How the Obsession Over Tarte's Dubai Trip Spiraled into Conspiracy Theories

People seem uncomfortably eager to take influencers down.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. This newsletter is ad-free and funded entirely by readers. This is a new business model for fashion media, and one that enables Back Row to publish stories you won’t read anywhere else. If you want to support this work, the best way to do so is by becoming a paid subscriber for $5 a month — the price of a single coffee in a city — or $50 annually, which saves you $10 a year. Paid subscribers get around two Back Row posts per week, plus access to commenting.

If you are not able to pay right now, you can support this newsletter by telling your friends about it and sharing it on social media with a link.

Makeup brand Tarte recently sent 29 influencers and their plus-ones on a fancy trip to Dubai that frothed up an unusual amount scrutiny and truly bizarre conspiracy theories online. Influencers aren’t new. Influencer trips aren’t new. So how do you explain the internet’s, particularly TikTok’s, obsession with the trip? Perhaps the same way you explain the feverish anticipation of Insider’s Something Navy takedown story late last year. At the root of both may simply be that a lot of people really do not like influencers, particularly successful young women influencers. After building them and the job of influencing itself up over the past 15 years with our attention and double taps, much of the public just can’t wait to take them down or catch them doing something bad or wrong or somehow nefarious.

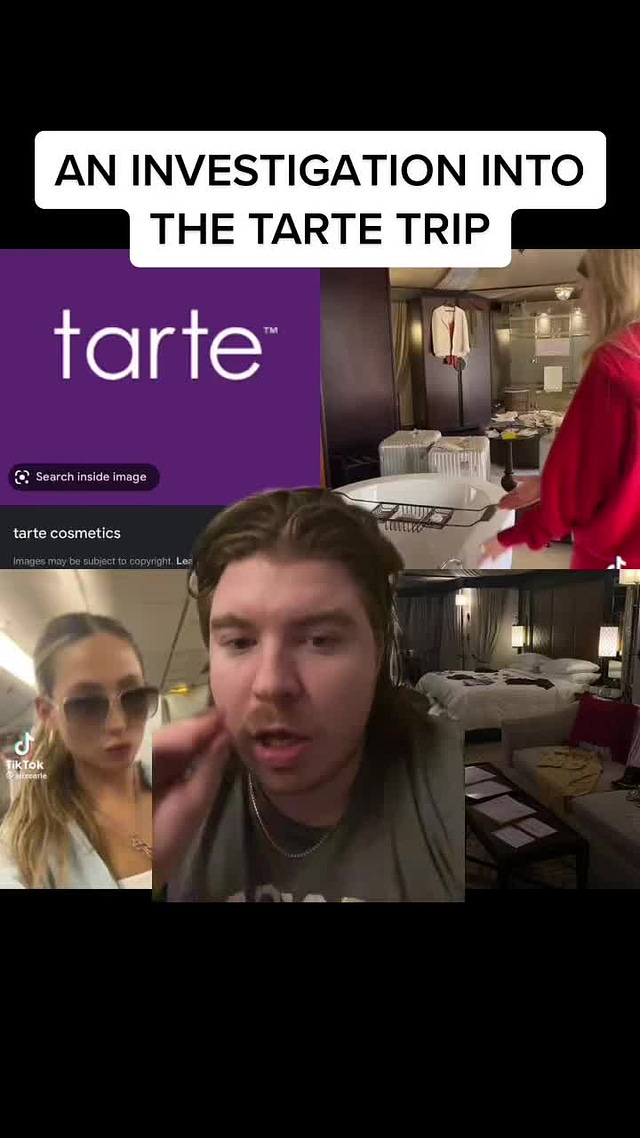

One of the early posts questioning the Tarte trip came from Bartstool Sports blogger and content creator Jack McGuire. In McGuire’s first Tarte video, which now has 6.6 million views, he says, “There’s something going on with this Tarte trip, and I’m gonna get to the bottom of it.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

