Pharrell's at Louis Vuitton, But Where's the Hip-Hop Met Gala?

Fashion's road to embracing hip-hop has been a bumpy one, as the new book Fashion Killa by Sowmya Krishnamurthy explains.

I will be hosting an Instagram Live with Fashion Killa author Sowmya Krishnamurthy on Thursday, October 12, at 3 ET. Please join us! We’ll be taking audience questions.

“Oftentimes, hip-hop stories don't really get told in the publishing world,” said Sowmya Krishnamurthy, author of the new book Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion in a recent interview. She notes in the book that by 2017, hip-hop had become “the most successful music genre in America, surpassing both pop and rock, in terms of overall consumption. Six of the top ten artists that year were rappers, with Drake and Kendrick Lamar taking the top two spots, respectively. Hip-hop had outlasted the critics that said it was just a fad, ephemera, noise.” The genre’s superstars became some of the world’s biggest fashion influencers, setting trends, putting brands on the map, and disrupting the system by launching their own clothing lines. “Like preachers, they propogated luxury to the hungry and poorly dressed masses. Their music was the primer to learn about exotic brands: Versace, Balenciaga, and Balmain,” Krishnamurthy writes.

Krishnamurthy started her career in music. She moved to New York from Kalamazoo, Michigan to intern at Bad Boy records, then did the agent training program at William Morris Endeavor. “You start in the mail room. I thought that was maybe a metaphor, I didn't realize you pushed a mail cart, and that's what I did. You push a mail cart, you're delivering mail to agents, usually doing a very bad job and getting yelled at on a daily basis. That was my first foray into the business,” she recalled. After holding jobs in marketing and PR, she switched to music journalism, which she’s been doing for the last decade. Ahead, our conversation about her book, which is out today.

When I was reading your book I kept thinking that this is basically a blueprint for the Met’s Costume Institute to do a fashion and hip-hop show or a streetwear show, which would mean a hip-hop-themed Met Gala. Don’t you think it’s time?

