Discover more from Back Row

Alo Yoga Became a Behemoth by Claiming to Be Something It's Not

"We don’t do things for money. A lot of businesses do, they are just for-profit. That is not us at all," said Alo's cofounder. He bought a $30 million house in 2017.

Thank you for subscribing to Back Row. This issue is free to read, however this newsletter is made possible by paying subscribers. If you like these stories and believe in a reader-supported model for fashion media, which means Back Row is beholden to YOU instead of advertisers and brands, I hope you consider upgrading to a paid subscription for $5 a month (the price of a coffee in a city) or $50 a year. Paid subscribers get two stories a week, plus bonus fashion month recaps.

We’re in a horrifying cultural moment where brand podcasts are like the celebrity skincare line of content: as abundant and solipsistic as they are useless. The one thing you can say in favor of brand podcasts over celebrity skincare is that at least the podcasts are free? Whereas if you want to buy Brad Pitt’s new “The Serum” from his “genderless” Le Demaine skincare line, you have to pay $385.

On Saturday, September 17, I got an email from Alo Yoga with the subject, “Alo’s NEW PODCAST is Here!” I’m on the email list because I’ve bought a couple of things from their site, and I have liked their clothes for working out and sitting around my house. The podcast is called Mind Full, and if you think you’re going to escape this newsletter without the word “clean” coming up a few times, I have bad news for you.

The first guest was Ye, who spoke to host Alyson Wilson and Alo cofounder Danny Harris. This is one of those podcasts that was videotaped, so I can tell you that Harris was wearing a skintight black T-shirt, perhaps in a sweat-wicking fabric, and a black Alo hat. Ye wore a frayed baseball hat that cast a shadow over his face, enhancing the mythology surrounding his celebrity that makes people think it’s a stroke of creative genius for him to give this much time to an internet athleisure brand’s podcast. However, I’m less convinced it’s that than him sticking it to the Gap, which just ended its partnership with Ye and which also competes with Alo.

Here’s a transcript of a portion of the show:

Danny Harris: …For him [Ye], you know, to take the time out and come down and see what we’re doing, and then him telling me that our manufacturing and our excellence and our efficiencies were inspiring him? I mean, what a compliment. And we were trying to define, like, how would we call this excellence? What would it be? And we established that this is the Ye of manufacturing.

Alyson Wilson: Oh sick. Love that.

Ye: That’s the highest compliment. I mean, under God is for me to say it’s the Ye version because only God can have the God version. But right underneath that is the Ye version.

Harris: [laughs]

Wilson: So good.

The episode proceeds much like this. It is annoyingly short on specifics. Harris describes reading a certain book a hundred times, noting that Ye hasn’t read the book. Ye says, “I actually haven't read any book.” But neither of them says what the book is. Why? Because Harris is afraid we’ll buy the book instead of $118 leggings?

Ye is a prolific creative and brand builder, a cultural force. This is not to say he’s perfect, but there’s a reason the video of this podcast has more than 430,000 views at the time of this writing. I can only imagine the glee over its performance in the Alo marketing department. At the end of the episode, Ye says, “I honestly believe that Gap and Adidas are part of a bigger plan to marginalize American companies and American industry, which is the opposite of what Danny’s doing, and that’s why you see this glow coming from me.”

However, the podcast also offers no specifics on why Ye believes this and what makes Alo’s manufacturing so terrific. I pulled out a pair of Alo sweatpants and shorts I own to see what the labels said. Alo is fully vertically integrated, meaning it owns all its manufacturing facilities, and advertises itself as “100% sweatshop free.” As if to confuse customers, the labels on my items read, “Designed in Los Angeles Made in China” and “Designed in Los Angeles Made in Vietnam.” Partly because so little information is provided on Alo’s manufacturing process, the site Good on You that rates brand ethics gives Alo a “We Avoid” rating. After researching the company a bit, it seems to me that it is a highly effective one that profits because it doesn’t burden itself with living up to its professed values.

Harris and his co-CEO Marco DeGeorge started Color Image Apparel in 1992 in Los Angeles. Alo started under Color Image Apparel in 2007. (Also in the Color Image Apparel portfolio are T-shirt company Bella + Canvas and maternity line Ingrid + Isabel.) Alo stands for “Air, Land, and Ocean,” and the brand claims its goals include “bringing yoga to the world” and “[t]aking the consciousness from practice on the mat and putting it into the practice of life.”

