Discover more from Back Row

The Biggest Fashion Story of 2023

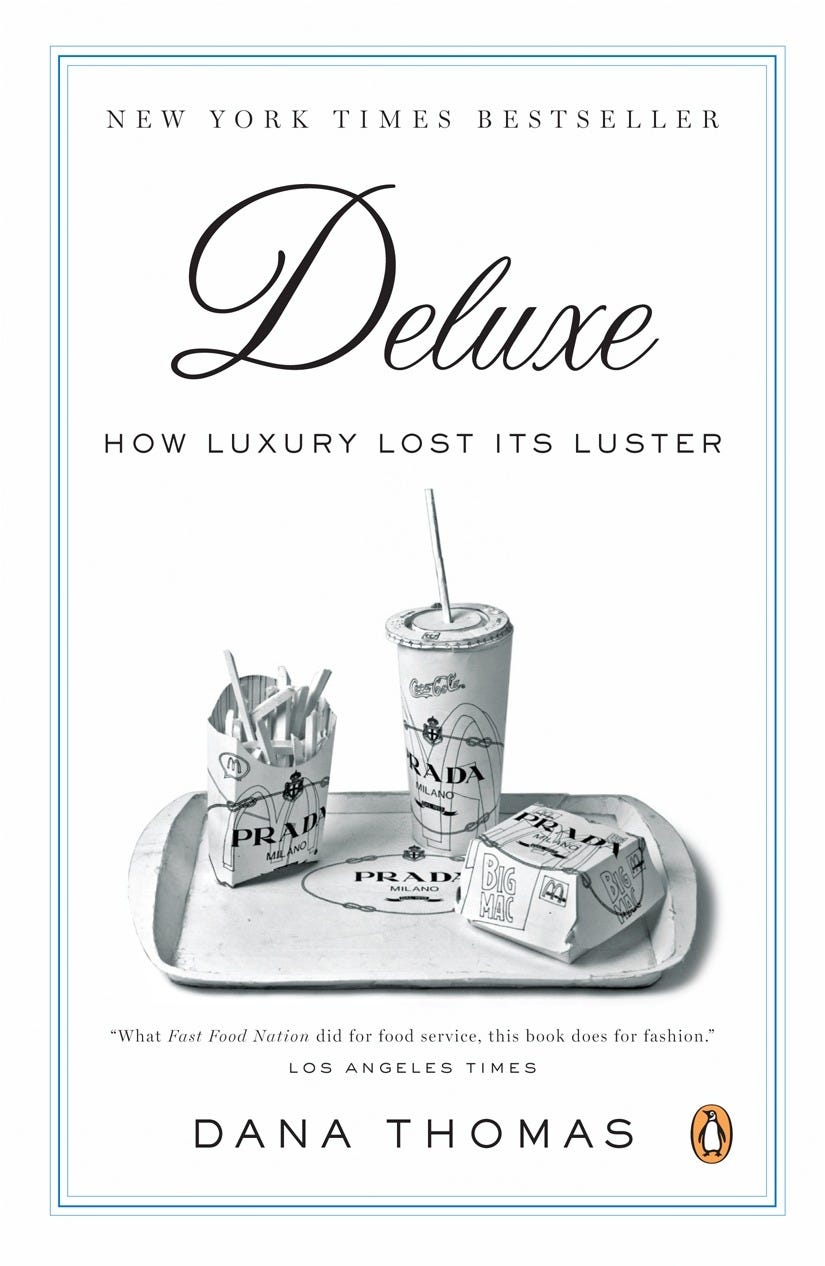

The luxury industry is at an inflection point, says journalist Dana Thomas, who authored the seminal Y2K book on how the industry works, Deluxe.

With 2023 about to end, luxury fashion finds itself at an inflection point. The aspirational shopper is spending less on luxury goods, leaving high-end brands to focus on selling to the ultra-wealthy. While sales grew 15 percent across the luxury sector in 2022, according to estimates from Bain and Company, they are expected to grow around half that in 2023. This led the Wall Street Journal to report recently: “Luxury brands need to find ways to unload their growing pile of unsold stock without reeking of desperation.” MyTheresa told the paper the company was seeing “the worst market conditions since 2008.” We’ve been building up to this moment all year; LVMH CFO Jean-Jacques Guiony had said on an earnings call in July, “The aspirational customer is suffering a bit.”