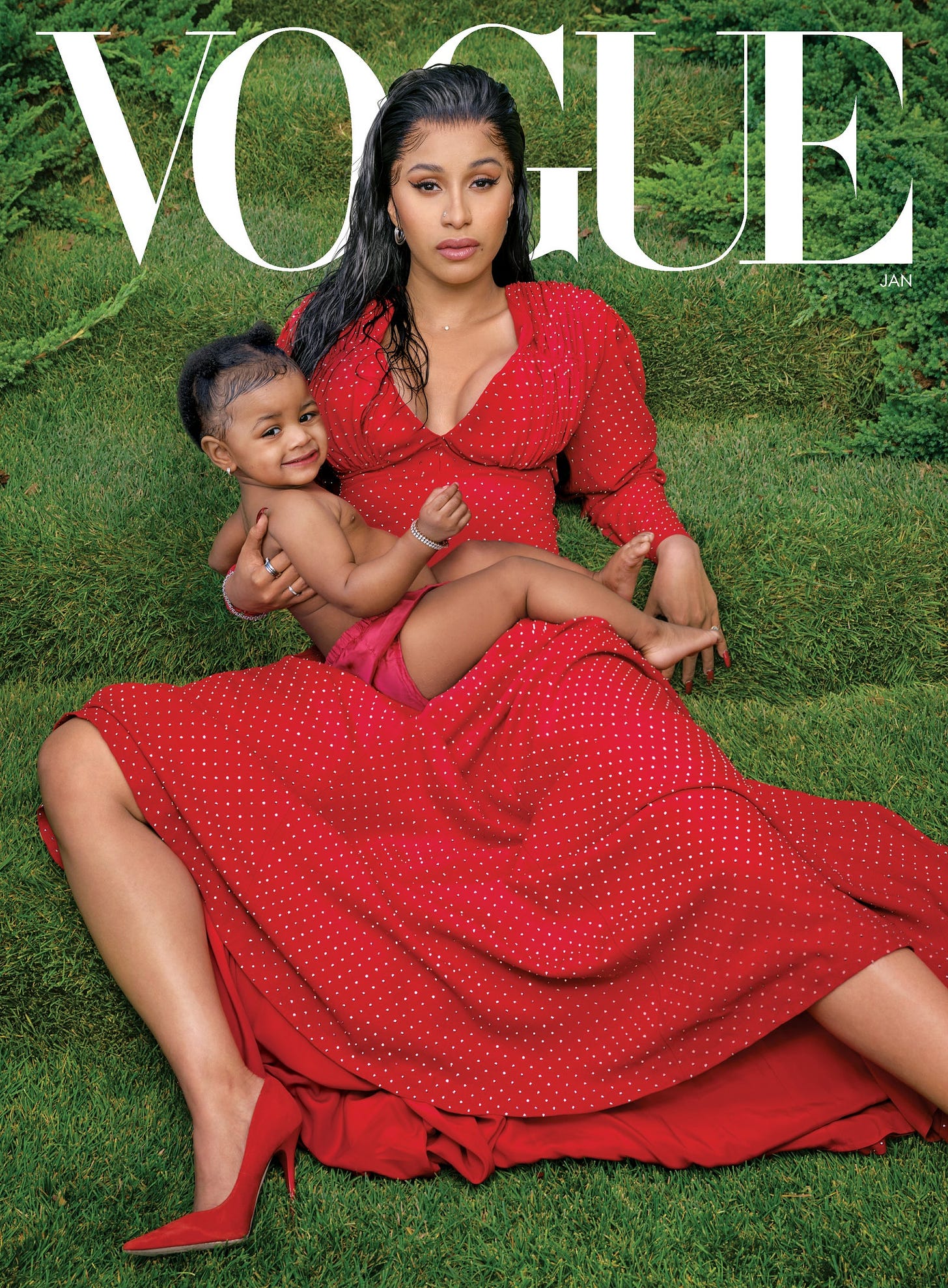

I think it's time. And in fact, this would've been the best year, for hip-hop's fiftieth anniversary. But I think when it comes to the idea of hip-hop fashion, oftentimes these very respected places like Vogue – I don't know if they know what to do with that. Cardi B was the first female rapper on the cover of American Vogue. It wasn't that long ago.

What I would love is for that to be an opportunity to celebrate hip-hop designers who haven't gotten their flowers – Karl Kani and Cross Colours and April Walker and Kimora Lee Simmons.

Met Gala themes and Costume Institute exhibitions have to check a few boxes. One is sponsorship – are there brands that will underwrite it? Another is the appeal to the audience – will people want to come and see the exhibition? And the third is the guest list – will celebs come walk the carpet? And hip-hop fashion seems to check all those boxes. So it just perplexes me that they haven’t done it.

I would hope all of these brands — Chanel, Balenciaga, Balmain — who've taken and continue to take from hip-hop inspiration, that they would help underwrite. That it isn't, Well, it isn't our brand, so we don't want to be involved.

If anyone wants me to curate it, hit that email.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. The best way to support the independent journalism you read here is by becoming a paid subscriber.

What are the top two or three ways that hip-hop revolutionized high fashion?

One of the biggest has been through entrepreneurialism. With hip-hop, there's always been this idea of hustler culture. You started to see rapper-led clothing lines, whether it be Puffy’s Sean John or Jay-Z's Rocka Wear, even Kimora Lee Simmons’s Baby Phat. It's this ethos of, I know what I'm doing is cool and I should be making money off it. I should have my name across my back, not somebody else's. We now see some iteration of that with Pharrell at Louis Vuitton.

Another way is this evolution from being outsiders. This book starts in 1973. Hip-hop was considered this underground genre, it was written off as a fad. It was what kids were doing in New York at the park, at the block parties, messing around in their parents' rec rooms. And then on the fashion side, they just weren't able to afford the clothes. And even when they were — are you reflected in the advertising? Do you feel welcome when you go downtown to a high-end boutique? Or are they kind of looking at you and questioning where you're getting your money from?

