Oscars Reveal Cracks in Hollywood-Fashion Industrial Complex

Where can the marriage of Hollywood and fashion go from here? To the Met Gala, for one.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row! If you haven’t yet, don’t forget to preorder my book ANNA: The Biography, out May 3. (If you are in the U.K. or Australia, it’s out May 5; other international publishing dates are to come.) This newsletter is free to read, and you can support it and me as a writer by picking up the book. If you are new here, subscribe to get more posts like this sent straight to your inbox around twice a week.

Kristen Stewart wore plain-looking black shorts and heels to the Oscars and then changed into flats and socks after posing for photos. It was like she had commuted to work, walked to her cubicle, and was settling in to take Zoom calls. And that seemed like a perfectly appropriate attitude for the whole thing.

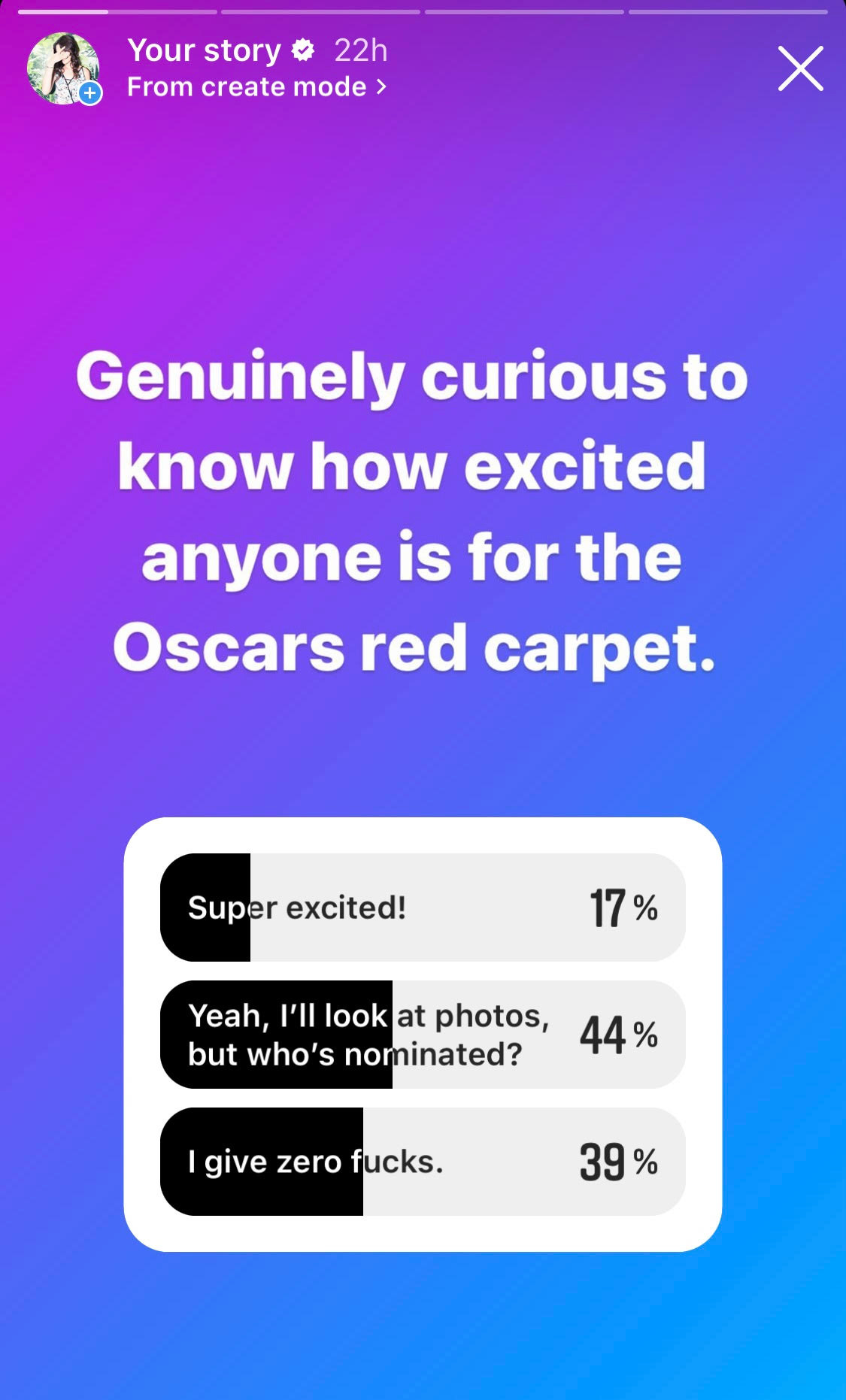

Oscars fashion and analysis of it used to be a highlight of the year, something people who enjoy fashion and entertainment went out of their way to watch over the course of two or three nights. But it’s become just another red carpet event. For many of us, it’s surely north of a perfume launch, but also definitely less exciting than the Met Gala. This must be thrilling to Anna Wintour, Queen of Fashion, who will probably rule over her red carpet on May 2 with a shell dangling from her neck containing not the most beautiful voice of the sea*, but the whole “everyone cares” vibe the Oscars once possessed. Calling the Met Gala “the Oscars of the East Coast,” as many have long done, no longer makes sense, but calling the Oscars “the Met Gala of the West Coast” also feels wrong. Just look at my super scientific Instagram Stories poll:

The fashion relevance of the Oscars has diminished for a variety of reasons, including the decline of movies, the rise of social media, and shifts in the broader socio-political consciousness as it pertains to cultural events like award shows. There’s also the fall of the ceremony itself, which was watched on Sunday night by an average of 15.4 million viewers, making it the second-lowest watched ceremony ever, Vulture points out. But the fall of this red carpet in particular hints at significant cracks in the fashion-entertainment industrial complex as we have long known it. Kristen Stewart was probably contractually obligated to show up in Chanel, but it’s possible that labels will soon start placing little or no emphasis on Oscars appearances when they sign celebrity faces, instead budgeting for things like the Met Gala or even TikTok posts.

