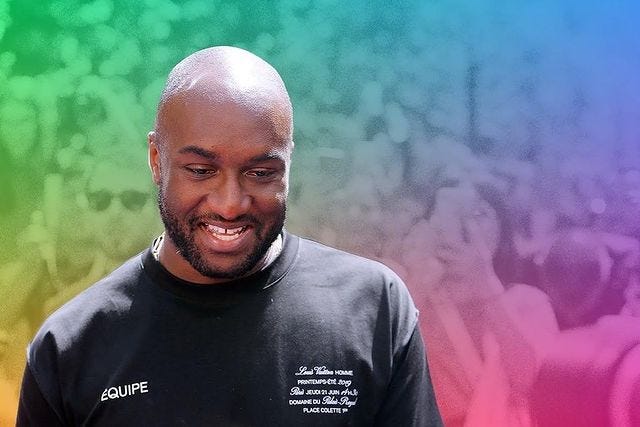

Despite Criticism, Virgil Abloh Soared

Recent tributes have papered over the industry's sometimes catty attitude toward a genius who changed fashion.

Four days before his death on Sunday, Virgil Abloh posted an Instagram teasing the show walking today in Miami of his spring 2022 Louis Vuitton men’s collection, featuring 10 additional looks. It’s one of countless reminders that the show should not be called, “Virgil was here.” Abloh, who was 41, a husband and father of two, should have not just been there, but also had decades more to work.

The world has been suddenly prompted to define Abloh’s legacy. Abloh was a remarkable mega-creative — a DJ, artist, and designer, though he preferred to call himself a “maker” — who ascended to the heights of the fashion industry. Without formal design training, he succeeded through talent, vision, stamina, hard work, kindness, openness, collaboration, and popularity. And he did it while rising above criticism along the way, including in his last years of life, while he was terminally ill and none of us knew because he was still working, making things people loved.

The media has been blanketed in his obituaries. Go read the brilliant Robin Givhan in the Washington Post. Or Matthew Schneier for The Cut. Or Luke Leitch for Vogue. Or Chantal Fernandez and Vikram Alexei Kansara for Business of Fashion. Or go read his old interviews — in New York magazine, the New York Times, GQ. I’ve been glued to my phone since Sunday, absorbing them all.

Abloh was born in Rockford, Illinois in 1980 to parents from Ghana. He studied civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then went on to earn a masters degree in architecture from the Illinois Institute of Technology. Fashion wasn’t something he studied, but he learned about making clothing from his mother, a seamstress.

This background was not exactly a template for climbing to the apex of high fashion success, making his rise all the more extraordinary. Designers for major houses are almost always white and very often have trained in classrooms in European capitals or New York in things like pattern cutting and tailoring. But Abloh’s talents weren’t the kind that you can learn in school. They were informed by study, but also his life and instinct. He has been credited in nearly every article published since his death with, as the New York Times put it, “bridging hypebeast culture and the luxury world,” or as Business of Fashion stated, “bringing streetwear to the highest levels of the luxury market.” So ubiquitous is that influence now, it’s almost impossible to imagine fashion today without it.

From the beginning, he fit no box. After he met Kanye West at age 22, he became his creative director of sorts, working on all kinds of projects from fashion to music, though the media never seemed to know what to call him. In a 2008 Guardian article, Luke Bainbridge wrote about West seating him in the front seat of the car for their interview while West sat in the back with Abloh, “a designer who is showing him images on a laptop.” In a 2010 article about West, Rolling Stone called him “West’s right-hand man.” Chicago magazine labeled him “Kanye West’s art director” and “style advisor” in 2011. And in 2012, the Times referred to him as West’s “close associate.” That, he most certainly was; W magazine reported that Abloh “once spent a month holed up at Tokyo’s Grand Hyatt with West in the aftermath of his mother’s death and the Taylor Swift debacle” at the 2009 VMAs.

That same year, Abloh and West interned at Fendi, where they unsuccessfully pitched leather jogging pants. Abloh also proposed to his girlfriend of a decade, Shannon Sundberg. The story of how he did it appeared in Inside Weddings:

Virgil decided to ask Shannon to drop him off at the airport for a work-related trip as she normally did; they said their goodbyes and Shannon routinely jumped out of the car to run over and take the driver’s seat. When she reached the other side of the vehicle, Virgil was waiting for her on one knee. “I was completely surprised – I couldn’t believe it!” remembers Shannon.

Abloh was always traveling, seeming to multitask to the extreme. While he was working for West, he owned RSVP Gallery, which Chicago magazine called “a lifestyle boutique,” and was a partner in the company @Superfun, which did events and branding. He told the magazine he was only in Chicago one week a quarter, “but I stay in tune because this is where I’m from.”

“My first influences were a cocktail of growing up in the Jordan era, [watching] hip-hop videos after school, and window-shopping on Michigan Avenue,” he continued. He said he loved the silhouette of a baseball jacket, but so few are made well. “I’ve worked full-time alongside Kanye West in the creative category for seven years," Abloh continued. "No one works harder for better art, design, and taste levels on a pop-culture scale than he does.”

Well, perhaps Abloh did.