He goes onto explain that “the economics of this trip do not make sense,” adding, “These ladies — and there was a lot of them — all flew first class on Emirates to DUBAI… Do you understand how much money that costs?” He shows a screenshot of a flight booking where the price of each ticket is $22,000. He notes that the influencers stayed at villas at a Ritz Carlton, and, “This is one of those hotels you can’t even find how much money it costs to stay there. You have to, like, call somebody because it’s like they know rich people ain’t fucking booking it on Expedia.” He says it must be around $5,000 per night, so call it $15,000 for three nights, plus the flight, plus whatever the influencers were paid, and he concludes that’s more than $65,000 a person. “These aren’t nobodies. This is Alix Earle. Alix Earle is probably getting a [Kansas City Chiefs quarterback] Patrick Mahomes contract for just going. Where are they getting this money from?” He Googled Tarte and proclaims, “Tarte was just this company that this woman came up with in her apartment in New York City that was built on credit cards and a dream. Guess what? Credit cards and a dream don’t get you to Dubai first class on Emirates, I’ll tell you that much.” He ends his video by saying he’s just done some “heroic journalisming” and “there’s something going on here and I won’t stay quiet.”

This fueled a wild amount of speculating about the trip. However, the basic argument here, that there’s no way this could be going on without an explanation, is wildly illogical. A beauty brand taking a bunch of influencers on a nice trip is as surprising as a commercial airing during the Super Bowl.

Plus, McGuire’s estimate of the trip’s cost is inflated. The influencers didn’t fly first class on Emirates, they flew business class, which costs around $5,500 per ticket based on a search I just did for a long weekend-length trip departing from New York around a month from now. As for the Ritz Carlton villas, the price of those are on the hotel’s website and, again for a long weekend around a month from now, would cost roughly $900 per night — and that’s assuming Tarte booked the most expensive kind of room.

The reaction to the trip was so strong that Tarte founder Maureen Kelly talked to Glossy about it to clear a few things up:

“Every day, brands make decisions about how to spend their marketing budgets. For some companies, that means a huge Super Bowl commercial or a multi-million-dollar contract with a famous athlete or celeb. We’ve never done traditional advertising, and instead we invest in building relationships and building up communities,” she said. Kelly declined to share Tarte’s total investment in the trip.

“I have to laugh at some of these conspiracies. I will say, people are creative! But no, I can confirm that we definitely didn’t have help from any tourism boards,” she said, in response to a theory stated in multiple TikToks.

She said that the brand didn’t pay the influencers or ask them to post about the trip, which was part of the launch for the brand’s Maracuja Juicy Glow Foundation and run in partnership with Sephora Middle East.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

A disbelief about Tarte’s success — which turned out to be widely held across the internet — underscores a lack of understanding of the beauty industry and influencer marketing. It also points to a misunderstanding of entrepreneurship and business more broadly, and likely also to a societal preference for valuing women for their looks above all else, as Barstool so often does. Why shouldn’t Kelly have been able to build a successful brand with credit cards and a dream? Why is it so hard to believe that she built a company — that people like McGuire might not know anything about but many others do — with enough of a marketing budget and team to pull off a trip like this?

That incredulousness mirrors a what seems to be a broadly held feeling about influencers. How can it be that these people get to enjoy these luxury experiences just for posting social media content? How can it be that influencing can be such a lucrative job, for young women in particular? How can it be that influencing is a job at all, and such a great one at that?

Though much criticism of the Tarte trip revolved around its excess during a time of economic uncertainty and hardship, it clearly wasn’t just this that provoked such a strong reaction. Displays of excess are all around us on the internet all the time. The predominant online sentiment about the couture shows that just walked in Paris, for instance, wasn’t that they were insensitive because people are struggling. The same goes for the continued existence of Vogue — and any number of other things.

For many years, news outlets have published entire articles about the gift bags Oscar presenters receive, which have included things like Tahitian pearl necklaces and luxury trips. The 2021 gift bag, including a three-day trip to a Swedish island and a liposuction procedure, was valued at $205,000. This was in the middle of the pandemic, a time of mass illness and death and, yes, economic hardship. Many would agree that the famous actors who receive said gift bags are among the last people who needed a handout. But an army of TikTokers never materialized to take them to task.