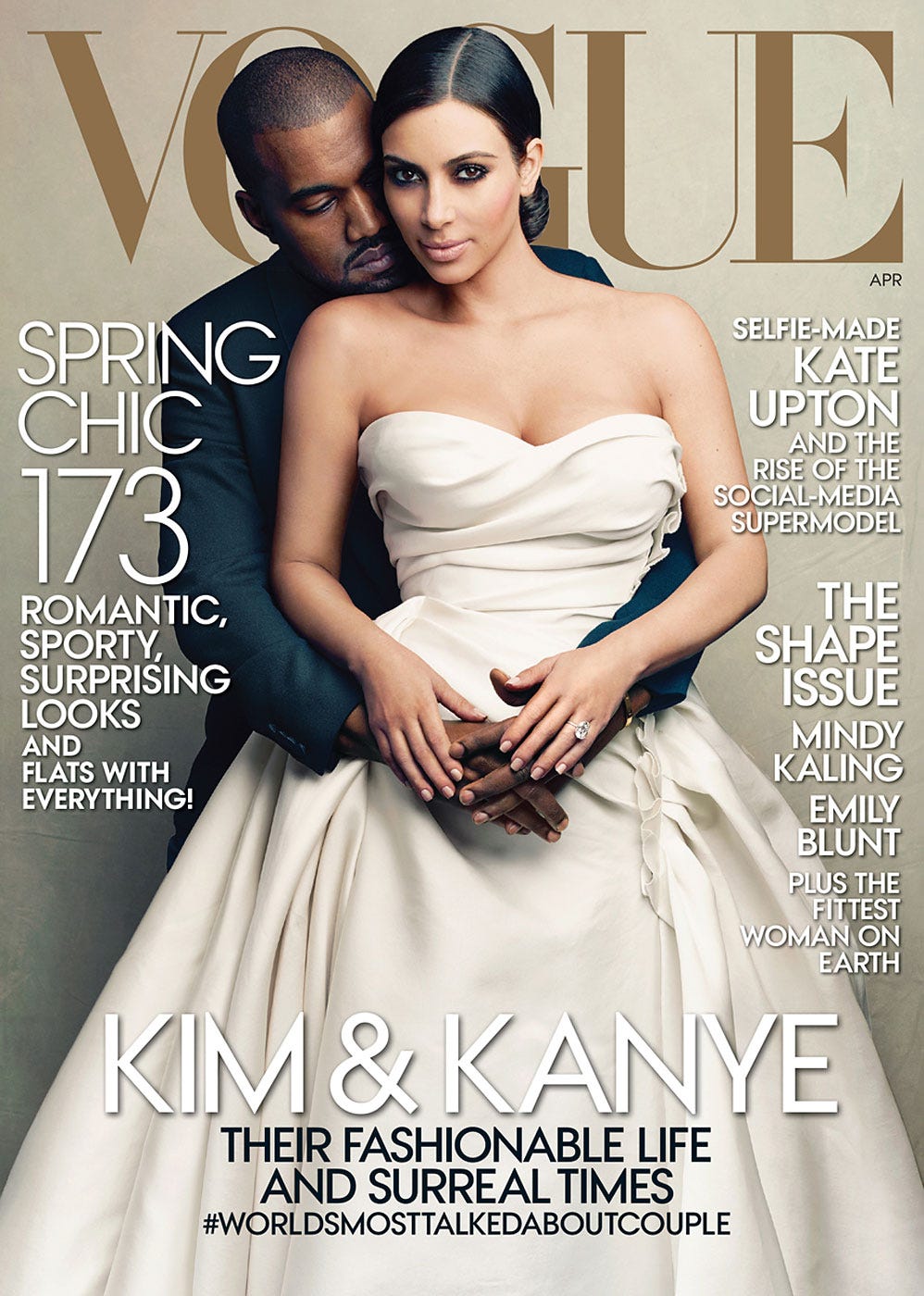

Throughout the book are scenes of the fashion industry taking notice. Run-DMC in that famous moment at Madison Square Garden, where everyone's holding up their Adidas, that led to their million-dollar deal with Adidas. Puffy launching Sean John to compete with people like Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger and winning the CFDA award. Somebody like Kanye getting on the cover of Vogue magazine. When I spoke to people behind the scenes, they said he went to Anna Wintour and pled his case to be on the cover. And his then wife, Kim Kardashian was with him as kind of this iconic New American couple.