When I was growing up in Austin, Texas, I loved watching the Oscars — the pre-show, the ceremony, the post-show, and Joan Rivers talking about it all the next night. Most of the programming was boring, but it was also urgent. I have distinct memories of watching Nicole Kidman walk onto the carpet in chartreuse Dior by John Galliano (1997), Sharon Stone in a white Gap shirt (1998), Gwyneth Paltrow in pink Ralph Lauren (1999), and Bjork in swan (2001). If I wanted to witness fashion and celebrities coming together, my options were to look at magazines or watch these things on TV. Most of the magazines I liked came once a month, so when I got my hands on one or got to watch an awards show, it was special.

The marriage of celebrities and fashion has long been normalized, but it wasn’t always a given. In the late eighties and early nineties, supermodels — not actresses — were the faces of fashion, and they reliably appeared on monthly fashion and women’s magazines, in music videos, and as hosts of MTV’s House of Style. They were replaced by actresses on magazine covers in the late nineties, Anna Wintour and Vogue being at the forefront of this sea change. Anna correctly sensed that the public’s interest was shifting from models to celebrities, and through events like the Met Gala, which she’s planned since 1995, she pushed fashion and Hollywood closer to one another. Celebrities proved a useful conduit for bringing high fashion brands to the masses, and naturally became the contracted faces of these brands. This heightened the significance of the Oscars, which was ground zero for the nexus of celebrity and fashion.

Around the turn of the century, internet media became more significant, and monthly fashion magazines and awards shows started to become less special and less escapist. Runway slideshows became a staple of the fashion internet. Facebook launched soon thereafter, in 2004, and introduced newsfeed in 2006, forever impacting media consumption patterns. Blogs like Go Fug Yourself — still one of the best places to read about celebrity fashion — started to take off. Instagram came along in 2010, placing increased emphasis on images as a tool for online storytelling. Fashion found at least that platform appealing, and glommed on.

But when the celebrity cover shift happened in the late nineties, it benefitted a specific type of celebrity the most: movie stars. Television actresses and pop stars appeared less often than the faces of film because, in Vogue’s eyes, movies reigned supreme. This made some sense, given that movies were events in a way they are not today — something people looked forward to for months and bought tickets to see in theaters.

Of course, this approach also had serious pitfalls. The film industry — like fashion — was not diverse or inclusive, and chasing the top movie actresses might have been a lucrative formula during print media’s last years of relevancy, but it reinforced a lens of whiteness. As that lens became rightfully critiqued instead of blithely accepted, award shows and magazines became tiresome institutionalized cultural problems instead of special and fun.