To make up for the slowed growth of aspirational sales, brands plan to capitalize on their wealthiest customers in a number of ways. One is with jewelry. According to a report from Business of Fashion and McKinsey, the branded fine jewelry market will grow three times faster than the total market from 2019 to 2025, with price points six times higher than unbranded products. Next year, Chanel will open boutiques specifically for top-spending clients. Brands like Bruno Cucinelli are already doing this, and more are sure to follow. “We’re going to invest in very protected boutiques to service clients in a very exclusive way,” Chanel Chief Financial Officer Philippe Blondiaux told Business of Fashion.

In reading all these stories this year, I kept thinking about the book Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster by

(go subscribe to her Substack). First published in 2007, Thomas laid out the economics of the luxury fashion industry, which evolved from small companies that focused on the highest quality product to huge conglomerates, like Kering and LVMH, focused on making as much money as possible. “Disposable income has risen significantly in industrialized nations in the last thirty years,” Thomas wrote in Deluxe. “Both men and women have put off getting married until later in life, freeing them to spend more on themselves. The average consumer is also far more educated and well traveled than a generation ago and has developed a taste for the finer things in life.”She continued, “Corporate tycoons and financiers saw the potential. They bought — or took over — luxury companies from elderly founders or incompetent heirs, turned the houses into brands, and homogenized everything: the stores, the uniforms, the products, even the coffee cups in the meetings. Then they turned their sights on a new target audience: the middle market…”

For anyone hoping to gain an understanding of how fashion operates as a business today, the book remains essential reading, something I still hear regularly referenced by people who work in the industry. I called Thomas, who lives in Paris, to talk to her about what’s changed in fashion since she first published the book, and where she sees the industry going from here.

In thinking about how to sum up 2023 for fashion, there was one really big story, which is the shifting demographic of the luxury fashion customer. Now, the aspirational shopper, which you write about in terrific detail in Deluxe, isn’t buying this stuff as much, leaving brands to appeal to the über-wealthy.

Absolutely. The aspirational customer, as I wrote in Deluxe, is vulnerable to economic shifts and economic turbulence. When there's a recession, they stop buying. When times are good, they start buying. And when they buy, they buy a lot, but they buy small stuff that has big markups.

Now, the big stuff has big markups too, as we've seen with the price hikes of the Chanel 2.55 bag. [A medium classic flap bag saw a 16 percent price increase in 2023, from $8,800 to $10,200.] That Phoebe Philo is selling a coat made in Madagascar for $25,000 is just kind of mind-boggling. Luxury brands aren’t giving up on the aspirational customer, but they're not banking on the aspirational customer anymore, because the wealthy customer made so much money during and after the pandemic.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. To support the independent journalism you read here, become a subscriber.

What do you think that will mean for product assortments?

High jewelry's a big, big business now. The haute couture shows are back to being for clients, as opposed to being noise to sell perfume to the middle-market customer. I have a couture friend who just passed through Paris for fittings on her way to the Dolce & Gabbana Alta Moda show where she probably ordered more haute couture. Brands realized that they can have monster profits and actually produce less, which is the sweet spot, because you're lowering your overhead and raising profits. They've decided that luxury actually should be a luxury again. Their earnings are still going to go through the roof, but that’s because they're charging way, way more for things. I see that even with LVMH owning the Belmond hotel chain — I was just in Brazil and I wanted to stay at the Copacabana Palace, and since LVMH took over that chain, the Copacabana Palace had quadrupled its room rates.

Do you think there’s a limit to what consumers will tolerate with these price increases?

There doesn't seem to be. I saw a picture the other day of Jennifer Lopez walking around with a hundred-thousand-dollar Birkin bag. I'm like, “Who goes out of the house carrying something worth a hundred thousand dollars that somebody can take off your arm at any minute?” She probably has bodyguards with her, but that's crazy.