Pharrell at Louis Vuitton has been fascinating to watch. How do you view that partnership?

When Louis Vuitton had to replace Virgil Abloh, I think they were put in a very tricky position. Virgil was very respected by hip-hop and high fashion. Who would do his name justice, but ideally also take it to the next level? And someone like Pharrell, I think, makes a lot of sense. He has a well-established passion for fashion. He helped usher in streetwear with his lines BAPE and BBC. Early on, he made it clear that he wanted to be taken seriously within luxury fashion, forging relationships with Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Jacobs. I almost feel like he had this long game planned.

When you think about his Paris fashion show – who else could bring together Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Rihanna to model the line when she's pregnant? I can't think of one other person on this planet who could do that for the brand. Who knows if Louis Vuitton is thinking 10, 20 years down the line? Probably not. But I think in the short term, this was a nice passing of the torch.

The celebrity assemblage was wild. We didn’t see anything come close to that during this recent fashion month.

It’s funny, at New York Fashion Week, I was talking to a few people behind the scenes, and I said, “It's been kind of quiet for hip-hop.” And they said, “Everyone came out for Pharrell in Paris.”

Do you think that becomes a template for other luxury brands? I think a lot of fashion people worried that celebrity appointments would become the norm but so far that’s not bearing out.

It's tough for brands if they start playing this game of who has the biggest celebrities. I would hope brands don't fall into that. If fashion week does sort of go back to its roots, I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing. There will always be the big celebrity spectacle, but for other brands, your job is to sell clothes and your job is to show what the next season looks like. I think you should be able to do that without a bunch of celebs there. If your line is dependent on that, I don't know if that's a very sound business model.

Which labels embraced hip-hop earlier in its history and how did they benefit from doing so?

I have a whole chapter devoted to the year 1991, which was a milestone year because high-fashion brands were starting to pull from hip-hop influences. There's that famous Chanel show by Karl Lagerfeld where models are wearing gold jewelry and stacking chains on top of each other. That same year, brands like Isaac Mizrahi and Charlotte Neuville [showed hip-hop inspiration] on the runway. [Ed. note: Mizrahi’s show opened to Sandra Bernhard rapping, “Homegirl look is the only way.”] Many in the media saw the connection to hip-hop, but that line between appreciation and appropriation was still very fuzzy. And I don't think anyone from the hip-hop world got a check or name recognition, it was just, This is going on in the streets, this is what the kids are doing, and we're going to make it cool and make it really expensive.

Later as we're getting into the nineties, brands that now are still a staple of hip-hop, like Timberland, like Carhartt, these American work wear brands, didn't really like that hip-hop was embracing them. The media created the archetype of the drug dealer – baggy jeans, Timbs, a baggy coat. That's not to say that someone might not have dressed that way, but it was almost a way to scare these brands – that if any Black or brown person is wearing your clothes, then they must somehow be a criminal.