April Reign started #OscarsSoWhite on Twitter in 2015 after she watched the announcement of that year’s nominees on television. It began trending shortly after she posted the tweet, but has set the tone for both awards shows and the entertainment industry generally ever since. That was the same year that Fashion Police co-host and E! red carpet staple Giuliana Rancic made offensive comments about Zendaya’s hair on the Oscars red carpet. Rancic apologized on air, but the show never recovered, and was canceled in 2017. (The show’s original host Joan Rivers had died in 2014.)

Then in October 2017 came the downfall of producer Harvey Weinstein, whom Jodi Kantor and Meghan Twohey of the New York Times revealed had a long history of paying off his sexual assault victims. This reinvigorated the Me Too movement, started in 2006 by Tarana Burke, but also cast a pall over the Oscars, for which Weinstein was known to campaign aggressively. In 2018, actresses wore black dresses on the Golden Globes red carpet to protest sexual misconduct in Hollywood. Before the event, The Cut published a post headlined, “Why We Won’t Be Ranking Golden Globes Fashion,” which read, “Ultimately, we’re doing this out of respect for the cause and in acknowledgement that, well, the game has changed. At least for one night.” This year, the Golden Globes occurred with no red carpet and no telecast following a series of damning revelations, including that none of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association’s more than 80 voting members were Black.

With the Oscars coming back to its usual form this year after a weird pandemic iteration in 2021, and with no Golden Globes to serve as a warm-up act, this could have been a truly big fashion event. But while there were some great fashion moments, the Oscars feel — as the Met Gala once did — like an industry event.

But the interesting thing about all this is that an appetite for fashion and fashion coverage has probably never been greater, because the fashion-inclined among us are accustomed to consuming this content all day, every day online. E! may have botched its red carpet coverage, but it’s no matter, because instead of Fashion Police, we can watch TikTok videos of people critiquing red carpet looks. And we know that if we follow fashion and celebrity even casually, we will see images and videos of the Oscars red carpet on social media whether we seek them out or not. What was once appointment viewing can now be, for many people, casual, everyday scrolling.

Part of the lack of urgency around the Oscars red carpet may be that fashion itself has been shifting away from actresses. Just look at Vogue’s covers since 2020 — actresses are in the minority of subjects, with models and pop stars appearing more frequently. Yet actresses like Zendaya, the face of Valentino, who have huge social media followings and approach fashion in a fun, über-glamorous, delightful, and surprising way are outshining their peers because of it.

The Met Gala promotes an over-the-top approach to fashion that actresses once avoided for fear of being typecast. But on the internet, over-the-top gives people who look at fashion all day something new and delicious to DM their friends about. Anna Wintour, who still leads Vogue and the Met Gala, and who has had both the fashion and entertainment industries under her thumb for decades, helped create a world where the Oscars red carpet mattered. And by promoting the status quo and the idea that it wasn’t problematic for so long, she also likely inadvertently contributed to its undoing.

In the end, she and Vogue and the Met Gala benefit from the decline of awards shows. But this should also remind us that, for all the progress that’s been made in recent years, power in this world is still concentrated in the hands of a few people. And she is still one of them.

*Yes, this is a reference to The Little Mermaid. My husband says he’s “not sure how many people will get it.” Another friend says it’s “deep cut.” I don’t want anyone to miss out on the joy of remembering The Little Mermaid.

If you haven’t yet, don’t forget to subscribe to support independent, ad-free fashion journalism.

I think another reason why the Oscars Red Carpet feels so anticlimactic is because nowadays, every movie premiere, festival appearance, etc. is treated like another Oscars Red Carpet. When we were growing up in the 1990s, it was basically just the Globes and the Oscars. Everything else was an industry event, with decidedly unglamorous red carpets that weren't posted everywhere on the Internet. Now everything -- from a premiere to a South x Southwest panel -- requires a borrowed (often custom made) designer outfit. It makes the Oscars less special.

Wintour's genius with the Met Gala is that she's turned it into a costume party. In a way, the Oscars have become a costume party too (celebs don't wear their own clothes anymore, etc.), but at the Oscars the costume is a heightened version of themselves or the character they play, a kind of brand extension. The Met Gala encourages them to go beyond that, to wear really fantastical (if tacky or ridiculous) get-ups, to pay homage to FASHION as opposed to themselves.

Great article, particularly the Little Mermaid reference.