If Harris and DeGeorge had an instinct in 2007 that a yoga- and “wellness”-oriented brand headquartered in Los Angeles could be extremely profitable, they were obviously onto something. Gwyneth Paltrow didn’t start GOOP until 2008. Both brands were at the forefront of today’s pervasive “wellness” culture, which pressures women in particular into spending a large percentage of our time worrying about things like mental clarity, disconnecting from technology, “clean” diets, skincare, and working out. That’s not to say that all of these things are bad — disconnecting from technology and exercising have proven health benefits — but it’s also true that the wellness industrial complex markets them as expensive aspirations.

In the case of Alo, the promise was that we could wear the clothes whether we were doing yoga or not, which at least would make us look like one of the people who cared about self-improvement via goji berries and meditation, even if we didn’t have the time and disposable income to devote to those things. If you are like me, you found Alo (or Alo found you) online. The brand started around three years before Instagram, and figured out sooner than many fashion companies how to use influencers and celebrities effectively in social media marketing. One revealing piece of information in the podcast on how the brand has become so ubiquitous comes from Ye, who mentions “that triangle you [Harris] drew out this morning that goes from influencer to more influencers to early adopters to audience to critical mass.”

Alo has reached critical mass — and then some.

Harris says on the podcast, “We don’t do things for money. A lot of businesses do, they are just for-profit. That is not us at all.” Yet Alo, which is a for-profit company, has certainly made Harris a lot of money. In 2017, he purchased a home in L.A.’s Holmby Hills neighborhood for $30 million from Bebe clothing founder Manny Mashouf. The house is more than 20,000 square feet, occupies 1.21 acres, includes eight bedrooms and 11 bathrooms, and has a tennis court and a pool. A Dirt.com article about the home noted that Harris would have had to sell 566,038 pairs of its cheapest leggings (which cost $53 then) to buy the house.

And that was just 2017. Back then, the company was still becoming an octopus with tentacles in so many business ventures that it would become hard to even keep track of them all.

Alo got in early on things that would only enable it to reap huge profits during the pandemic, when so many businesses and people suffered. Not only was Alo cornering the market on cool-looking athleisure, but they were also getting into content. Harris told Forbes in February 2020, “The future is in content.”

In 2018, Alo acquired the yoga app Cody, renamed it Alo Moves, and started selling subscriptions for customers to stream yoga and meditation videos. The acquisition led Alo to sue body positive influencer Dana Falsetti after she disclosed the still-confidential merger in an Instagram story and accused the brand of “perpetuat[ing] body shame.” Yoga Journal reported that she was driven by concern over being aligned with Alo, which her students and fans viewed as “antagonistic to her advocacy for the health and wellness of large-bodied persons.”

This seems to have been the biggest public falling out that Alo had with the online yoga community from which it was profiting. Some yoga instructors rushed to Falsetti’s side; others hired by Cody who continued appearing on the new Alo Moves were maligned for associating with Alo. An impassioned debate emerged on yoga social media about yoga’s values and how they could be at odds with for-profit companies.

Kino MacGregor, a yoga influencer and Cody instructor who defended Falsetti, wrote in a blog post:

Hold every yoga teacher and yoga influencer accountable for what products and companies they endorse. Hold every company accountable for their actions. Stand your ground. Vote with your dollars and your attention.Be discerning. Look for the hidden signs. Some social media accounts named for “yogainspiration” or “yogagoals” or “yogachannel” are actually subliminal marketing run by large corporations. They don’t tell you it’s a company page, but if you notice that all the yogis are wearing the same brand, you can bet that it’s a corporate account…

Turned out these accounts — @yogainspiration, @yogagoals, and @yogachannel — were all owned by Alo, which was a smart marketing move. However, that wasn’t being disclosed at the time, according to Yoga Journal. (Now the accounts clearly disclose in their bios that they are “by Alo.”) MacGregor’s blog post earned her a cease-and-desist letter for, an Alo spokesperson said at the time, “violat[ing] the terms of her contract with Cody.”