On December 12, 2012 (12/12/12), he launched the clothing line Pyrex Vision, about which the Times blogged in 2013:

There had been some fuss recently over very expensive shirts by Virgil Abloh, who works with Kanye West and who designs a label called Pyrex Vision. He prints them on the back with a name and number, his being Pyrex 23. (Mr. West wore a hoodie during a performance to benefit victims of Hurricane Sandy.) The shirts are so expensive, and allegedly made from shirts that Mr. Abloh bought and then repurposed with a big markup, that he stands accused, and I am not making this up, of “swagger jacking.”

Items quickly sold out at upscale places like the Colette boutique in Paris. At the end of the year, Abloh started the label Off-White, described as “a high fashion take on streetwear,” telling Style.com, “Streetwear has a one-trick-ponyness to it,” adding, “I want to give my point of view and merge street sensibilities in a proper fashion context. I think that if I can merge the two, it'll make something interesting.”

His idea was to take items he loved that reminded him of his youth, like T-shirts, and manufacture them in the same factories used by luxury brands. He said his inspirations for that first collection were "Montauk and Martha Stewart and Nantucket.” After putting out his men’s collection, women’s wear followed the next month, Abloh’s name now increasingly the headline instead of just West’s. Women’s Wear Daily reported that Abloh wanted “to eventually build Off-White into a lifestyle brand comprising clothing, home goods, luggage and more.” That first women’s collection was called “I Only Smoke When I Drink.” The line’s signature became phrases written in quotes on clothing, like “little black dress” printed on a little black dress or “shirt” printed on a shirt.

The media then became fascinated by streetwear’s influence on high fashion, and Abloh started getting a lot more attention as his line’s popularity began to explode. Rebecca Gonsalves wrote in a 2014 Independent profile, “One way in which Abloh's designs differentiate significantly from the established ideals of the style is his distressed aesthetic — fabric is ripped and frayed, subverting the usual prestige of keeping an item box-fresh.”

He also described himself as a “compulsive collaborator.” He was known for finding artists on Instagram and forging partnerships with them. And he spoke of the “three percent approach,” which was that design success came from changing an original item just that much. And in that Independent story, he expressed immense admiration for Raf Simons:

"I would be an intern — sweep the floor, clean his living room — just to be in that space. He's such an inspiration, but I wouldn't collaborate because I don't think I'm worthy," he says.

Abloh was fixated on his roots, but also young people (the “post-Tumblr generation” as he once brilliantly put it). They were going into stores they wouldn’t have otherwise just to buy Off-White, the Times reported. Business of Fashion reported that Off-White “quickly surpassed $100 million in revenue.” For a young high fashion label selling $1,000 sweatshirts, that success isn’t just unusual — it’s insane.

The fashion industry itself seemed to embrace him at first. He was a finalist for the 2015 LVMH prize for young designers. But one also got the sense that some in the establishment didn’t like him coming in and changing their rules and the public’s idea of luxury.

In a 2017 GQ interview, his inspiration Raf Simons was asked if he felt inspired by young designers like Abloh. Simons said, “He’s a sweet guy. I like him a lot actually. But I’m inspired by people who bring something that I think has not been seen, that is original.”

Abloh worked famously hard — seemingly impossibly so — but maybe he did it because, for him, there was no other way. He collaborated furiously — with Nike, Ikea, McDonald’s, Evian, Equinox, Jimmy Choo — throughout his career. In 2018, Time magazine named him one of the most influential people of the year. Then Louis Vuitton hired him as artistic director of menswear, and he sent his debut collection down a rainbow runway before an audience including West, Rihanna, and 1,500 students. (Despite his work commitments, Abloh was dedicated to lifting up the next generation of designers; in 2020, he raised $1 million to start the “Post-Modern” Scholarship Fund for Black Students.)

But this is fashion. It’s a catty business. When people reach the top, the attacks come. And Abloh was charting not only a new approach to luxury but also doing it as a Black man, entering ranks where virtually none of his peers had ever looked like him.

Around the peak of his success, he dealt with copycat accusations. Many in the industry saw these callouts on Diet Prada, which Business of Fashion aptly calls, “the most feared Instagram feed in fashion.” When Abloh collaborated with Ikea in 2018, Diet Prada wrote that one chair was “actually an icon of mid-century design by Paul McCobb for his Planner Group series.” Later in 2018, they posted that he “rip[ped] off a famed graphic designer [A.G. Fronzoni]’s work” for a T-shirt. In January of 2019, they pointed out similarities between a look by Off-White and the lesser known label Colrs.

In a great 2019 New Yorker profile by Doreen St. Félix, Abloh responded to the accusations:

When I mentioned the [Colrs] post to him, he took the opportunity to praise Diet Prada’s editorial project. “All props to them, that’s a great concept,” he said. But he added that the account didn’t take into consideration that coincidences can happen.