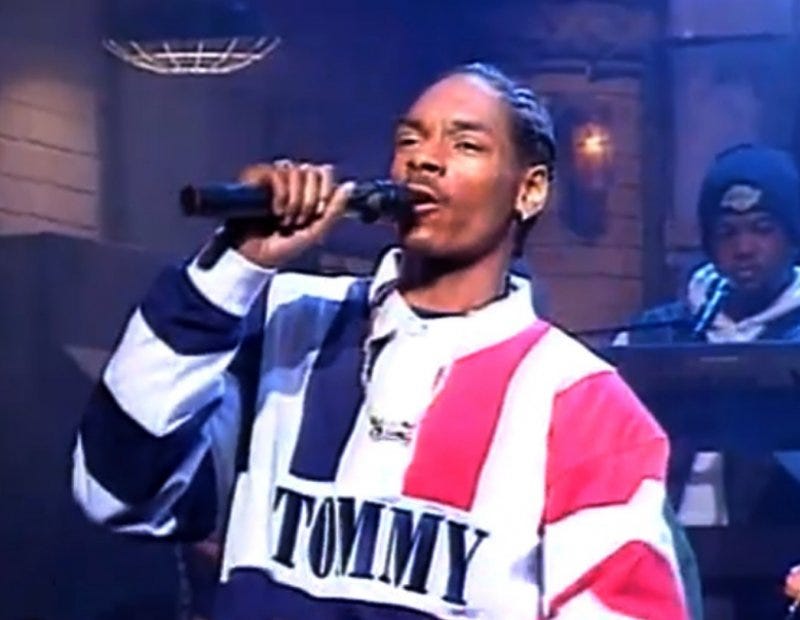

A brand that I think did it really well and has benefited greatly was Tommy Hilfiger. He was the one who put that famous rugby on Snoop Dogg. Snoop ended up wearing it on Saturday Night Live, and it was a game changer for the brand. A young Kanye sitting at home in Chicago saw that and remembers that moment of like, Wow, who is Tommy? I need to wear his clothes.

The hip-hop show Karl Lagerfeld did for Chanel was controversial at the time, right?

Some within the fashion industry, like buyers, were like, I don't think a Chanel consumer wants a bedazzled catsuit or this baseball cap or this quilted bag in gold. Who is the demographic for this? So there was definitely some backlash there. Also, notable Black media figures said, look, when Karl Lagerfeld does it, it's cool. But when a young person dresses like that in real life, they're looked at through a negative lens. Those conversations were happening even in 1991.

The fashion industry has come a long way in terms of embracing diverse talent. From your perspective, how much work is left to be done?

When it comes to access, it’s probably gotten better. A lot of artists can afford to buy off the rack. Not too long ago, Cardi B would be posting videos as a stripper on Twitter, and then she becomes a reality star turned hip-hop princess, and now she's being dressed by Schiaparelli for Paris Couture Week. I've never seen such a meteoric rise in fashion and hip-hop. Brands see how many views those videos are getting, how many followers these artists have. Even if there's not altruistic reasons behind it, it's just good business to work with them.

Back Row is a reader-funded publication. The best way to support the independent journalism you read here is by becoming a paid subscriber.

Stealth wealth has been a big trend lately. But can you explain the significance of logos in hip-hop and the influence of Dapper Dan?

Dapper Dan was the father of logo mania, which is his term. He took the logos of these heritage houses like Louis Vuitton and MCM and Gucci, and created his version of what he calls knock-up [versus knock-off]. So imagine that Chanel logo on a bomber jacket, or an outfit made head-to-toe with the Gucci logo. Gucci doesn't make that, but someone who likes Gucci and wants that look would go to Dapper Dan. Logos signal to the world that you can afford expensive clothing.

One thing I wanted to do with the book is explain the psychology of luxury. Why do people want to wear these clothes? We have to go back into history and look at dress codes and sumptuary laws. At one time there were literal rules of who could wear what based upon your stature in life – are you royalty? Are you not royalty? In America, oftentimes fashion or fabrics were able to signify if a person was enslaved or free. I dive into this in my chapter about the Lo Lifes who famously used to steal Ralph Lauren and wear it head-to-toe. If you are wearing those logos very prominently in certain neighborhoods, and you're safely able to walk around, that means that you are powerful and strong and nobody's going to fuck with you.

What are you waiting for? Get Fashion Killa here or swing by your local indie and buy it there.

Dapper f@$king Dan 💕💕💕💕💕

Great call on the Met show.

Such a strong interview

The title is equally fab

Loved this interview, super interesting and insightful! Fashion today owes loads to hip hop music and artist on every level, so definitely that Met Gala should be on the works. Can't wait to read the book.