Media Industry to Repeat History

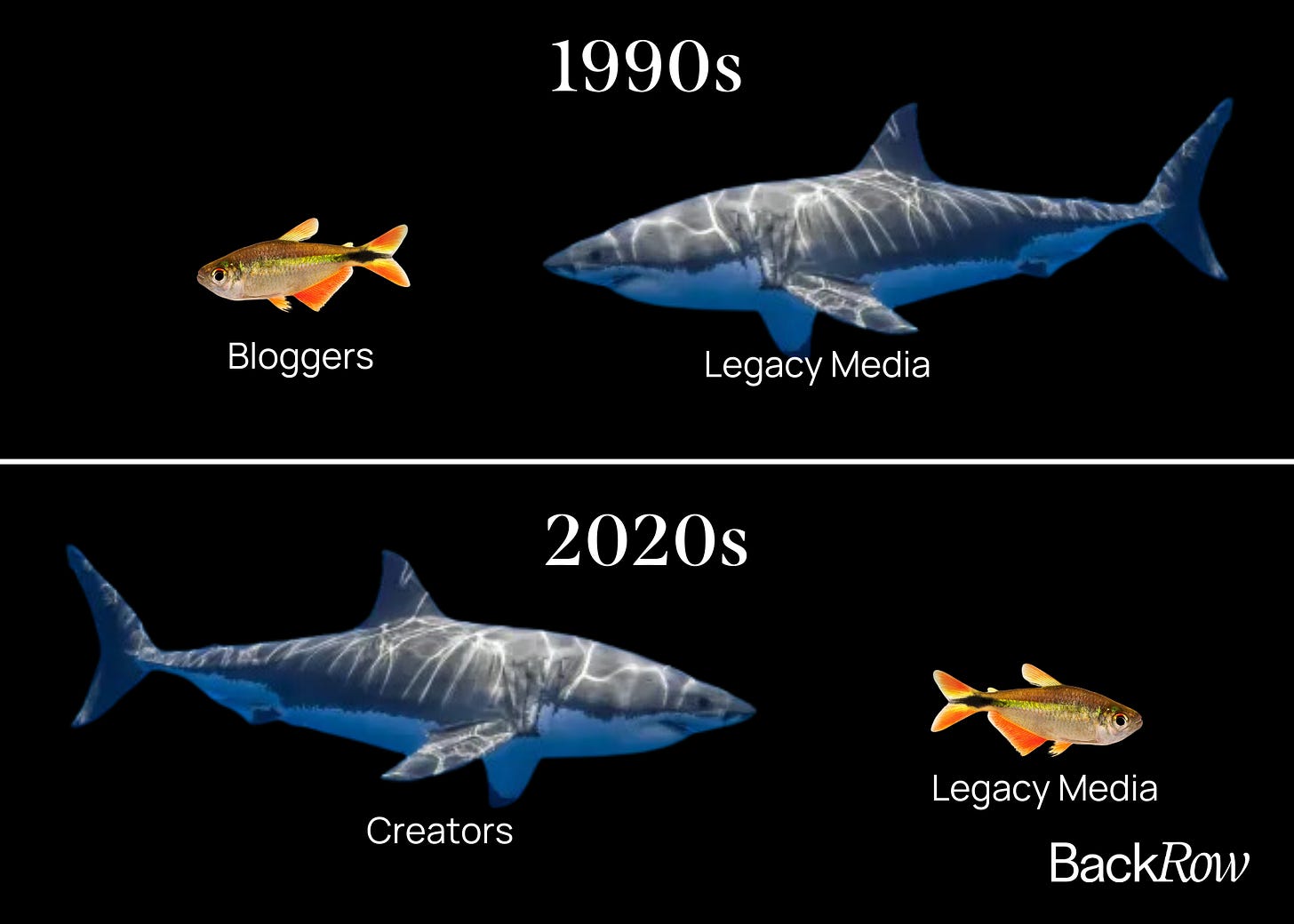

Media execs miscalculated when the internet came. They're doing it again with the creator economy.

One of the best responses to New York magazine’s cover story about the opinions of “media elites” on the state of media today came from A Media Operator, a business of media newsletter. Jacob Cohen Donnelly writes:

There’s a big section head in the story that says: “The media’s most promising new business idea? Make something worth paying for.” I’m sorry, what? That is an insane thing to read in 2024. We’re really surprised that we should make something worth paying for?

That, my friends, is the crux of the problem for our entire industry.

He goes on to argue that, as The Ankler CEO and founder Janice Min said in the story, the media lost sight of delivering value to its audience since executives were focused on generating returns for investors, thinking they could make Big Tech money. The result was a rush to the bottom, where websites tried (and failed) to compete with Google and Meta for ad business by scaling as cheaply as possible.

The executives who did figure out how to scale made it to the top of the industry, Cohen Donnelly notes. He writes:

Here’s the problem… the people who made it to the top are still in charge of many of these large media companies. And they are often the worst positioned to make these companies work going forward. No one who has had to deliver value to an audience would ever stop and go, “Huh, I guess I should create a product that people want to pay for.” But in our industry, those people make it to the top.

Some of these executives feign befuddlement about newsletters that charge readers, which would concern me if I had a staff job working for one of them. The reality is that newsletters like this one will be able to expand and increase audience while Ye Olde legacy businesses only seem to contract, lay people off, and lose readers.

Here’s one anonymous “longtime media executive” who spoke to New York’s excellent Charlotte Klein for the package:

“I’m surprised that people are okay with the subscription model, where they don’t have that many listeners or viewers but are making money, so they’re just good with it,” says one of them. “The Substack writers, people with Patreon podcasts. My generation was wired completely differently. We wanted to be read or listened to by as many people as possible. And now this new generation is like, I’m totally cool with having 9,000 die-hard fans.”