Falsetti came to terms with Alo, and posted a public statement about how she “failed to completely understand a contract that I signed, and that is my own fault.” As social media flare-ups always do, this one died down. And by early 2020, with retail on the precipice of a pandemic-induced battering, Alo had six brick-and-mortar locations. By the end of 2021, it had 13. Some stores included yoga studios (a single class at New York’s Soho location costs $32).

In early 2020, Harris told Forbes that revenue was around $200 million, with the brand bringing in around $40 million between Black Friday and Cyber Monday in 2019 alone. In March of 2021, Fast Company reported that Alo’s revenue grew by 150 percent in 2020, which would put it at $500 million. The driver of that growth was the pandemic — a period of illness instead of wellness — when consumers doubled down on at-home fitness and loungewear, all things Alo had been doing for a while.

Having already gotten into clothes, streaming videos, and brick-and-mortar retail, what else was left for Alo? The children, apparently. Alo Gives launched a few years ago with the goal of bringing yoga to kids; the website offers free yoga videos to show your young children.

Yet Harris said on the podcast, “We’ve talked about kids on iPads at 2 years old and with, you know, cell phones and social media and video games and all of these ways we need to give people an outlet on how to deal with their minds.” He added, “We were on a wonderful trajectory of bringing our curriculum into schools before, you know, Covid, when breath work became a negative thing. But one day, I look forward to getting right back on that path.” As with Alo’s manufacturing, how they plan to infiltrate schools is not specified.

However, putting this past them would be foolish given every other category the company has infiltrated. In late 2020 came an Alo restaurant, Sutra, on the roof of its four-story 13,000-square-foot Manhattan store in the Flatiron District. (The “clean” dishes served included “three beet poke with crispy rice, pineapple adobo tacos and golden milk coconut cream pie with spiced cashew.”) Shortly after that came Alo skincare, “a botanical-powered range of clean, self-care products.”

The brand also does events. It opened a giant Miami store last year with “a three-day party,” WWD reported, featuring influencer VIPs. As a top-billed fashion week sponsor, it set up a hub at Spring Studios offering “sound baths,” kundalini yoga, “intuitive readings,” and “acupressure ear seeding,” with “gems, crystals, and sage bundles decorating every corner.” It also presented its new Aspen Collection, which is higher-end winter Alo stuff (cashmere pants!), from which the brand derived its first NFTs. If sponsoring fashion week is about a goal other than making money – i.e. getting the fashion world to take it seriously to justify the higher prices – what is it? Offering sound baths to fashion people? This past spring, Harris bought another house, this one for $14.25 million in Malibu.

Alo is a brilliant business, one that seems explicitly designed to dominate the athleisure market and make its founders a lot of money, despite Harris claiming otherwise. It’s not hard to see how Ye and many others might admire it from a business perspective.