That customer doesn’t look at prices. Karl Lagerfeld was one of those. He made stuff for those customers, and then he had his Hedi Slimane or Tom Ford suits. I remember watching him shop at the Galignani bookstore in Paris. He must’ve bought a thousand books in fifteen minutes. “I want that one, I want two of those. I want that one for that house, and that one for that house.” There were people running around just taking all these huge coffee table books off the shelves, and some were a hundred, two hundred euros a pop, and then they had a truck come around and pick up the order. Those customers don't even think about what it costs.

What was the main thing you wanted to crack open about the luxury industry when you wrote Deluxe?

That it was a big business that had gone global and mass, and that it had sacrificed its integrity for the sake of profit. These were publicly-traded companies that were worrying about their shareholders, not their customers. I came at it from two different points of view. First, as a customer, because here I was, on my little Newsweek salary, able to afford to go to Prada and Gucci and buy a nice Tom Ford suit and look really spiffy and fabulous.

At the time — this was in the nineties — I'm like, OK, when I'm in Milan, I'm going to give myself a thousand dollars to spend. The first year I came out of Prada with a three-piece suit, with pants and a skirt and a jacket; three pairs of shoes; a handbag; and a sweater or two. The next year, I came out with a pair of shoes and three cardigans. Then the next year I came out with two sweaters. Then the next year, I got one.

Meanwhile, these groovy little cashmere cardigans I was buying, the first year they were knit really beautifully — no seams, the buttons were fantastic. By the third or fourth year, you could see that they were made differently — they had seams — and when I washed them, the dye would wash out in the sink. I put them next to the one I bought three years earlier, and they were clearly inferior quality but they also cost more money. From a consumer standpoint, I thought: Something is amiss here.

At the same time, I kept reporting that these companies were making record profits. That's when I thought, I’ve got to write this book to tell the consumers what I'm actually seeing as the reporter. At the time, Louis Vuitton even famously put out an ad where they had someone sewing a Louis Vuitton bag by candlelight, like a Vermeer painting, and they had to pull it in the UK because it was seen as untrue advertising. They were basically saying, “We make everything by hand,” when, in fact, it was being produced in a factory on an assembly line.

I wanted people to understand that what they were paying for was marketing, and that they weren't getting anything wildly special, because it was just mass-produced, overpriced stuff.

In the book you talk about the “cult of luxury,” which you describe as tycoons like Bernard Arnault “shift[ing] focus from what the product is to what it represents.” How has the cult of luxury changed since you wrote those words?

It’s shifting back, especially in things like high jewelry. You see them doing it at Tiffany in particular, where they've gone back to the Jean Schlumberger archives, and they're mining those designs. But when you buy one of those pieces, you're getting a very special piece of jewelry. What you're getting mid-range or entry-level at Tiffany is probably very average. Nice, but nothing special. But if you're buying at the high-jewelry level, you are definitely paying for what you get. Probably four times more than you should be, but it’s something special and nice.

In Deluxe, Arnault tells you in an interview, quoting Christian Dior, “What counts with critiques is not whether they're good or bad, it’s whether they're on the front page.” Do you think that's still true?

Yes. We just saw that with the Balenciaga [pre-fall] show. What were we looking at? Shoes for Goofy. It was just so ridiculous. But it just emblazoned the name all over the place, and people aren't going to remember how ridiculous it was. They're just going to remember there was this incredible, outrageous show in L.A.

And Cardi B was in it.

Absolutely. That's why they just had that enormous show in Hong Kong with Pharrell, where they lit up the sky [with “LV LVers.”]

Then why do these brands seem so sensitive about their coverage?

Because they're traded on the stock market. Kering still really hasn't recovered from that Kanye disaster. [In October 2022, Kering-owned Balenciaga severed ties with Kanye West after his anti-Semitic statements.] One false move, one thing said against them, anything that looks slightly bad, they have a panic attack, their shareholders are calling. I know somebody who specializes in crisis communications for luxury brands. It’s a “crisis” not just because of their reputation; it’s about their stock price. The reason that Bernard Arnault is the world's richest person today is because the stock market is doing so well.