Sure, obvious differences exist between an Oscars gift bag and an influencer trip. Oscars presenters aren’t incentivized to post about the gifts to social media, so there’s not an onslaught of TikToks about them every year. But also, I suspect people are more comfortable with people who have a more traditional job (actor) enjoying material rewards for their work.

As far as the media has come since the Y2K heyday of Paris Hilton, there’s still a pretty broad discomfort with the idea of fame for fame’s sake, which I suspect is how influencing is perceived — a job that offers huge rewards to a select few who don’t really do anything. But, just as it was work for Hilton to show up to events and launch perfumes and walk in fashion shows and speak to the media, influencing is work. Making social media content requires, among other things, creativity, taste, a great eye, editorial skills, and proficiency with video editing. Getting brand deals requires the same kind of strategic thinking and glad-handing we congratulate businessmen for doing. It’s just that when women apply those skills to, say, a personal TikTok feed, they become somehow distrustful.

That attitude helps explain the feverish anticipation of Insider’s story about Arielle Charnas, one of the most successful Instagram influencers. She started in 2009 with a personal style blog called Something Navy, built up a following of 1.3 million on Instagram, and launched a clothing line. Before the Insider story came out, speculation circulated online that her husband was embezzling funds from her company and the couple were divorcing. Shortly after Something Navy CEO Matthew Scanlan shut those rumors down, the Insider story came out, detailing issues that are bad, don’t get me wrong, but probably also not particularly unique to this company. The story reported serious allegations, like that Something Navy was late paying suppliers and employees, but also minor things, like how Charnas “mispronounced the names of brands, including Vivrelle and the skincare brand Elemis, in videos, according to two former staffers (Elemis asked that Charnas reshoot the video).” It wasn’t a flattering piece, but it was hardly the bombshell downfall people seemed to be craving.

This isn’t to say the influencer industrial complex isn’t worthy of critique. I suspect the influencers who profit from this work the most possess many privileges that brand partners are happy to exploit. But relishing in their downfall or looking for a way to cause it carries the same uncomfortable pitchfork mentality as the media’s gleeful takedown of the “girlboss.” We’ve seen so many brands disappoint TikTokers in the last couple of years that Tarte, in my mind, aced this assignment. They got a bunch of influencers together, showed them a good time, and were rewarded with positive posts from them instead of complaints, which you most certainly couldn’t say of Revolve Fest. While it is crazy that being entertained on a luxury trip is a job for a select lucky few, this is simply marketing now — a 2023 version of a billboard that would have been impossible to imagine 30 years ago even in a dystopian future.

So, yeah, this shit is crazy, but don’t hate the player, hate the game.

Look at that, you made it to the end! You must have liked something here. Subscribe now if you haven’t yet to support independent fashion journalism and get Back Row delivered to your inbox around twice a week.

Amy! This is so good. The amped-up outrage has baffled me. Influencing is work (with a lot of privilege and some problems, as you note). But brands are choosing to spend the marketing budgets this way because there’s a real ROI here. It’s how people shop today, these accounts move product and these trips raise awareness about a launch — in a very quantifiable way. Be mad about that!

This is so true - remember all the stuff around WeWoreWhat!? Not saying Jr wasn’t shady but my god, the glee. Ditto Caroline Calloway (who lent - and still leans - into the grift, which I think is actually the answer.) Influencer culture is somehow way more scrutinized than other kinds of advertising - celebrities like Anya Taylor-Joy are the face of about 6 different luxury brands, probs millions of $ a pop, regularly Instagrams/ attends events, doesn’t always use an ‘ad’... but that’s way more offensive to ppl than an influencer going on an unpaid trip. Ditto magazines churning out advertorials, or their staff ‘picking’ products for their shopping pages that ‘just happen’ to be made by one of their luxury advertisers that season. Literally this kind of quid pro quo is everywhere in fashion publishing. Sponsorship and advertising is the foundation of celebrity culture/ retail - let’s at least appraise it with the wide-angle vision it deserves!