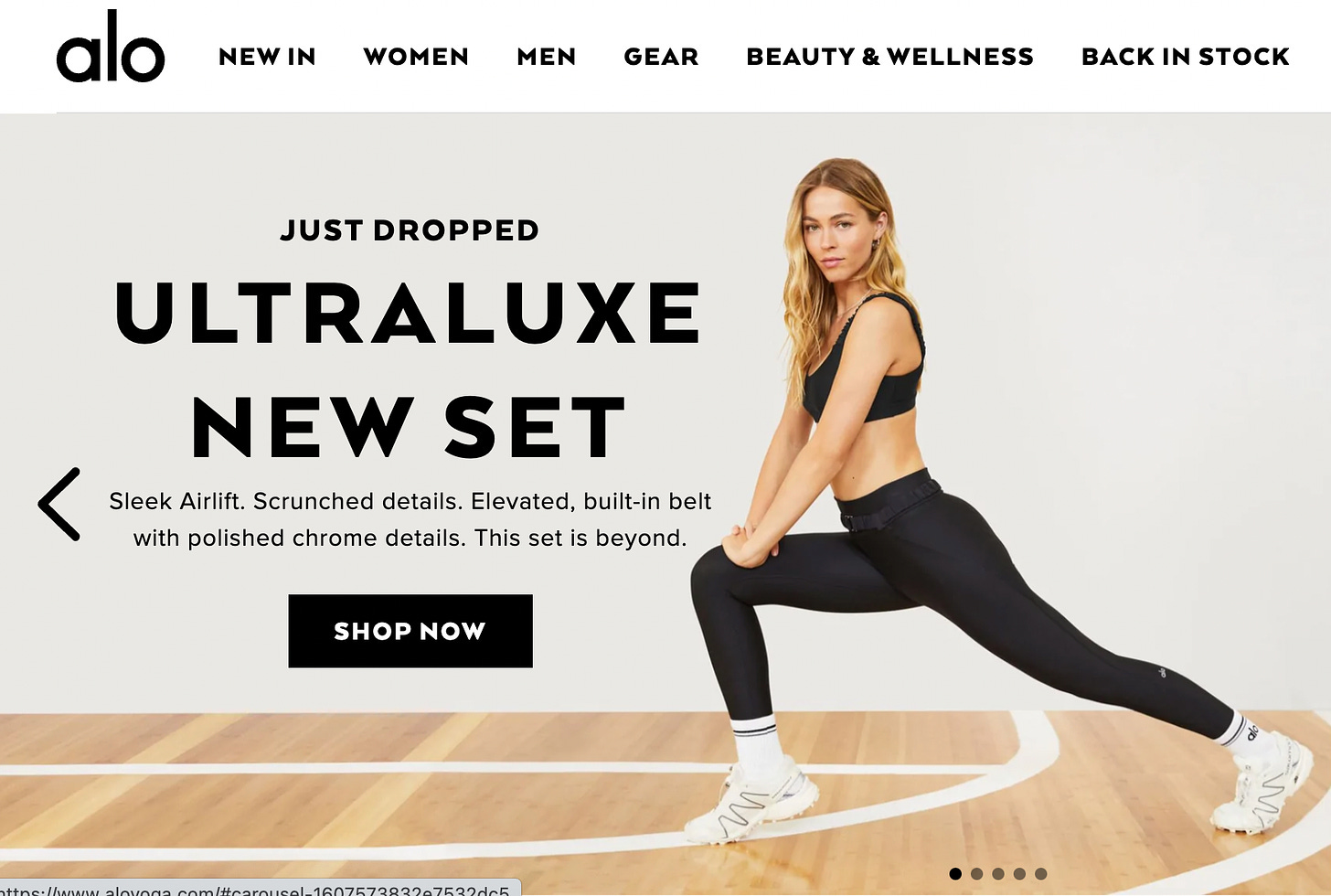

Yet one of the most impressive aspects of the business is how Alo subversively creates the online culture from which it purports to want to help its customers escape. It markets on Instagram, an addiction many of us would like to dispense with, with images of mostly thin, young women. It did this not just by hiring influencers and having its own popular account, but also by taking on other accounts that once purported to simply be about yoga instead of marketing Alo. It also took and threatened legal action against yoga instructors, sending a clear message to others in the yoga community who cross them. And it offers streaming content — which is designed to be addictive and, to use Alo speak, mind-clouding — for adults and children.

Alo is well within its rights to do all of this. This is how effective, behemoth, for-profit companies operate. It is also well within its rights to try to become a media company with endless content extensions — tentacles on tentacles — like podcasts that help spread its hypocritical gospel. With journalism and media in the state they’re in, a company like Alo is going to have the resources to create and market celebrity interviews and podcasts that a dusty old media company will not.

This was so interesting, Amy. And kind of speaks to something that is (in my opinion) so central to American society -- that everything in this country these days feels kind of like a scam, more or less.

I'm not saying Alo is literally a scam, but at the very least they are masquerading as some kind of enlightened entity when, at its root, it was perhaps created—partly—so that the founder could buy a $30 million house. I think you could say similar things with regards to, say, Goop, a company that very much blurs the line between "authentic" content and sponsored content (almost all of their travel content, for instance, is sponsored now, and "partners" aka advertisers can basically dictate what's included in an article). And while I do believe that GP has good intentions...I also believe she wants to become a billionaire via her company.

Imagine how thrilled Alo Yoga must be with the news of Ye's (just under God?) antisemitc tantrums. Such a great reflection on them.