When you do an interview with a designer today, there's four or five handlers in the room, and they’re interrupting and saying, “He didn't really say that,” or, “They didn't mean to say that,” or, “You can't use that.” They're so flipped out that something might get out that isn't on point or on message. Designers are like politicians now.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. To support the independent journalism you read here, become a subscriber.

Kering has had a rough go of it lately with Balenciaga, but also I wonder how the Gucci rebrand will do. WWD had a story about how a financial analyst downgraded Kering shares based on the Ancora show failing to produce a “big bang” in Milan.

It got panned critically, but that doesn’t matter. Nobody outside of fashion reads that stuff; it’s a lot of navel-gazing. I learned at the Washington Post 35 years ago that actually who you were writing for and who really matters is the shopper in the Nordstrom store in Tysons Corner [just outside Washington D.C.] who's pawing through the rack. That is the reader, that is the customer.

Here’s a quote from Miuccia Prada from Deluxe that presaged the stealth wealth trend of the 2020s: “Real luxurious people hate status. You don’t look rich because you have a rich dress. When you look at a person, do you see the spirit or the sexiness or the creativity? Just to see a big diamond, what does it mean? It’s all about satisfaction. I think it’s horrible, this judgment based on money. It’s all an illusion that you look better because you have a symbol of luxury. Really, it doesn’t bring you anything, it’s so banal.”

That's why Prada has been such a success, because it's based on snobbism. Because I said that in the book, I've been banned from Prada ever since. She was raised that way. She was a third-generation luxury peddler on her mother’s side, but also old money on her father’s side. She grew up in a household with servants, so that's what somebody who grew up in a household with servants would say. Literally around the corner was Donatella Versace, who was first-generation wealth with servants. Versace was all about showing off your wealth.

You’ve lived in Paris for a long time. What is the perception of the Arnaults over there?

The Parisians are getting really fed up. I was at a cocktail party last week and the conversation — and this is with fashion people, wealthy entrepreneurs, even a fashion PR person — all anyone could say was: Enough. “They own everything. It's just grotesque — enough.” “How can they shut down half the city for a fashion show? Enough.” “How can they be sponsoring the Olympics? And we're going to see that logo everywhere — enough.” “How can they own every single wine that's on the wine list? Enough.” “How can they take every single building and turn it into another store for the group or a hotel for the group? Enough.” “We don't want these people owning all of France, we’re fed up.”

[Bernard] is reaching saturation point. I think one of the reasons is because now his children are in power positions and commanding as much airtime as he does, so it’s like you have six times more Arnault out there. Everywhere you turn, they bought another place. I went to a new bar on the Boulevard Saint Germain. My husband said, “You know, who owns this bar? LVMH.” And in Saint Tropez, where Bernard Arnault has a summer house, and recently bought the biggest, most famous vineyard there, Minuty, and has the fanciest hotel, the Cheval Blanc, and has the hotel on the square, plus all the stores, a municipal councilor blasted the whole situation and called Saint Tropez “LVMH Ville.” So that kind of tells you how the French are thinking about them.

Finally, when people buy luxury today, what are they paying for?

Marketing. And Bernard Arnault’s fabulous lifestyle.

Get Deluxe and read more from Dana Thomas on Substack.

Earlier in Back Row:

Subscribe to Back Row

The fashion and culture newsletter that publishes what legacy media can't.

I read Deluxe when it came out because I was very interested in fashion, but I feel like what it taught me the most about was capitalism, and the dynamic range of wealth inequality. The example that prior to Prada becoming a corporation, the Prada family had two houses – – a home in Milan, and a summer home -- has really stuck with me. They were undeniably wealthy, they made a good product, their employees were paid well; and that wasn’t enough for capitalism.

The luxury space is truly a whole different world from any other kind of retail. It makes me sad that brands have moved away from aspirational customers in favour of the uber-wealthy who hardly need another bauble for the collection. I'm also extremely sad that LVMH has taken over the world. In particular, the classic charm that Tiffany held for so long is just gone into the marketing void that is LVMH. It's all part of the same machine, which is the antithesis of what luxury brands used to be: unique, highly crafted, special pieces that became heirloom treasures. Tis to weep.