He said that he had never seen the Colrs look when he designed his yellow ensemble. The allegation was founded on “basically the use of a yellow fabric with a pattern on it,” he said. “Ring the alarm!” He sighed. “I could go on for a whole hour about the human condition and the magnet that is negativity. That’s why the world is actually like it is. That’s why good doesn’t prevail, because there’s more negative energy. You can create more connective tissue around the idea that this is plagiarized. It’s better just to sit and point your finger. That’s what social media can be. All that space to comment breeds a tendency to fester, versus actually making something.” He went on, “It allows you to package up this thing as: ‘You’re not a designer. Close the book. Because, designers, you should be from Belgium.’ ”

Fashion people are terrified of appearing on Diet Prada (which posted a tribute after Abloh’s death was announced). Yet it happened to Abloh, he defended himself, and his success continued. Designer Walter Van Beirendonck later accused him of copying his work; Abloh defended himself once more. Abloh’s approach to design was thoughtfully considered by Rachel Tashjian in a September 2021 GQ article that I recommend reading in full:

More recently, Abloh has expanded his thinking on copying to embrace concepts from DJ culture, which constructs something new from pieces of other artists’ work. His ever-expanding show notes for Louis Vuitton this past July included a number of riffs and essays about sampling; the collection was called “Amen Break,” after one of DJ culture’s most commonly sampled drum breaks. One piece, a letter to “Dear Fashion People,” noted that the Amen Break has been sampled over 4,000 times, and that “the Louis Vuitton Spring-Summer 2022 Men’s Collection follows this logic of sampling the readymade to make new things from the old. Men’s Artistic Director Virgil Abloh understands how much of today’s culture has been about stretching that initial six seconds into an infinite loop.” It concluded, “Abloh’s praxis is crate-digging through the canon to find the B-sides and rarities that mustn’t be forgotten. He juxtaposes references in the same way a DJ beat matches two disparate tracks—you find the mutual point where the vibe lines up and switch it up from there, an act of coordination that takes painstaking practice to look absolutely effortless.”

When critics and commentators complain and complain and the creator doesn’t change, but instead doubles down, we have to ask: is it we who are missing the point? Knocking off isn’t a naughty habit of Abloh’s; it’s the entire purpose of his work.

Then in 2019, not long after he got the Louis Vuitton job, he was diagnosed with cardiac angiosarcoma, a rare heart cancer, and decided to keep his illness private.

In February of 2020, the New York Times wondered, “Is Virgil Abloh the Karl Lagerfeld for Millennials?” Subtitle: “Many in fashion are horrified by the idea. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong.” From the piece:

Almost every time I suggested it to someone while chatting catwalk-side during the most recent show season, which since early February has been moving from New York to London to Milan and now Paris, they blanched and said, “Oh, please, no!” or “That’s crazy!” or “Is this a joke?”

The story went on to say:

Mr. Abloh is the man who told the world (at Columbia), “You don’t have to be a designer to be a designer.” He doesn’t even call himself a designer; he calls himself a “maker,” according to The New Yorker — perhaps in acknowledgment of critics, myself included, who don’t think he is particularly great at his day job (or that he even cares).

But Lagerfeld did many of the things for which people seemed to knock Abloh. He drew inspiration from existing designs. He collaborated with Coke and H&M and Magnum ice cream. I once sat in a room where fashion people at the very top of the business admitted they didn’t even think his stuff was all that cute! He was perhaps more stylist than designer. But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t brilliant. The same goes for Abloh. He changed fashion through a vision no one else had and an unbelievable amount of hard work. Basing success and talent purely on classic couture bona fides in 2021, when the digital world drives both culture and purchases, is ridiculous and illogical.

After his death, the fashion internet seemed to have forgotten all the criticism it lobbed at Abloh. One got the sense, scrolling Instagram, that a subsection of the industry was actually trolling their DMs and photo libraries looking for any interaction they may have had with him to share in the wake of his terribly shocking, terribly sad death. (Abloh did embrace social media so perhaps he would have been fine with users constructing a posthumous image of him through these arguably opportunistic dribs and drabs.)

In a post to his Instagram account Sunday, Abloh was remembered as often saying, “Everything I do is for the 17-year-old version of myself.” The demands on his time and the criticism he dealt with would be incredibly difficult if not impossible for most people to handle. That Abloh kept creating — or making, as he might say — through it all, even receiving a promotion at LVMH last year that gave him, WWD reported, “leeway to launch brands and seal partnerships across the full range of the luxury conglomerate’s activities, beyond just the fashion division,” speaks to his strength of character. His death is a huge loss for the industry and the untold number of young people who looked up to him and will one day walk the path he forged.

Subscribe to Back Row to get more posts like this sent straight to your inbox.

Great read thank you

You're so right, the fashion industry has a notoriously short term memory and sometimes isn't very honest about things done and said. I'll be honest, I didn't always get it. As a matter of fact, I wrote that in a post about his shocking passing. But even though I didn't get it, didn't mean I never thought for a second that his contributions weren't important. That seems to be what people constantly don't get. Just because you might not understand it or maybe it's just not for you ... doesn't mean it doesn't lack in importance. Sometimes it's you that's just not seeing it (I always weigh this thought because sometimes we're just late to the party). I was always happy to see Abloh making moves in the world even if I will NEVER wear the cool kid sneakers. I often think that some of his more negative reviews came from his connection to West who definitely became more of a contentious character in recent years. And that's a bummer too.