashion shows. She would have to memorize all of the details — very, very detailed, like the shape of the buttons, the shape of the neckline, the shape of where all of these seams would go. Fashion designers today show maybe 40 looks. They were showing 200 or 300 looks at the time. So she was really holding a lot of information in her head. A fashion show could go on for an hour. She would have to wait until she got back to her apartment, and then she would have to make very detailed sketches, essentially blueprints. It was really lucrative. For two weeks work, she would make about $450, which was a lot of money.

Fashion Week starts this week in New York, kicking off fashion month. Editors, influencers, buyers, whoever goes to shows these days like to complain about having to go to New York and then London, Milan, and Paris.

New York used to go last, but they got very tired of being accused of ripping off everyone else. So they started going first.

I thought reading your book, if we think it’s bad now, it required so much more effort in the forties. Can you describe the effort editors underwent to see the shows?

Let's talk about the very last journey they were able to make before the war made that impossible. Americans were able to travel to Paris, as they always did, in January 1940. It was dangerous to cross the North Atlantic, but they did it anyway. They pretty much all traveled on one ship. It could accommodate more than 1,100 passengers. About 160 made the trip because who was going to go to Paris to buy clothes at this point? They actually couldn't go to Paris because that was a belligerent nation. They had to go via Genoa.

They took a train from Genoa to Paris. There was no heat on the train, there were no lights. Because everyone had so much luggage, they couldn't even get to the restrooms. It had been converted from sleepers to daytime cars, and it was filled with soldiers. So it wasn't a very comfortable journey. When they got to the border in the Alps, everyone had to climb out into the snow, have their passports checked, and get back on. They made this journey, they placed their orders, and they just assumed they would be back in August. And then a few months after they finally got back to New York, Paris fell to the Nazis, and they could not do that anymore.

You have a quote in the book from Carmel Snow, who became editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar in 1934: “I was no more willing to conceive the permanent fall of Paris than Charles de Gaulle.”

She absolutely revered Paris. Edna Woolman Chase, the editor-in-chief of Vogue, also revered Paris. Although these were American fashion magazines, there was very little American fashion in them. They were really filled with French fashion and American copies of French fashion. So an inconvenience like a war wasn't going to stop them.

But when they couldn’t go, what happened?

It was a real shock to the system. As Winston Churchill said, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” They took advantage of the fact that the French were temporarily out of the game, and for the first time, they were obliged to design the fall 1940 collections without any input from Paris.

How did that go over?

It went over really well, despite everyone's concerns. Lois Long, who was the fashion critic for the New Yorker, and probably one of the more acerbic fashion writers you'll ever encounter, said naturally there were some horrors because this was the first time it had ever happened. But they pulled it together.

And after the war, what was the new normal the industry reached?

The French came back. If you've seen [the TV show] The New Look, you know how this happened — Christian Dior designed the New Look, and this was really the savior of Paris couture. But American designers, although some of their employers wanted them to go back to copying the French, they were by and large able to resist this. They continued to design what they were really good at, which was sportswear. Clothing that today sounds like we're talking about stuff that you would wear to play sports. It was really referring to more casual clothing. A lot of it was knit-based. It didn't have the really rigid tailoring that you would see coming from Paris. It was clothing that was a marriage of form and function. It was beautiful, but it was also practical. It was in fabrics that you could wash.

Edna Woolman Chase was the longest serving editor-in-chief of Vogue, holding the job for 37 years.

Although Anna’s coming up.

Anna’s been doing it for 36 years, so if she stays through next summer she will surpass her. But much in the manner of more recent history, Chase and Carmel Snow had a rivalry, right?

[Snow] went to work for Vogue in 1921. She was hired by Condé Nast, the person, not the company, and he took her under his wing. She was very charming. He really led her to believe that when Edna Woolman Chase retired, and remember she'd been editor-in-chief since 1914, that Carmel Snow would get the job. About ten years in, she realized this was never going to happen. And she was right — Edna Woolman Chase stayed on in the job until 1952, after starting working at Vogue in 1894 when she was a teenager in the mail room.

So Carmel Snow did the unthinkable. In those days, Vogue and Harper's Bazaar were like the Hatfields and the McCoys. They had an intense rivalry. If you worked at one, you didn't talk to people who worked at the other. If you were a photographer who contributed to Vogue, you certainly would not contribute to Bazaar. So she left. She got an offer from William Randolph Hearst. He said, “I'll bring you to Bazaar, and within a couple of years, you will be the editor-in-chief.” So she left Vogue.

They described it differently in their respective memoirs. Edna Woolman Chase said they had a decorous conversation, although she did express her disapproval. Carmel Snow said she was in the hospital getting over the birth of her third daughter. She said, “They came and they stood around my bed, and it was an absolute harangue. They told me that Vogue made you, and now you're abandoning us. This stain will stay with you forever.” And it kind of did, as far as Vogue was concerned. When Carmel Snow retired, some journalist was writing a story about her and went to Vogue to get a quote. And the quote that they were given was, “To talk about American fashion from the point of view of Carmel Snow is like talking about American history from the point of view of Benedict Arnold.”

Wow.

Yeah, fashion people. We know how to hold a grudge.

Get Empresses of Seventh Avenue here.

Loose Threads

A bunch of celebrities attended Ralph Lauren’s New York Fashion Week show at the Hamptons horse farm he bought two years ago for $16 million, and offered their thoughts on the collection to ABC. Noted fashion commenter Tom Hiddleston’s quote tells you everything you need to know: “It’s an extremely precise and intelligent vision because you sort of think, I’d like to be a part of that. I’d like to live that,” he said. "Very inspiring.”

Lady Gaga is on the cover of October’s Vogue to promote her movie Joker: Folie à Deux, which Vanity Fair called “startlingly dull.” Between other covers this year including Blake Lively, Sienna Miller, and Kendall Jenner, one wonders if the magazine is simply not chasing stars of the moment like Charli XCX and Chappel Roan, or if those celebrities would deem a Vogue shoot off-brand.

Proenza Schouler’s NYFW show included a shoe collab with Sorel. Anyone pinning this??

The salient detail from WWD’s story about its “fantasy front row for the spring 2025 shows” is that “Mormon tradwife TikTok power couple Nara and Lucky Blue Smith” have already attended. “Mormon tradwife TikTok power couple” seems like perfect copy for someone’s tombstone.

Taylor Swift wore a denim corset, jean shorts, and over-the-knee patent leather red boots to watch Travis Kelce play football. I think he is more likely to attend a NYFW show than her at this point, which probably tells you something.

I agree, Travis Kelce IS more likely to attend fashion week than Taylor!

The eidetic memory one would have to possess to precisely copy 200+ looks without taking pictures is truly mind-boggling. Also, I really did like the RL show more than I thought I would.