You have to laugh because it’s the only way to process the type of person who would say this. These newsletters are quite often the difference between journalists being able to continue their careers or not, since these executives certainly aren’t paying them enough to do it. Newsletters also allow writers to have a direct relationship to their audiences and ownership of the email list for those audiences. This is a huge part of the appeal. When a journalist builds audience for a media company and that media company lays that journalist off, they don’t get to take the audience with them.

What’s concerning for the talented people who still have staff jobs is that these executives are not feeling appropriately threatened by the creator economy that has for a while sustained influencers, and now sustains writers.

When reporting ANNA: The Biography, I heard a lot about the mistakes Condé made circa 2000 when the internet was taking off and they realized that their magazines should, like, have websites. Executives worked there who suggested things like charging for articles and shlocking product — and they were ignored and/or fired because other executives were content to continue relying on print ad money. What did all that hubris lead to? Well, we can look at 2024 Vogue, which put Kamala Harris on its “digital cover” this month only for the reaction to be one big shrug. (Anna Wintour and Condé CEO Roger Lynch declined to speak to Klein.)

I’m unavoidably biased on this topic as someone who now, blessedly, makes a living from Substack. If these media executives had been paying attention to the fashion beat, they could have seen how the trajectory of fashion influencers provides a template for the broader media industry today. At first, the old-school critics and editors who were getting worse seats at fashion shows because brands wanted to host popular bloggers, like Tavi Gevinson (Style Rookie) and Susanna Lau (Susie Bubble) and Bryan Yambao (Bryan Boy), griped about it. They maligned what they argued was a lack of expertise and training. But while they could resent it, they couldn’t fight the creator economy that was about to hit them like a tsunami. And guess what happened to those creators? They translated their blog readership into massive social media followings. And they became editors! Gevinson went on to found her own youth website, Rookie, which was more culturally influential than, say, Seventeen, even if it folded. Lau now contributes to magazines like System and writes runway reviews for Business of Fashion. And Yambao is the editor-in-chief of the magazine Perfect.

Meanwhile, Tina Brown, who edited Vanity Fair and The New Yorker during the height of magazines, is now on Substack herself. When Anna leaves and Vogue has to appoint a new editor, what type of person do you think they’ll hire? Someone with a private Instagram account and no name recognition? They’ll have to pick someone who could qualify as an influencer if they want to remain relevant.

The fashion segment of media was one of the first to deal with this sort of disruption, but newsletters are now forcing other beats — politics, tech, art, real estate, you name it — to contend with it as well.

The creator economy is in its early days, really. The mass adoption of television occurred in the 1950s, and the creator economy started in earnest around 2010, so we’re just about 15 years into it. It’s concerning that these media executives think they are superior to it and have a better way of operating, when they obviously do not. They should be trying to learn from it and fund star writers and podcasters of their own. At the least, they should try to figure out how to fund journalism itself! Which will vanish if enough young people decide they can’t make a living doing it, which seems to be the path we’re headed down.

While there was a lot of cluelessness in the story, there was wisdom as well, particularly from the fashion folks. I loved what Business of Fashion founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed said about covers: “The state of the fashion-magazine cover is somewhat diluted by the fact that anything can be a cover. So anyone could put a big logo on an image and call it a cover. And brands — even really, really prestigious media brands — are doing digital covers, whatever that means, right?”

Loose Threads

T Magazine has a big, delicious profile of Jonathan Anderson, who wants to be (already is?) the world’s best fashion designer. It reads: “That some of his fellow designers had gotten similar praise for work that Anderson sees as inferior to his — ‘You can’t just fake a formula’; ‘It’s the same product’; ‘It looked like Neiman Marcus’— infuriates him, as if the approval is meaningless when it’s not only his to receive.”

Former Abercrombie CEO Michael S. Jeffries, 80, and his partner Matthew Smith, 61, were arrested in Florida this week. Jeffries was indicted on charges that he ran an international sex-trafficking scheme while CEO. Accusations from the 15 people in the indictment include that they had been coerced into sex acts.

Kering announced third-quarter results and they were… not good. The group’s revenue decreased by 16 percent, worse than the expected 11 percent. Per Reuters: “Sales at Gucci, which accounts for half of annual group sales and two-thirds of profit, continued to slide and were down 25% in the quarter, compared to analysts' consensus expectations for a 21% decline.”

Meanwhile, Hermès sales are up 11.3 percent in the third quarter. The luxury sector is suffering largely due to declines in China, but while Hermès has seen lower traffic, shoppers are buying more stuff, like leather goods, jewelry, and ready-to-wear.

Beyoncé has a new fragrance called Cé Lumière. Like her previous fragrance Cé Noir, this one costs $160.

What Paid Back Row Subscribers Are Reading

This is not just a print media phenomenon. TV has been dealing with subscriber streaming services for years. Both Substack newsletters and streaming TV operate on the same principle: provide vertical curated content (focused on singular topics or interests) to people willing to pay for it without having to suffer through advertising. (I say this as someone who has spent 43 years in advertising and public relations). Choice and customization reign!

This is such a timely post given the Washington Post drama that hit us all this afternoon. Having control over your own content and the ability to publish what you want just became even more valuable (if that’s even possible). I can say that I have made more purchases from Becky and Leandra’s substacks in 2024 than I have from any other media source, including print and Instagram content. What’s funny about substacks is that it flys in the face that long form print is dying-it’s not-give us the opinions of people we trust and not only will we read it, we will pay to do so.